|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Polandinexile.com is dedicated to the men and women who escaped from Poland to fight in World War II. You will see from their personal accounts and testaments that this was historically a unique event largely ignored by historians. Many of these accounts have been compiled long after the events happened and in many cases diaries were confiscated, lost or deliberately destroyed by either their German or Soviet captors. Where possible dates events and places have been checked with archives and other published references to ensure accuracy. The escapes fall into four basic categories:

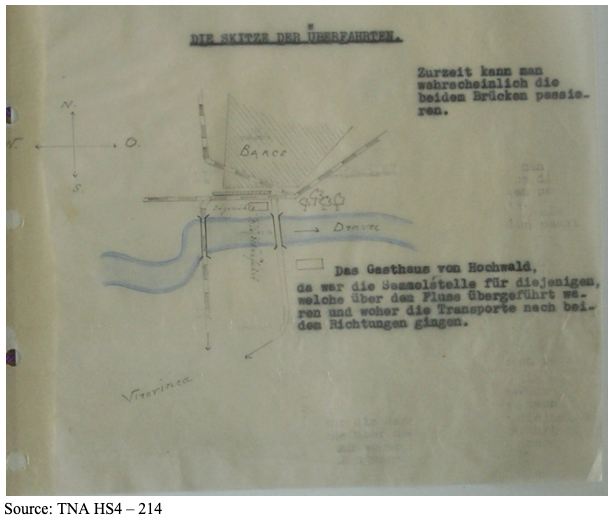

All of these stories have not given graphic detail in the over-coming of the horror, suffering and often appalling or dangerous conditions that had to be overcome in order to survive. Events surrounding the repatriation of those captured by the Soviets are far from satisfactory and remain sinister. The genocide committed by the Soviets remains both unacceptable and inexplicable despite various attempts both during and after the 'Cold War' where pressure to even concede acknowledgement of the horror has failed. These Poles were treated as political prisoners and not servicemen and in the eyes of the Soviets, not covered by the Geneva Convention. The regime within the gulags and other camps in prohibited areas meant certain death. Indeed, the British Government in the year 2000 still has not officially apologised for its part in the 'official' denial of Stalin's role in the cover-up of the murders. The horror of the Katyn Massacre and the deliberate inhumane conditions in the gulags should never be forgotten. In the case of the Katyn massacre only 4,421 are known to have died. Another 4,000 are believed to lie still largely hidden in the forest with another 13,000 or more not accounted for. Recently released archive material indicates Krushchev knew of 10,000 Polish officers being shot in 1940 by the NKVD in two other locations near Russian cities. Anders (1949) estimated that between 1.5m - 1.6m Poles ranging from military personnel to priests and other professional people (including Ukrainians, White Russians, and Jews) were captured and deported from Eastern Poland. Those numbers trickling out of the gulags were substantially less. The Soviets massaged 'records' only showed 475,000 Poles captured. Of the 15,000 prisoners which entered the notorious camps at Kozielsk, Starobielsk and Ostashkov, only a few hundred emerged (Anders, 1949; Lisiewicz, 1949) to re-enlist. Lisiewicz (1949) indicates that of 20,000 Poles sent to the lead mines in Kolyma a few hundred left the camp, but only 20 made it to the recruiting station. Out of 3,000 Poles sent to the lead mines in North Kamchatka in August 1940 only 300 survived and were in the final agonising stages of death from lead poisoning. Requests for further information on missing personnel largely went unanswered. The Eastern Archives, based in Warsaw have evidence from former NKVD files than another 500,000 needs to be added to earlier estimates to attain a truer figure. All of these stories include patriotism; physical and mental hardship mixed with a sense of duty rather than adventure. In many cases an urgent desire to survive in order to fight for the re-establishment of Poland and bring about justice was a driving force. All these stories are unique and need to be told. For younger generations or those unfamiliar with Eastern and Central Europe, follow the stories with the aide of a map to reveal the fantastic geographical dimension to the stories. Evacuation Routes 1939 -1940 The decision to evacuate was based on the notion that after the fall of Poland, its navy, soldiers and airmen would be needed in the defence of France an Britain. Internment was expected in neutral countries like Romania (who had signed an alliance with Poland before the war) Hungary, Latvia and Lithuania. The evacuation was meticulously planned in terms of logistics in civilian clothing, visas and passports despite growing pressure by Germany upon the Romanians and Hungarians to keep the Poles caged up in 'camps' (Lisiewicz, 1949). Almost all those interned in transit camps in Hungary and Rumania escaped between the autumn of 1939 and the summer of 1940 and amounted to 15,978 officers and other ranks to Britain with another 1,378 from other countries. Under pressure, the Hungarian and Romanian governments became anti-Polish while the people remained largely supportive and assisted in escapes. Conditions in the camps were very poor and medical support at best totally inadequate. Shortages of quinine meant many interned in camps in the Danube basin in the region of Tulcea suffered from malaria. More At the outbreak of war, British, Polish and French delegates met at the French Air Ministry, Paris (25.10.39) to discuss how to utilize the Polish armed services personnel now available. General Sikorski had become the new commander in chief and was highly respected by the PAF. The Poles wanted to re-establish their airforce in Britain due to the RAF having superior equipment than the French and they had also been given some training on British made equipment. It was the French who suggested the service personnel should be divided equally for incorporation into their armed services for a speedier reinforcement (Lisiewicz, 1949). Britain agreed to take 300 pilots and 2,000 technical support staff while the residue would be eventually moved to front-line units in France. Group Captain A.P. Davidson who had acted as the Air Attaché in Warsaw had a high regard for the quality and training of the PAF and saw an opportunity to borrow navigators to make up a shortfall in the RAF. The British and French legations in Bucharest were contacted to help General Zajac, the commander of the PAF to help set up a clandestine network for the evacuation of over 90,000 personnel from the Rumanian camps. This was done under the noses of Gestapo agents who now riddled the country, watching all movement and traffic (Zamoyski, 1995). Most escapees were directed to Constanza, Balic or Efori on the Black Sea then via Syria or Malta and then onto France. Another major route directed escapees to Split in Yugoslavia and then by ship to France. Some were directed to Piraeus in Greece (Lisiewicz, 1949; Zamoyski, 1995). Some solo escapees went by foot through Yugoslavia through northern Italy and into France. The programme of evacuation was reasonably orderly despite the frustrations of the internees and anger at the collapse of Poland. The Yugoslavs, Greek and Italians in particular assisted in the evacuation and the crossing of borders. Life in the camps was not easy. Initially someone had to be blamed and so anger was vented on the ineffectiveness of the generals, the Polish Government and factions within the armed services. Added to their problems, the Rumanians and Hungarians were under increasing pressure to detain and keep the internees in camps. Pro-German supporters, particularly in Rumania were openly anti-Polish where personal security was repeatedly threatened. Reneging on agreements and betrayal were common and required corruption of local officials to 'look the other way'. German intelligence and the Gestapo had extensive networks of spies monitoring the internees. Germany protested repeatedly at the lax security in the camps in order to deny the British and French additional trained personnel. After November 1939 camp security was tightened up and officers and other ranks dispersed to Southern Romania. In Rumania as the camp head counts diminished, Rumanians officials regularly falsified returns with 'ghost' numbers to avoid the wrath of their German paymasters Many of the first groups to escape the Balkans were trans-shipped directly to France or made their way by being re-routed to Palestine then via North Africa in a variety of vessels ranging from cargo ships to former cruise and passenger liners. Not all escapees travelled in luxury. Far from it and for many the final leg of the journey to freedom were as uncomfortable as those in the internment camps. When the war in North Africa threatened these routes, longer journeys via South Africa were introduced. For those groups of PAF, who fled to Latvia, they had mainly fought for the 5th Airforce regiment and had been based at Lida. Under pressure from the German army in the west and the Soviets in the east, the remnants were evacuated from Porubanek airfield near Wilno. A twelve-hour dash to the border resulted in disarmament by the Latvians citing international law and being marched to a temporary camp at Zemgale. After three days they were transferred to the fortress at Libau. Latvian Poles assisted in some escapes, but officers were moved to Ulbroki near Riga. Very few made it out via Sweden and Norway to France. The Soviet invasion saw all Polish internees moved to the gulags. The Soviets only changed their minds after 'Operation Barbarossa' when Germany invaded Russia. By then, thousands had been systematically killed and few survived. Lisiewicz (1949) records only 200 PAF came to Britain via Archangel who had been interned in Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. In Hungary over 1,000 members of the PAF were interned after the fall of Poland (Lisiewicz, 1949; Zamoyski, 1995) and were mainly made up of the ground staff of operational units that had flown to Rumania. These units had been cut off by the advancing Soviet army who had deliberately fought hard to take control of the roads and passes to freedom in Hungary and Rumania. By 18th September 1939 the PAF units trapped in the Halicz - Podhajce area had been joined by the 10th Armoured Brigade. The group broke out through the Prut valley on the 20th September and escaped across the Jablonkow Pass in the Carpathian Mountains to Hungary. There were no formal diplomatic ties or agreements with Hungary and so these service personnel expected not only internment, but also harsher treatment than those who had made it successfully to Romania. With uniforms in tatters and worn-out boots, the Poles relinquished their arms and started interment. Through age old ties, the sympathetic Hungarians (Sisa, 1984) began to resettle 100,000 soldiers and the PAF units in camps in the Miskolcs military region in north and north-west Hungary or around the beautiful Lake Balaton. The accommodation ranged from barracks, disused factories or deserted summer resorts. The greatest concentrations of PAF personnel were at Nagy-Kata camp or at Jolsva. Initially the regulations in the camps were lax and the whole experience quite genial compared to their compatriots in Rumania. Self-governance was permitted and visiting local towns required little formality. Like Rumania, German protests attempted to cut the number of 'escapes' or absentee personnel. While camp life was monotonous, behind the scenes preparations were being made under the guise of the Committee for Hungarian - Polish Affairs. Various bodies were set up for the care of both military and civilian refugees for medical, cultural and employment activities. In Budapest, the Polish Red Cross and the Polish Catholic Church were allowed to operate quite openly. Hungarian-Polish activities were well organized and an undercover network was formed. Over 30,000 Poles were clandestinely smuggled over the border to Yugoslavia. As the European war escalated, Hungary became politically trapped. The 'Little Entente' which included Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Rumania collapsed and a treaty of 'eternal frienship' with Yugoslavia signed by Premier Count Pál Teleki at the end of 1940 propelled Hungary to war after a coup in Yugoslavia forced Hitler to invade via Hungary. Count Pál Teleki committed suicide over Hungary's breach of faith. By February 1940 the movement of Polish personnel had become restricted and passports no longer honoured. Visas were being refused for all those aged under forty-five and by then most internment camps held very few military personnel. Evacuations had continued throughout this period despite some pro-Nazi sympathies in the Hungarian military and government. Msgr. Béla Varga became pro-active in assisting the underground movement to enable the escape of hundreds of trapped Frenchmen as well as the Poles. Under his guidance he set up at Balatonboglár a Polish high School and a Lycée to ensure young men and women continued with or completed their education. More. President Hortha appointed Lásló Bárdossy as premier after the death of Count Pál Teleki and Hungary became less tolerant of escaping Poles. The individual escape routes were almost as many as the escapees themselves. Some crossed Germany and into France via the Low Countries while a few made it via the Scandinavian countries. Most crossed the Carpathian Mountains and headed south. At the outbreak of war and the subsequent partitioning of Poland with the Soviets, most passes were strongly guarded. The first winter of the war was harsh. No one has estimated how many either perished in the snow or were hunted down like animals by the Gestapo and NKVD (Lisiewicz, 1949; Pruszynski 1941) and summarily shot. Ownership of skis was punishable by death. The Underground Movement provided guides (Pruszynski 1941; Novak, 1982) for a hazardous journey which lasted about four days for the luckier ones. The mountain ranges were riddled with trails used for smuggling and legends of robbers abound in the folklore of the Goralé. Littered with caves, the area was difficult for the Nazis or NKVD to clear of resistance movements, hence towns like Zakopane in southern Poland became designated 'Sperrgebiet'. Underground movements and Resistance were dealt with harshly by both the Gestapo and the NKVD. More. When Poland fell in September 1939 to German occupation, many Polish POWs escaped and headed south for Hungary where the government was sympathetic to the Poles. Large numbers of "breakouts" caused the Nazis to demand greater control and better security at the camps. Although it was roughly complied with, numerous escapes were known to local officials who acted with little haste. Officers were breaking out and arriving in Budapest where the exiled government provided the means of escape. Germany had originally requested Count Pál Teleki, the Hungarian Premier to allow Hungary to become a springboard for the invasion against Poland which had been turned down. When Poland had collapsed it is estimated over 100,000 soldiers had crossed the border. The Hungarians formed a national movement "Hungarians for the Poles" and was supported by all social strata. The Committee for Hungarian-Polish Refugee Affairs co-ordinated the administration and care of military and civilian refugees which brought together the Hungarian Polish University Alliance, the Hungarian-Polish Scout movement, the Red Cross, and the Catholic Church together with the Hungarian Mickiewicz Society. The Committee for Hungarian-Polish Refugee Affairs co-ordinated the administration and care of military and civilian refugees which brought together the Hungarian Polish University Alliance, the Hungarian-Polish Scout movement, the Red Cross, and the Catholic Church together with the Hungarian Mickiewicz Society. From Budapest, one of the escape routes took the escapees to Osd, Miskoll, Hatuan, Godollo with a final train trip to Kelti. Here the escapees walked to the Yugoslavian border by means of safe houses and guides till crossing the river Drave where the border meanders like the river. Not far from Barcs is an island on the Hungarian side of the border which made crossing into Croatia relatively safe. Then on to Zagreb, Split and a boat to France, usually Marseilles to re-join the Polish Army in France. It is estimated 30,000 Poles were smuggled clandestinely out across the Yugoslav border with passports by an underground Hungarian-Polish network. One of the shortest escape routes was through Croatia. The border with Croatia was an obstacle to individual escapees. However, at Barcs, a small market town situated on the river, the border was a weak point for control. With good access from Budapest, the escape route was secure and hardly watched. The town had a significant Jewish community making up half the population and hostile to the Hungarians (TNA HS4 – 214).

The escaped POWs were assisted by:

Barcs was an ideal location since the local sawmill provided a suitable hiding place and the Hungarian night-watchman was in the former Polish Legions during 1914-1918 war. Elizabeth Pollitzer assisted crossings through her brother obtaining necessary documents for crossing into Croatia. The actual crossing was at Darány, a small hamlet 7 Kms from Barcs where the crossing was ideal in a low populated area and little watched (TNA HS4 – 214) with a sympathetic local mayor. Two other escape lines existed in the area:

It was a daring and highly successful multi-organisational operation providing experienced servicemen and women for Britain’s war effort. Couriers:

Zakopane was a ‘gateway’ through the Tatra mountains and Slovakia to Hungary. Couriers had used centuries old smuggling routes through the mountains often travelling alone or in some cases assisting infiltration of agents or exfiltration of escapees bound for Budapest. In Budapest the AK had a bureau supported by VI Bureau and had collaborative links to SIS (Section D) to assist in the smuggling of W/T sets, spares, currency, and propaganda. Small arms were limited due to weight and distance to be carried.

In the summer of 1945 when the Allies controlled much of Europeand with US army based in Pilsen, couriers and political refugees fleeing the NKVD’s purges and deportations crossed into Czechoslovakia south of Dresden with a Brigade of the NSZ escaping behind the German retreat (Williamson, 2012). Further reading: Williamson, D.G. (2012) “The Polish Underground 1939 – 1947”, Pen & Sword Military, UK.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||