The Air Force of the Polish Army

(Lotnictwo Wojska Polskiego)

Polish Air Force of the Polish People’s Republic

Introduction:

The Sikorski-Majski pact that had been signed on 30th July 1941 in London, changed the living conditions for the interned Polish forces by the Soviets. While many Poles left internment camps and the gulags for the Middle East (about 80,000) to join Anders Army, those who chose to stay or were left behind were incorporated into a Polish Army based on an agreement between the communist leaders of Poland and the Soviet Union on 14th August 1941 (Cynk, 1972; Krzemiński, 1983; Cynk, 1998). It was designed by Stalin not to provoke a threat to his post-war plans for central and eastern Europe through Soviet indoctrination that was not always successful. The 1st Kościuszko Infantry Division was the first unit to be created under the command of Col. Zygmunt Berling at Sielce about 80 km south-east of Moscow (Link: Polish People’s Army) in May 1943. As recruitment and training in Soviet style military methods and command structures developed, the 1st Polish Army (Pierwsza Armia Wojska Polskiego) was created with the remit to develop its own air force to support Polish units fighting on the Eastern Front (Krzemiński, 1983; Rapiński, 2018).

The formation of a Soviet backed army and air force presented several difficulties. The captured equipment during the partition of Poland in the autumn of 1939 was close to obsolete and the interned troops were not familiar with Soviet equipment, tactics or command and organisational structures. Added to this fact was that those surviving interment in appalling conditions in the labour camps and gulags were some 475,000 out of the 1.5m-1.6m who had been deported. Polish officers massacred in Katyń (Link: Katyn Massacre) was not discovered until 1943 but the suspicions had been raised in December 1941 during Sikorski’s meetings with Stalin to settle the conditions for the Sikorski-Majski pact.

The training airfield at Grigoryevskoye just south of Moscow used Soviet instructors to train pilots from elementary to combat stages (Krzemiński, 1983) as the 1st Fighter Regiment Warszawa became operational on 6th October 1943 and commanded by Capt. Wacław Kozłowski (Cynk, 1972). The squadron consisted of 5 officers and 12 NCOs with a further 26 ground crew to attend to five UT-2 trainers and 10 Yak-1b planes which were close to obsolete and no match for the Luftwaffe’s Me-109D or Me-110C on the Eastern Front (Krzemiński, 1983). The airfield lacked proper facilities or accommodation for the squadron. Soviet Air Force Operational Theory had its roots in the old Imperial army prior to 1917 and had developed a more integrated role that focussed on manoeuvrability from the experiences of the Russian civil war. The subsequent development of Soviet tactical and operational practices was based on supporting front-line troops as an integrated unit in World War II. Typically, Soviet Air Armies would consist of fighter, bomber, assault, and mixed divisions to support the Front while an Air Defence Force made up of interceptors protected the civilian and military districts behind the frontlines. This is a significant difference to how both Britain and the USA’s tactical and operational command structures developed during the war (Garthoff, 1958; Drane, 1976; Krzemiński, 1983).

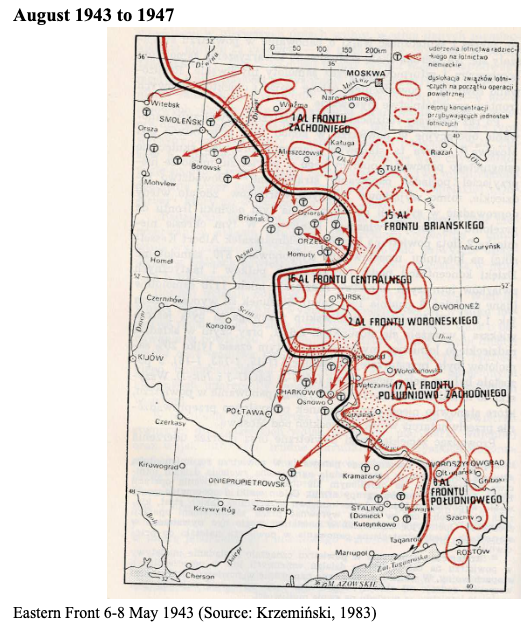

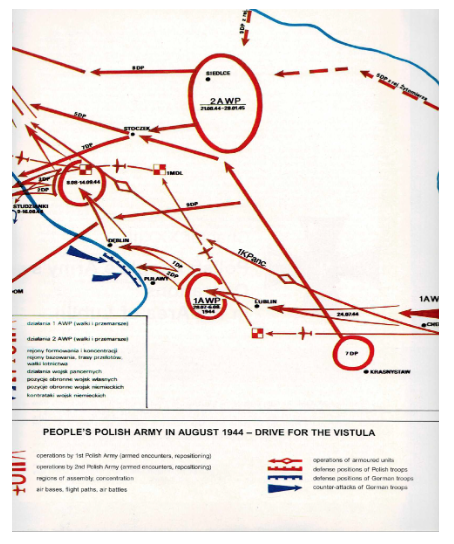

The map shows the Soviet attacks on key Luftwaffe bases within the zone of the main frontline prior to operation BAGRATION and the air combat zones supporting the Polish Army’s bridgeheads with rear reinforcements of Soviet Air Army combat divisions.

**********

The training regime was based on Soviet operational theory which meant that after 150 flights on a UT-2, trainee pilots would progress to the two-seat Yak 7U and then a single seat Yak-1b fighter for a further 100 flights completed in 25 hours with combat proficiency completed in 350 flights and a further 100 flying hours. It meant the Polish pilot trainees were completing their courses in half the time of their Soviet counterparts. By comparison, British Spitfire pilots took between 18 months and 2 years to complete their training that was around 200-320 flying hours although at the outbreak of war and during the Battle of Britain, some pilots had only 150 flying hours.

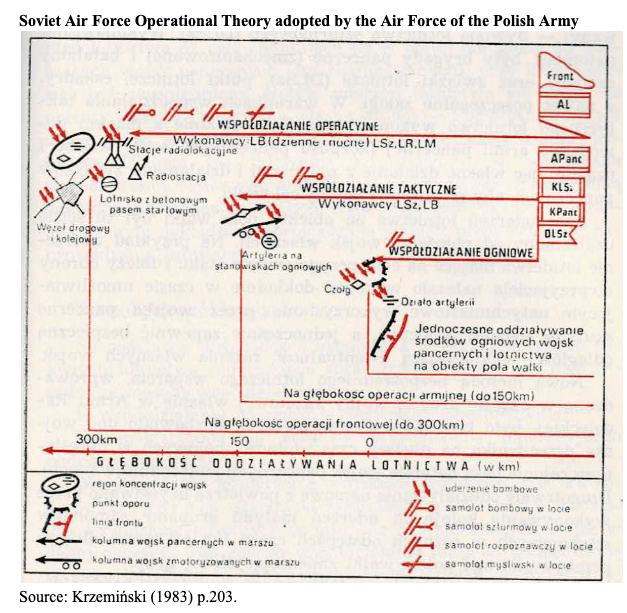

The above diagram outlines the typical framework for operations conducted by the Soviets and ‘recommended’ to the Polish Army and Air Force. It shows the tactics used within the immediate front lines (fire support to ground troops and targeting tanks), 150km (tactical support targeting artillery), and 300km (day and night bombing of radio communications and reinforced airfields).

**********

The commanding officer, Capt. Wacław Kozłowski was tragically killed with a Soviet instructor Senior Lt. Anatoliy Korovin on 10th August 1943 at Sielce (Cynk, 1972; Krzemiński, 1983; Cynk, 1998). Lt. Tadeusz Wicherkiewicz took over command on 16th August 1943 who unfortunately had limited flying and command experience but was still promoted to Captain.

In the second half of 1943 after scouring the Soviet Union for suitable recruits, the squadron was upgraded to a Polish air regiment (Cynk, 1972; Krzemiński, 1983; Cynk, 1998). The unit now consisted of 175 personnel of which 33 were officers. They had at their disposal 33 Yakovlev Yak-1 fighters and a Polikarpov PO-2 liaison biplane used for training and observation flights (Cynk, 1972; Krzemiński, 1983; Cynk, 1998). By the end of August 1943, a second group of Polish volunteers entered the flight training programme that required more UT-2s to be delivered to Grigoryevskoye so that by October 1943 the air regiment strength was 114 personnel of which 33 were officers. Some administrative roles were completed by women of Polish origins. On 16th November the first group of trainees were ready for combat duties and on 1st January 1944 the 1st Warsaw Fighter Regiment received its colours with aircraft sporting the ‘chequerboard’ on their planes, but it was not until 28th May 1944 they would be declared combat ready.

The Spring thaw forced the regiment to move to the Kubinka air base near Moscow and then Volosovo (Sumsk) in the Leningrad Oblast. In the middle of May 1944, the second group of trainee pilots graduated and joined the regiment. At the beginning of 1944, Soviet forces had advanced into former and disputed territories of Poland giving the Soviets ‘recruitment’ opportunities (Link: Polish People’s Army) to bolster the Polish army and its air force which could now be at divisional strength. However, amongst the local populous, the lack of any remaining aviators was too optimistic that set back recruitment targets (Cynk, 1972) resulting in the air assault regiment being temporarily abandoned. The recruitment and training programmes did enable the formation of the 2nd Night Bomber Regiment (Kraków) and the 103rd Independent Liaison Squadron to be operational on 1st April 1944. The night bomber regiments were equipped with light Polikarpov Po-2 biplanes that were fundamentally obsolete and based on a design from the 1920s with production being completed as late as in 1952. Due to shortages of crew, many planes were flown by Soviet personnel.

In early June 1944, the 1st Warsaw Fighter Regiment and 2nd Kraków Air Regiments were transferred to Hostomel, just south of Kiev with the 103rd Independent Liaison Squadron moved to Zhitomyr, an important transport hub to support the 1st Polish People’s Army. Towards the end of July 1944, a further 600 recruits were in the initial stages of a training programme at Soviet aviation schools based at Buguruslan and Serochinsk, well away from the frontline with only 468 completing their training (Cynk, 1972). The 40% failure rate lies with ability to recruit, candidates’ level of education and the number of those who had been deported or killed. A significant number of able-bodied men were fighting from the forests for the AK or other partisan groups in the former Polish territories covering the western Ukraine (Kresy) and Belorussia, some of whom were supported by the Soviets or sympathetic the AK Kochanski, 2012).

Operation BAGRATION between 23rd June and 19th August 1944 saw the 1st Polish Army being supported by the 1st Warsaw Fighter Regiment and the 2nd Kraków Air Regiment from 28th July 1944 under the command of 2nd Col. Alojzy Buczyński. Operation BAGRATION was launched and timed to coincide with D-Day invasion of Normandy. Army Group Centre attacked Belorussia and broke the Wehrmacht’s ability to effectively fight two major fronts consecutively with over 450,000 German casualties and another 300,000 trapped in the Courland Pocket. The loss of the German 4th Army and most of the Third Panzer and Nineth Army, enabled the Soviets to encircle the Germans in the area around Minsk. Once Minsk fell on 4th July, Poland, Lithuania, and further south Romania were invaded over the summer of 1944. Advance parties of the Polish People’s Air Force landed at the Dys airfield between Niemce and Lublin on 16th-17th August 1944 and one of the first Polish fighting units to return to Poland. This also marked the completion of the 1st Polish Composite Air Division with reinforcements of personnel and equipment from Hostomel and placed at the disposal of the Polish Armed Forces. Accompanying them the Soviet 611th Assault Regiment that was ordered to a forward operating base at Stare Zadybie south of Żalechów and to the north-west of Lublin (Rapiński, 2018).

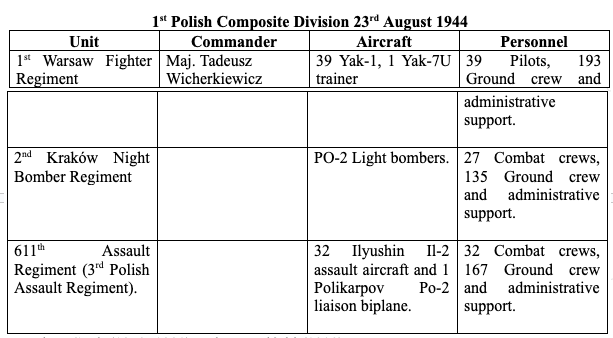

The first combat missions from Polish airfields commenced on 23rd August 1944 (Cynk, 1972; Rapiński, 2018). On 30th August 1944, the 1st Polish Composite Division was formally brought into existence comprising of the 1st Warsaw Fighter Regiment, 2nd Kraków Night Bomber Regiment and the 611th Assault Regiment that was renamed 3rd Polish Assault Regiment shortly afterwards. Under the overall control of Gen. Zygmunt Berling, Commander of the 1st Polish Army the unit suffered from personnel shortages at all levels with Soviets still controlling the strategic development of Polish forces (Cynk, 1998) and the suspicion of loyalty by the local populus to the AK undermining the Lublin Committee’s legitimacy (Kochanski, 2012).

Rebuilding of the Polish armed forces began in earnest through the forced integration of Soviet backed partisan units and any suitable locals. Members of the AK were openly hostile with local skirmishes and imprisonment with daring prison breaks from the NKVD camps while at the same time committing attacks on the retreating German units. The implementation of operation BURZA (Link: Warsaw Rising) deepened the Soviet’s attitude towards the AK and the Lublin Committee felt exposed unless the NKVD suppressed any resistance to Sovietisation. Although the Soviets were keen to rebuild the military economy and recruit troops and train pilots, the war and subsequent ‘scorched earth’ by the retreating Wehrmacht and the degree of frontline damage meant most of the infrastructure was destroyed with little to salvage. In turn, this created a strain on skilled personnel to fill the gaps and an Air Force operating redundant equipment, yet despite this, Col. Józef Smaga proposed the future of Poland’s armed services would include seven air divisions including a naval wing that would be implemented by July 1945. This ambitious plan would be completed in an unrealistic period of two years (Cynk, 1998). In late August 1944, Smaga was probably demoted when he became commandant of the Zamość United Aviation School until April 1945 when he was then made commandant of the Dęblin Military Pilot School. It is possible his ambitious plan and Gen. Berling’s failed role in the Warsaw Rising, challenged the leadership skills of the communist armed services where the continued loyalty to the AK still posed a great threat (Ciechanowski, 1974; Kochanski, 2012). The Lublin Committee became more reliant on the NKVD and established citizen’s militias to enforce terror (Kochanski, 2012) that would also undermine the Polish armed services training and recruitment plans.

Operationally, the airfields at Łowicz, Sochaczew, Łodz and Kutno were under the control of the 1st Polish Composite Division from February 1945 with training schools at Kharkiv and Kazan providing trained personnel to replace Soviets seconded to the Division. In late August to early September, the 103rd Independent Liaison Aviation Squadron was fully operational and working to support the 1st Polish Army with a newly formed 3rd Squadron supporting the newly created 2nd Polish Army. Personnel remained in short supply with infill by the Soviets being unpopular with both the Poles and Russians (Cynk, 1998). Its independence was limited by being incorporated into the Soviet 611th Regiment due to Soviet mistrust of recruits (Cynk, 1998).

Based on Cynk (1972, 1998) and Krzemiński (1983).

Yak-1

Col. Józef Smaga’s proposals were partially revived under Gen. Michal Rola-Zymierski that needed to be fully operational by 1st January 1945 with seven air regiments to be ready by 1st July 1945. To achieve this goal, the air training facility at Dęblin would need a massive injection of resources and construction improvements to cope with the change in capacity. By October 1944, the Soviet 6th Air Army was dissolved and seconded to the Polish armed forces to bolster their aviation capabilities. Commanded by a Soviet supporter Gen. Fiedor Połynin it hoped to ensure the Poles remained loyal to their new communist masters.

Through this reorganization, the 1st Polish Composite Air Corps commanded by the Soviet Gen. Philip Agalco, was formed with the 184th Soviet Air Division, now composed of the 1st Polish Bomber Division, 2nd Polish Assault Division, 3rd Polish Fighter Division and the 2nd Liaison Squadron. In addition, the 1st Polish Bomber Division commanded by 2nd Col. V. Bogatov that was part of the 184th Soviet Air Division, incorporated the Polish 3rd, 4th, and 5th Bomber Regiments. The 2nd Polish Assault Division was largely formed from the Soviet 658th, 382nd and 384th Regiments and commanded by Col. Dzemashvili that also incorporated the Polish 1st Training Brigade. The 3rd Polish Fighter Division was formed largely from the Soviet 248th, 246th and 832nd Regiments and commanded by Col. I Chlusovich and incorporated the Polish 10th Training Brigade of the 2nd Air Army which again highlighted shortages in recruitment and delivery of trained personnel to meet the strategic and operational needs. Training kept at a pace so that air reconnaissance ambulance and transport regiments could be added to the overall strength for the ‘push’ to Pomerania and Berlin.

Zamość became the main training centre as extensive damage to Dęblin hampered training schemes and limited the number of Poles who could enter them that now included pre-war reservists in a frantic bid to meet recruitment targets. Their main operations or ‘sorties’ would become focussed on the Pomeranian front throughout February where ground attacks on artillery, vehicles and setting fire to buildings or destroying fortified installations became their prime focus (Krzemiński, 1983; Rapiński, 2018).

At the end of July and beginning of August, the Soviet forces reached the banks of the river Vistula (Wisła) with three bridgeheads at Sandomierz, Kazimierz and Warka districts of Warsaw and just short by 50km of the city (Davies, 2003). The 1st Polish Army’s attempt to set up a bridgehead in the Dęblin sector failed and they were transferred to the Warka sector to reinforce the Soviet army facing stiff resistance from the Germans and their counterattacks. The 1st Warsaw Fighter Regiment and the 611th Assault Regiment provided close support to the 1st Polish Army ground troops with observation and reconnaissance flights over the sector. On 22nd August they moved to the forward base at Zadybie Stare in the Lublin Voivodeship to support the combat hardened and experienced Soviet 233rd Fighter Regiment.

On 23rd August the 1st Warsaw Regiment’s six Yak-1b fighters with two Ilyushin Il-2’s took off at 08.30 to seek German artillery and destroy their positions (Cynk, 1972; 1998). The operation was repeated the following day. On 25th August 1944, the regiment gave covering support for a bridgehead to be developed on an island in the River Vistula at Góra Kalwaria. The following day the squadron made a wide sweep over the district destroying artillery, fuel dumps, transport, and wagons (Cynk, 1972). Railway artillery still posed a threat to the bridgehead and ability to capture the islands that required the squadron to fly reconnaissance sorties to locate and destroy them when located in the Piaseczno area just 16km south of Warsaw on 2nd September 1944.

As the Soviet and Polish forces began to encircle Warsaw, the Polish 1st Kościuszko Infantry Division was operating on the southern flank of the Praga front in a ‘holding operation’. The 2nd Kraków Night Bomber Regiment went into action on 11th to 12th September 1944, reinforcing units from 16th Soviet Air Army. The Soviet and Polish Air Force of the Polish Army had been restricted by operations over Warsaw (Krzemiński, 1983; Kochanski, 2012; Rapiński, 2018) for some ominous reason. By this stage, the Allied Air Bridge from Italy and the FRANTIC operations that had started in June 1944 saw Frantic 7 launched on 1st August 1944 with some limited success. This was part of Stalin’s cynical move to destroy future opposition to Sovietization of Poland (Ciechanowski, 1974; Davies, 2003; Rees, 2009; Kochanski, 2012). (Link: Warsaw Rising - Operation Frantic pages). The Soviets, by grounding its air force enabled the Luftwaffe to pummel Warsaw to the ground.

With air support re-starting in mid-September, the Polish sorties were aimed at harassing the German 19th Armoured Division at Nowe Bródno. With 50 sorties completed; the ground units cleared Praga by the 14th September 1944 after air cover by the Soviets had been re-established. As the pockets of resistance inside Warsaw shrank, the dense smoke from buildings made re-supply drops to the AK more perilous. Although the Soviets made a ‘token’ airdrop, most of the contents were rendered unusable (Kochanski, 2012).

It was not until mid-October 1944 that the Polish Air Division returned to frontline duties with sorties flown by the 2nd Kraków Night Bomber Regiment, bombing key positions along the front for two consecutive nights. On the 15th October 1944, seven assault groups consisting of Il-2s and Yak-1b’s made up of 65 aircraft made several daylight attacks on ground positions inflicting heavy casualties on the Germans with limited Luftwaffe air cover (Krzemiński, 1983). The 2nd Kraków Night Bomber Regiment were in action for four consecutive nights flying 291 sorties (Cynk, 1972). As the autumn approached, Polish Air Division completed 1,989 combat sorties and dropped 232 tons of bombs and successfully destroyed 31 artillery batteries, 33 anti-aircraft defences, 12 searchlights, 244 vehicles and 55 horse-drawn waggons (Cynk, 1972). Polish casualties were relatively light. During the period November to December 1944, the Polish Division was renamed as the Polish 4th Composite Air Division, mainly flew reconnaissance missions (Cynk, 1972; Krzemiński, 1983).

In January 1945, the Eastern Front stretched from the Baltic to the Carpathian Mountains with the renamed 4th Composite Air Division, 12th Ambulance Regiment, 13th Transport Regiment, 17th Liaison Regiment, 4th, and 5th Liaison Squadrons and 103rd Liaison Squadron completing training exercises for the forthcoming winter offensive to support the Polish and Soviet armies in the mid-section of the Vistula (Cynk, 1972; Krzemiński, 1983; Rapiński, 2018). The Soviets launched a wide pincer attack from the north-west and south-west of Warsaw on 14th January 1945 with the Polish army making a frontal attack on the city on 15th January 1945. To support the assault, the 2nd Kraków Night Bomber Regiment were moved to the airfield at Radzymin to the NNE of the city whereupon poor weather with freezing fog grounded support sorties. The weather cleared sufficiently on 15th January 1945 for the bombers to commence attacks on German fortifications with the assault squadrons taking over at dawn to harass the retreating German army from suburb of Modlin (Warsaw’s main airport) and Palmiry, a village on the edge of the Kampinos forest. These sorties were at their most intense between 16th and 21st January 1945 with the bomber squadrons being protected by the 1st Warsaw Fighter Regiment squadrons that destroyed significant military assets of the 47th German Army (Krzemiński, 1983).

In January 1945, the Eastern Front stretched from the Baltic to the Carpathian Mountains with the renamed 4th Composite Air Division, 12th Ambulance Regiment, 13th Transport Regiment, 17th Liaison Regiment, 4th, and 5th Liaison Squadrons and 103rd Liaison Squadron completing training exercises for the forthcoming winter offensive to support the Polish and Soviet armies in the mid-section of the Vistula (Cynk, 1972; Krzemiński, 1983; Rapiński, 2018). The Soviets launched a wide pincer attack from the north-west and south-west of Warsaw on 14th January 1945 with the Polish army making a frontal attack on the city on 15th January 1945. To support the assault, the 2nd Kraków Night Bomber Regiment were moved to the airfield at Radzymin to the NNE of the city whereupon poor weather with freezing fog grounded support sorties. The weather cleared sufficiently on 15th January 1945 for the bombers to commence attacks on German fortifications with the assault squadrons taking over at dawn to harass the retreating German army from suburb of Modlin (Warsaw’s main airport) and Palmiry, a village on the edge of the Kampinos forest. These sorties were at their most intense between 16th and 21st January 1945 with the bomber squadrons being protected by the 1st Warsaw Fighter Regiment squadrons that destroyed significant military assets of the 47th German Army (Krzemiński, 1983).

On 17th January 1945, Polish forces successfully crossed the Vistula and entered the ruined capital. On 16th January 1945 the 4th Composite Air Division were tasked to keep the skies over the city and the bridgeheads clear of enemy aircraft. On 19th January 1945 they also provided air cover for the ‘stylish’ Soviet Victory parade in the city. With the battle of Warsaw completed with a total of 2,166 daytime sorties and 107-night missions completed (Cynk, 1972). Gen. Berling was relieved of his post with Major General Wladysław Korcyzyc temporarily taking over until 1st January 1945.

After the liberation of Warsaw, the 4th Composite Air Division took up reconnaissance duties with the 1st Warsaw Regiment providing fighter cover to disrupt any air raids by the Luftwaffe (Krzemiński, 1983). The protection of rebuilt bridges over the Vistula and the 1st Polish People’s Army occupying Warsaw was prioritized as the Soviet army began pursuit westwards of the retreating Wehrmacht (Krzemiński, 1983).

The 4th Composite Air Division was part of the Pomeranian campaign from mid-February to early April 1945. Their role was air support for the Polish troops attacking the Pomeranian defence Wall from Kołobrzeg to Stepnica. The Polish part of the campaign was initiated in the Toruń-Bydgoszcz area that was quickly liberated and then focussed on crossing the river Oder which was crossed on 30th January 1945. At the end of January, the 4th Composite Air Division was relocated to the liberated airfield at Sanniki and then mid-February to Bydgoszcz during the battle for the Pomeranian Wall. The 2nd Kraków Night Bomber Regiment was to be moved to the rear to Gaj, just south of Kraków, however the move was delayed by bad weather so the whole of the 4th Composite Air Division moved to Bydgoszcz as the Front had advanced over a 100km (Cynk, 1972; Krzemiński, 1983). From here, the sorties were mainly reconnaissance by pairs of Ilyushin Il-2s over Szczecin, a key port on the Baltic coast plus Wałcz, Górnica, Barwice, Czaplinek, Węgorzewo, and Białogard, forming a north-south front in almost the centre of Poland. On one such sortie near Barwice, a transport column and ground troops was spotted with fighters attacking the column in the morning and afternoon supported by Soviet air cover from the 282nd Mixed Aviation Regiment (Krzemiński, 1983).

On 15th-16th February 1945 the Wehrmacht had units encircled at Piły to the west of Bydgoszcz that resulted in intense ground and aerial attacks on transports and railway stations. Some German units attempted a breakout at the rear on 19th February with the Polish Army reserves from Tarnow foiling their escape. During these sorties’ railway engines, carriages and other transports were destroyed. The Poles continued their attacks along the Pomeranian Front at Wierzchowo, Złocieniec and Szczecin (Cynk, 1972; Krzemiński, 1983). Around 20th February transport networks near Szczecin and Złocieniec were attacked to harass and slow down the westward retreat.

For the month of February Krzemiński (1983) listed the 4th Composite Air Division’s tally:

- 1st Warsaw Regiment 391 sorties

- 2nd Kraków Night Bomber Regiment 124 sorties

- Destroyed 300 cars, 21 steam locomotives, 140 horse-drawn carts and 163 railway wagons.

- Lost 5 aircraft (2 Yak-9s and 2 Ilyushin Il-2s and 1 Polikarpov Po-2

On 1st March 1945, 4th Composite Air Division were in action covering the 1st and 3rd Polish Army’s march towards the Baltic coast over Wierzchowo, Żabin and further east Żabinka (Krzemiński, 1983). After completing support for the 1st Polish Army’s assaults on the Pomeranian Wall, attention now focussed on Kołobrzeg, the popular seaside city before the war and what has been a historically contested region (Kochanski, 2012). The Pomeranian Wall blocked Zhukov’s advance on Berlin by several months due to Rokossovsky being ordered to attack the Wehrmacht forces in the north towards the old Prussian city of Elbląg that left a concentrated German force in Pomerania.

A shortage of aviation fuel and poor weather conditions between the 5th to 17th March slowed progress of the 1st People’s Army with limited air cover that also delayed the transfer of 4th Composite Air Division to Mirosławiec in western Pomerania (Krzemiński, 1983). Fresh troops and supplies for the assault on Kołobrzeg came by sea. By this time, the skies above Kołobrzeg had poor Luftwaffe cover that enabled numerous air-strikes on defensive positions held mostly by the SS Heeresgruppe 'Weichsel', whose figurehead commander was Heinrich Himmler.

Krzemiński (1983) listed the 4th Composite Air Division’s tally in the Kołobrzeg front as:

- 127 sorties and 25 bombing missions

- sank a transport ship and 4 barges

- destroyed 9 mortar batteries, 3 field artillery batteries and 27 transports

- set fire to many key military buildings

When Kołobrzeg fell, the 1st Polish Army strengthened shore positions and batteries from potential counterattacks (Link: Polish People’s Army). The duties of the 4th Composite Air Division switched to attacking enemy shipping in the Baltic Sea who were trying to evacuate troops, refugees and concentration camp inmates and clearing occupied islands too. Many of the defenders (40,000) had been evacuated to Gdynia and attempted their escape in Operation HANNIBAL (Buttar, 2010) that left a token group of defenders numbering 2,000 troops inside the city’s defences.

Routine reconnaissance patrols identified V2 rocket launchers on Chrząszczewska Island near Kamień Pomorski in the Kamień Lagoon. Remnants of the Wehrmacht attempted to make their escape through the forests to reach the Szczecin Lagoon (Oder Lagoon/ Pomeranian Lagoon) and take boats or rafts to the German lines. Sorties by the 2nd Kraków Night Bomber Regiment and the 103rd Liaison Regiment played a major role in the liquidation of these troops. 103rd Liaison Regiment was based at Narost, 59km south of Szczecin and uncovered a group of German soldiers in the forest near Chilkiewicz attempting to break through the rear of Front Line and were liquidated.

With Pomerania being cleared of German pockets of resistance, 4th Composite Air Division and the 1st Polish Army now concentrated on the race to Berlin with their Soviet comrades. However, the German pocket centred on Szczecin would not be liberated until 26th April 1945. On 14th April 1945, the 4th Composite Air Division was moved to a forward base at Barnówko between Dębno and Szczecin, not far from the River Oder and reequipped with newer models of the Yak-9s (Cynk, 1972). On 15th and 16th April 1945, sorties targeted German positions around Bad Freienwalde, Neu Ranft, Neurüdnitz and Altreetz on the German border targeting artillery positions in support of the 1st Polish People’s Army. Despite low cloud and fog lying in the Oder valley with vision down to less than 200m, air support continued in these conditions. These sorties continued to pound artillery positions and fortifications around Neurüdnitz whose defences were breached on 20th April 1945 with the 4th Composite Air Division making a significant contribution (Krzemiński, 1983). Between 16th and 19th April, 330 combat missions were flown with 84% flown between 18th and 19th April due to the poor weather conditions (Krzemiński, 1983). The air attacks were important in the destruction of German equipment and defences for Polish ground troops to breach them with close combat formations just above their heads. This enabled both the 1st Polish People’s Army and the Soviet 61st Army to begin pursuit deeper into Germany.

A temporary forward operating airfield was set up at Gozdowice on the banks of the river Oder that enabled improved communications with the advancing ground troops. The air evacuation of the wounded started from this base too. On 20th to 24th April, sorties covered the Polish crossings over the River Oder towards Bernöwe, Oranienburg, the Ruppiner Kanal, Kremmen and Nauen on the northern outskirts of Berlin. Crossing the River Oder was perilous since the bridgehead were underdeveloped for a major assault (Beevor, 2002). The 1st Polish Peoples’ Army and Soviet 61st Army crossed under heavy fire in amphibious vehicles, in US supplied DUKWs driven by young women soldiers and some assault boats that provided little protection. Casualties were high with some units almost annihilated through indecisive decisions by the Soviet senior commanders meant the action was more of a ‘meat grinder’ where volume eventually overcame the stiff German resistance (Beevor, 2002). Once the defences were breached along the west bank, their advance was a spectacular achievement despite the casualty rate. The 4th Composite Air Division used reconnaissance sorties and swift retaliatory actions to neutralize retreating columns of Germans, particularly the mechanised units through anticipating the direction of retreat (Krzemiński, 1983).

Along the front, the level of destruction and the number of fires hung over the area adding to the visual difficulties of the sorties flown who had to recheck the targets prior to strikes. Around the lakes, rivers and canals fog clung to the ground. Calls for air support to attack ground targets were made difficult due to the number of refugees fleeing mixed up with retreating Wehrmacht units, POWs and slave labourers on forced marches (Krzemiński, 1983; Beevor, 2002; Nichol and Rennel, 2002; Hastings, 2005). The Luftwaffe still presented a threat to the1st Polish Peoples’ Army advance and the need for air cover remained a priority during 20th to 24th April 1945. The weather conditions were far from ideal, yet despite this, 305 daytime sorties and 72-night sorties were completed (Krzemiński, 1983). During this period, the 1st Polish Mixed Air Corps (MKL) completed its relocation to Myślibórz (Soldin) behind the Oder where the 2nd Polish Attack Aviation Division (2 DLSz) consisting of the 6th, 7th and 8th Regiment were based. The 3rd Fighter Division (DLM) consisting of the 9th, 10th and 11th Regiment joined them, however, the 1st Bomber Aviation Division remained in the rear due to training of personnel being incomplete. The 1st Polish Mixed Air Corps flew limited sorties on 24th April and covered Polish troops crossing the Hohenzollern Canal in the Hennigsdorf area on the outskirts of Berlin (Krzemiński, 1983)

On 24th April 1945, Polish ground attacks with aerial support were carried out in cooperation with the Soviet 61st Army and successfully repulsed the counterattack by SS Gen. Felix Steiner on the Ruppiner Canal. His hodgepodge Army Group Vistula was now outnumbered (Beevor, 2002) with the Polish Air Force carrying out 412 sorties over this part of Berlin (Krzemiński, 1983). Gen. Felix Steiner’s bridgehead on the Ruppiner Canal came under intense attack by the 2nd Polish Attack Aviation Division (2 DLSz) and the 3rd Fighter Division (DLM) with night-time bombing by the 2nd Kraków Night Bomber Regiment flying over 160 combat sorties (Krzemiński, 1983; Rapiński, 2018). Limited Luftwaffe air support attempted to ease the intensity of attacks on Steiner’s bridgehead to little avail as the 1st Warsaw Regiment patrolled the skies above it and engaged Me-109s (Rapiński, 2018).

On 25th to 26th April 1945, the remnants of the German army attempted to regroup in the Löwenberg Land, Zehdenick, Borksdorf and Nassenheide area some 50km north of Berlin with the 1st Polish Mixed Air Corps (MKL) and 4th Mixed Air Corps (MDL) observing their activities through carrying out 52 reconnaissance sorties that resulted in bombing raids leaving Gen. Steiner unable to counter-attack. Fierce fighting with superior air support meant the German bridgehead in the Germendorf area to the west of Oranienburg, was destroyed with troops falling back over the Moorgraben canal. On 27th April the Polish People’s Army consisting of the 3rd, 4th and 6th Divisions resumed their attack on remnants of the Wehrmacht defences by pushing further west of Oranienburg causing heavy losses. Reconnaissance sorties were carried out to the north of their positions to ensure security from potential counterattack. During this period the 10th Fighter Regiment, led by Capt. Kuznecov, attacked six Ju188 (Rächer) bombers escorted by 12 Fw-190s approaching them across the front line near Velten. That evening, the 1st Warsaw Regiment while on patrol was attacked by 12 Fw-190s near Velten and during the ensuing dogfight shot down 2 Fw-190s with ground fire from AA guns helping to clear the skies (Cynk, 1998)

Between the 27th and 29th April, 1,021 operational and tactical sorties were flown (Krzemiński, 1983) in difficult weather conditions to support the 1st Polish People’s Army that was fighting towards the River Elbe with the Soviet 61st Army on their flanks. 1st Polish Mixed Air Corps (MKL) had moved to new bases close to the front. Grüntal became the operational airfield for 10th Fighter and 6th Assault Regiments with the 11th Fighter and the 7th and 8th Assault Regiments to Steinbeck (Cynk, 1972). Later, the 4th Mixed Air Corps (MDL) was posted to Velten just NE of Berlin for the final assaults on the city. With German ground and air defences severely weakened, reconnaissance and strafing sorties harried the retreating Germans. The 1st Polish People’s Army crossed the River Elbe on 3rd May 1945 and met advance units of the 9th U.S. Army.

Also, on the 3rd May, the Polish pilots met USAAF Mustang (P-51) fighters flying over Havelberg and Wulkau. They used hand signals to greet each other as the Allies fought their way towards Berlin. Next day, the 4th May the commander of the 1st Belorussian Front Marshall Zhukov, suspended all combat operations where only reconnaissance sorties were permitted (Cynk, 1972; Krzemiński, 1983; Rapiński, 2018). However, the order came late as during the day 2 Yak-9s from the 11th Fighter Regiment engaged 4 Fw190s that was probably the last aerial engagement of their war (Cynk, 1998). Although there were small pockets of resistance in Czechoslovakia, Prussia, Hel and Latvia (Kurzeme district) the 1st Polish People’s Army and Air Force had completed their duties.

In the closing days of the conflict, the 1st Polish Mixed Air Corps (MKL) was moved to Schwante and consisted of the 6th, 7th Assault Regiments and the 9th Fighter Regiment while the 10th, 11th fighter Regiments took over the airfield at Eichstadt. In this move the 8th Assault Regiment was relocated to Vehlefanz west of Oranienburg and the 4th Mixed Air Corps (MDL) became established at Möthlow. Overall, the Berlin operation carried out 4,492 operational sorties and managed to destroy 122 artillery pieces, 40 mortars, 17 tanks, 505 transports and over 100 horsedrawn wagons. 72 railway carriages were destroyed along with over 2,860 troops (Cynk, 1972; Rapiński, 2018). Their war was over, but the struggles continued. The harsh winter of 1946 and the inability for the agricultural economies to restart to pre-wartime levels left European’s close to starvation and the prioritizing for feeding the masses and rebuilding infrastructure to provide basic levels of housing, transport, utilities and work (Lowe, 20013). In the Soviet Ukraine it is estimated a million died in the famine (Ganson, 2009) with Europe being spared through the Marshall Plan from April 1948 to 1951.

Postscript:

Although the 1st Polish Mixed Air Corps (MKL) and 4th Mixed Air Corps (MDL) were over-shadowed by their ‘brother in arms’ who flew for the Allies, their achievements should not be overlooked. Many of the pilots were inexperienced, had been pushed through training programmes and provided with aircraft whose age and modernity were questionable. Airframes have a limited ‘shelf life’. According to Cynk (1972) they achieved:

-

13,624 operational flights and 13,976 flying hours over the brutal Belorussian Front

- 5,687 combat sorties

- 57 contacts with the Luftwaffe with 27 confirmed ‘kills’

- 94 casualties

- Lost 36 aeroplanes

Many awards and citations followed and with peacetime the inevitable reorganisation took place. The Soviet pilots and ground crew were returned to Russia. After the Russo-Polish aviation agreement in March 1946 was concluded - the same month Churchill made his ‘Iron Curtain’ speech in Fulton, Missouri, USA, the newly formed Polish Air Force came into being. However, those who returned from abroad did not fare well with the communist authorities. 130 were returned from Pow camps and 75 from the dissolved PAF. Treated with suspicion, some were arrested and executed or imprisoned (Cynk, 1998).

The Cold War officially began with the announcement of the Truman Doctrine in 1947, however, increasing tensions between the Soviets and Allies through a series of events and geo-political friction points left Europe in a perilous state (Hastings, 2005; Lowe, 2013; Sebestyen, 2015). In Poland a civil war in the Kresy region and remnants of the AK fought on to seek independence from Sovietisation until almost 1950. Anti-Soviet feelings were deeply rooted in the Polish psyche through years of partition and the disastrous Battle of Warsaw in 1920 (Kochanski, 2012; Jóźwiak, 2022) and largely remained passively resistant to the Soviets for decades to come. Operation VISTULA (Akcja Wisła) was a civil war (Link: Operation Vistula) that was little known about for decades through the communist controlled media and the brutal suppression by the NKVD of local populations, deportations and imprisonment of political opponents (Link: Trial of the Sixteen). For the Polish forces in Britain, their fate initially ‘hung in the balance’ when the recognition of the Polish Government in exile was rescinded and the Polish Resettlement Corps came into being after a bill was passed in Parliament in February 1946 by Bevan’s government (Link: Resettlement). Soviet control of the armed services prevailed under the new regime with Gen. Aleksander Romeyko taking over the command from Gen. Polynin in April 1947 who would be later replaced by Gen Ivan Turkel (Cynk, 1998). It was not until the coup in 1956 (Poznański Czerwiec and Polski październik) that the Poles regained partial military independence with Gen. Jan Frey-Bielecki taking over and those imprisoned officer released and pardoned (Cynk, 1998; Persak, 2006; Pienkos, 2006).

In the immediate aftermath of the war, the scramble for Nazi technology (Longdon, 2010) almost brought the Soviets and Allies into conflict where the Soviets felt the Allies had sequestered more than their ‘fair share’ in many daring operations even into Soviet held territory. The Soviet stance on reparations from the ‘liberated’ countries and their odd ‘positioning’ under international laws at the Nuremberg Trials between 1945 and 1949 was a forewarning of what was to come. The Warsaw Pact (Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance) concluded on 14th May 1955 was the zenith of Soviet intentions with oppression of eastern and central Europe lasting until 1989 despite numerous revolts in the occupied countries.

Selected References:

Bałuk, S.S. (1995) “Poles on the Frontlines of the World War II 1939-1945”, ARS Print Production, Poland.

Beevor, A. (2002) Berlin: The Downfall 1945”, Penguin-Viking, UK.

Buttar, P. (2010) “Battleground Prussia: The Assault on Germany’s Eastern Front 1944-45”, Osprey Books, UK.

Ciechanowski, J.M. (1974) “The Warsaw Rising of 1944”, Cambridge University Press, UK.

Cynk, J.B. (1972) “History of the Polish Air Force 1918-1968”, Osprey Publishing Ltd, UK.

Cynk, J.B. (1972) “History of the Polish Air Force 1918-1968”, Osprey Publishing Ltd, UK.

Cynk, J.B. (1998) “The Polish Air Force at War: The Official History 1943-1945” Vol. II, Schiffer Military History, USA.

Davies, N. (2003) “Rising ’44: The Battle for Warsaw”, Macmillan, UK.

Drane, L.R. (1976) “Soviet Tactical Air Doctrine”, a report from the Air War College, Air University, Maxwell Air Force Base, USA.

Ganson, N. (2009) “The Famine of 1946-47 in the Context of Russian History” in “The Soviet Famine of 1946-47 in Global and Historical Perspective”, Palgrave Macmillan, USA, Ch 6, pp. 117-135.

Garthoff, R.L. (1958) “How the Soviets Organise their Airpower”, Air & Space Forces Magazine, February edition (Accessed 19.04.2024).

Hastings, M. (2005) Armageddon: The battle for Germany 1944-45”, Pan Books, UK.

Jóźwiak, K. (2022) “Polish Memory of the Second World War and its Afterlife in the Early Cold War Italian Film Culture”, Iluminace, Vol.34, No. 1, pp. 53-71.

Kochanski, H. (2012) “The Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War”, Allen Lane, UK

Krzemiński, C. (1983) “Wojna Powietrzna w Europie 1939-1945”, Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej, Poland.

Longdon, S. (2010) “T-Force: The Forgotten Heroes of 1945”, Constable, UK.

Lowe, K. (2013) “Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II”,

Nichol, J and Rennel, T. (2002) The Last Escape: The untold story of the Allied prisoners of war in Germany 1944-45”, Viking, UK.

Persak, K. (2006) “The Polish-Soviet confrontation in 1956 and the attempted Soviet military intervention in Poland”, Europe-Asia Studies, Vol.58, No. 8, pp. 1285-1310.

Pienkos, D.E. (2006) “A Look Back: Poland and the Historic Events of 1956”, Polish Review, Vol. LI, No.3-4, pp. 371-374.

Rapiński, P. (2018) “1 Pułk Lotnictwa Myśliwskiego ‘Warszawa’ w latach 1943-1945”, Napoleon V, Poland.

Rees, L. (2009) “World War II Behind Closed Doors: Stalin, The Nazis and The West”, BBC Books, UK.

Sebestyen, V. (2015) “1946: The Making of the Modern World”, Pan Books; UK.

Additional References:

Frank, M. (2008) “Useless Mouths: Transfers from Czechoslovakia and Poland, 1946-1947”, in Frank, M “Expelling the Germans: British Opinion and Post 1945 Population Transfer in Context”, Ch.7, OUP, UK.

Howansky-Reilly, D. (2013) “Scattered: The Forced Relocation of Poland’s Ukrainians after World War II”, University of Wisconsin Press, USA.

Lukas, R.C. (1975) “Russia, The Warsaw Uprising and the Cold War”, The Polish Review, Vol.20, No. 4, pp. 13-25.

McGilvary, E. (2019) Red Trojan Horse: The Berling Army and the Soviet Annexation of Poland 1943-45”, Helion & Co, UK.

Motyka, G. (2022) “From the Volhynian Massacre to Operation Vistula: The Polish-Ukrainian Conflict 1943-1947”, FOCUS, Vol. 6, Brill, Germany.

Murawski, E. (NK) “The Struggles for Pomerania. The Last Defensive Battles in the East”, Fedorowicz Publishing, Poland.

Murawski, E. (NK) “The Struggles for Pomerania. The Last Defensive Battles in the East”, Fedorowicz Publishing, Poland.

Naimark, N.M. (2004) “Stalin and Europe in the Postwar Period 1945-53: Issues and Problems”, Journal of Modern European History, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 28-57.

Nowak, C.M. (1986) “The Polish Resistance Movement in Second World War”, Bridgewater Review, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp.4-7.

Piotrowski, T. (1998) “Akcja ‘Wisła’ – Operation ‘Vistula’ 1947: Background and Assessment”, Polish Review, Vol. XLIII, No. 2, pp. 219-238.

Shields, E.J. (2023) “Cooperation, Control, and Compromise: Catholic Church of Poland in a Sea of Stalinist Change, 1945-1956”, The Alexandrian, Vol. XII, No. 1.

Selected Web Sites:

ttps://www.polishairforce.pl/wicherkiewicz.html

oatmeal-tycoon-disguise

http://www.sppw1944.org/index.html?http://www.sppw1944.org/powstanie/przyczolek_eng.html

https://www.memoryofnations.eu/en/peoples-army-poland-soldier

https://warsawinstitute.org/post-war-war-years-1944-1963-poland/

Selected Films and YouTube:

“Czterej pancerni i pies” (1966) Created by Konrad Nałęcki and Andrzej Czekalski for TVP with Janusz Gajos, Franciszek Piecka, Włodzimierz Press, Pola Raksa, Wiesław Gołas, Roman Wilhelmi, Małgorzata Niemirska, Aleksander Bielawski and Tadeusz Fijewski.

Zasieki” (1983) Directed by Andrzej Piotrowski with Edward Apa, Andrzej Bielski, Halina Buyno-Loza and Janusz Bylczynski.

“Siberian Exile” (Syberiada polska) (2013) Directed by Janusz Zaorski with Adam Woronowicz, Sonia Bohosiewicz and Andril Zhurba.

“Pamięć jest naszą ojczyzną” (2020) Directed by Jonathan Durand, Documentary.

The Lost Requiem”, (1983) Directed by Khosrow Sinai, Documentary.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uI5S_VlvlJo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sao9Rof743c Poznań June 1956

|