Operation Market Garden

There are a number of excellent texts and websites covering the detail of ‘Market Garden’ from the pre-planning through to the battle (Ryan, 1977; Cholewcznski, 1993) and the rehabilitation of General Sosabowski. For Poles, there remains a strong desire for the rehabilitation and exoneration of the General since numerous post-war texts relied quite heavily upon Montgomery’s ‘adjusted’ account and the role of Brigadier Frederick ‘Boy’ Browning. Only the British could have appointed senior officers whose interests were in ‘realpolitik’ and not airborne operations and to be so heavily involved in not only the strategic planning, but also the operation. And in the aftermath seek a scapegoat who had been extremely experienced; informed; critical and proved correct in the flawed planning and field operations of Market Garden (Buckingham, 2004).

There are a number of excellent texts and websites covering the detail of ‘Market Garden’ from the pre-planning through to the battle (Ryan, 1977; Cholewcznski, 1993) and the rehabilitation of General Sosabowski. For Poles, there remains a strong desire for the rehabilitation and exoneration of the General since numerous post-war texts relied quite heavily upon Montgomery’s ‘adjusted’ account and the role of Brigadier Frederick ‘Boy’ Browning. Only the British could have appointed senior officers whose interests were in ‘realpolitik’ and not airborne operations and to be so heavily involved in not only the strategic planning, but also the operation. And in the aftermath seek a scapegoat who had been extremely experienced; informed; critical and proved correct in the flawed planning and field operations of Market Garden (Buckingham, 2004).

With the collapse of Poland in 1939, Britain and the Allies benefited from airborne (including gliding) and parachuting skills developed by Poles during the interwar years where military and sport parachuting had become quite established. While trains shipped to Scotland some 20,000 Poles after the collapse of France and ‘camped’ in the Glasgow area in July 1940, their initial duties were in the coastal protection. Under the overall command of General Kukiel who was based in London, the 1st Rifle Brigade formed under General Paszkiewicz was put into extensive training and defence building work. During this period plans for developing armoured and parachute divisions were implemented with the 1st Polish Parachute Brigade being formed in October 1941 at Largo House near Leven under the command of General Sosabowski. Amongst the Poles were officers who had served at the parachute-training centre at Bydgoszcz (Sosabowski, 1960; Cholewcznski, 1993; Buckingham, 2004; Peszke, 2005). A special training centre for the Cichociemni had been set up at Inverlochie Castle, which required parachute training skills at that time based at Manchester’s Ringway to be included in their training regime. Lieutenant Julian Gebolys and Lieutenant Jerzy Gorecki were sent to set up the parachute-training centre (Sosabowski, 1960; Cholewcznski, 1993; Loryz, 1993; Buckingham, 2004). Here they set up the training towers and ‘monkey grove’ that were subsequently adopted by British and US airborne training centres, but not always fully acknowledged to the Poles (Buckingham, 2002).

|

|

It must be remembered that the structure, training and operations of the 1st Parachute Regiment operated on different lines to both British and US Airborne units. The 1st Parachute Regiment was being held in ‘reserve’. Sosabowski’s vision of an airborne force required a high level of physical fitness, discipline and commitment where constant training was required and specialization by attached units including communications. A ‘ban’ on seeing wives or girlfriends were not uncommon demands and despite this (and the caricatures/ cartoons drawn by the men) Sosabowski had a devoted following amongst officers and troops.

Both Sosabowski and Sikorski had long come to the same strategic conclusion that when an uprising in Poland started the 1st Parachute Regiment would be critical in the offensive. By September 1943 (Sosabowski, 1960; Cholewcznski, 1993; Loryz, 1993) the Brigade was organized in four battalions comprising of some 2,500 men and were well equiped. The level and quality of training was such that much praise had been heaped upon them. However, they were under the direct control of the Commander in Chief Sikorski who acknowledged the shortages of air transport hindered operations and the strategy was to focus on covert operations by the Cichociemni and other specialist operations like Operation Freston or Wildhorn.

In August 1942 General Sikorski reminded the British commanders that while re-organization of the Polish armed forces were necessary and that action on continental Europe would still be supported through reserves still held in France and Switzerland (2DSP) being used to bolster units in action once the opportunity arose. The 1st Parachute Regiment would be designated to support the (underground) armed movement in Poland and until 1944 was not for re-negotiation.

With the breakout from Normandy in August 1944 the speed of collapse in northern France caught SHAEF strategic planning off-guard. Action by Patton’s 3rd Army required SHAEF to constantly re-evaluate numerous planned set pieces for the capture of France and the invasion of Germany. Early March 1944 SHAEF had requested the Polish High Command to reconsider the role of the Polish Parachute Brigade and release them for combat in Northwest Europe due to shifts in strategic planning and the downfall of Berlin.

On 1st August 1944 at 17.00 (W hour) the struggle for Warsaw started as the result in months of political and ideological pressure upon the Home Army (AK) commander facing the Soviet army and the threat of enforced communist rule while surviving appalling conditions under Nazi rule (Bor-Komorowski, 1951; Ciechanowski, 1974; Davies, 2003). The Warsaw rising was the conclusion of Operation Burza and for 63 days fought against all odds and despite an ill-fated airborne re-supply from Brindisi, the uprising collapsed.

Promises by Field Marshall Sir Alan Brooke for the requisition of transport, gliders and fighter escort (Davies, 2003; Peszke, 2005) to transport the Polish Parachute Brigade to Warsaw when the ‘time was right’ was a hollow and callous in light of the battle for Warsaw.

During September 1944 the invasion of southern Holland had been planned. With the speed at which the Germans had been cleared from France, the Allied airborne forces that were originally intended to leapfrog front lines in a rolling pattern were faced with constant operations being cancelled. The German withdrawal and pace of General Patton’s race across France caused a number of airborne operations to be cancelled causing frustration and dismay at the alternative hastily prepared plans being rushed into place. Operation LINNET scheduled for 3rd September was one such example and was in effect a forerunner of Operation Market Garden where the 1st Allied Airborne Army (comprising of US 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, British 1st Airborne Division and the Polish Parachute Brigade) would drop into Tournai. However, it was cancelled as the town fell the night before the operation was due. SHAEF had to contend with Montgomery’s jealousies (Sosabowski, 1960; Cholewcznski, 1993; Loryz, 1993; Hastings, 2004) and rages while trying to execute strategies, which would result in the final invasion of Germany through southern Germany in the Aachen area.

The death of Sikorski and the collapse of the Warsaw rising left the Government-in-Exile powerless and increasingly isolated (Bor-Komorowski, 1951; Ciechanowski, 1974) as political sympathies within the Allies shifted (Davies, 2003; Hastings, 2004). The raison d’etre for the independence of the Polish Parachute Brigade diminished and Browning at long last had the Poles transferred under his command.

Operation Market Garden

‘Many of the causes of the disaster at Arnhem were readily identified soon after it took place. Market Garden was a rotten plan, poorly executed’. (Hastings, 2004:66)

On the morning of Sunday 17th September 1944, one of the largest airborne assaults droned over Great Britain towards the drop zone in Holland and included fighter escort from the famous Polish 303 Squadron based at Coltishall. Over 2,000 transport aircraft and 478 gliders set off as an airborne armada to breach the western defences and open up the German plains for the final assault on Berlin. Much has been written (and filmed) about the battle. The role of the Poles has been pushed to one side as a ‘side show’ and subject to unwarranted criticism (Sosabowski, 1960; Cholewcznski, 1993; Davies, 2003; Hastings, 2004; Buckingham, 2004). Cholewcznski’s (1993) highly acclaimed account covers the detail of the Polish Airborne assault at Arnhem remains a ‘must read’ for those tracing family history and the events on the battlefield.

The following is about the Polish Parachute Brigades’ role.

|

|

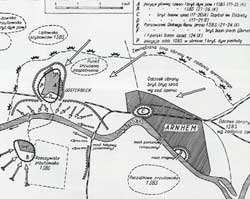

The planned -v- Actual Drop Zone

Both Montgomery and Browning required the Poles to be ready for action by 1st July 1944 despite Sosabowski’s protests indicating August at the earliest as the Brigade was under strength (Sosabowski, 1960; Cholewcznski, 1993; Buckingham, 2004; Peszke 2005). Sosabowski’s rebuff and criticism of the plans for Market Garden became the foundation of a long campaign by the ‘establishment’ under Browning’s direction to discredit the Polish contribution and the leadership of Sosabowski. While it may be true that the ‘Warsaw rising’ placed pressure upon all Polish combatants and not just the airborne brigade for engagement in the battle for Warsaw, the foundation to Sosabowski’s criticism lay in the planning and logistical support. Sosabowski concern stemmed from the sequence of drops and the logistics in supporting a lightly armed airborne battalion (Cholewcznski, 1993; Buckingham, 2004). Indeed, Peszke (2005) argues most of Market Garden was absurd in that the Poles would be dropped without anti-tank weapons on the southern end of the Arnhem Bridge and then re-cross the river to relieve the First Airborne Division when 30th Armoured Corps arrived. Buckingham (2004) also emphasized the absurdity of the RAF not only choosing LZ’s, but also controlling them remotely without any consideration to distance or communications between ground forces and the airdrop crews. Peszke (2005) also recounts the Brigade was also deprived of its small American pack howitzers. These were to be sent by sea and never made it to the battle.

|

|

LZ at Driel 3km from original planned site.

On the second day of operations, September 18th 1944 the first batch of Polish gliders containing anti-tank guns were dispatched to the British held perimeter to the north of Oosterbeek. On 19th September 1944 a further group of 35 gliders were dispatched to Arnhem carrying anti-tank guns and part of the personnel forming the brigade headquarters. Caught by German defence fighters the group landed on the perimeter of the British forces and suffered heavy casualties (Cholewcznski, 1993; Buckingham, 2004; Peszke, 2005) after which the weather closed in and halted all air operations.

The impact of the poor weather delayed the departure and sustained German counter-attacks led to the change in orders. The Polish Parachute Brigade was re-assigned to capture the ferry at Driel (the boat was lost the day before) and boarded their C-47s air transports on 21st September 1944 and took off at 14.00. Shortages in transport required ‘waves’ in drops on the LZ during daylight hours making the ‘drops’ more hazardous and no longer practiced by airborne troops (Cholewcznski, 1993; Buckingham, 2004). Peszke (2005) pointed out that despite transport shortages Browning commandeered 38 gliders to move his headquarters to Holland and thus deprived action, which could have taken the bridge at Arnhem. By late afternoon the Poles were dropped onto a LZ held by a small German infantry unit and not the British as planned. The flight was intercepted by Heeresgruppe B through the Luftwaffe early warning system and alerted a newly arrived flak brigade, which put up a curtain of AA on the run into the LZ (Buckingham, 2004). The Germans mistook the action as a counter-attack to take and secure the southern end of the bridge (they had already captured the full battle plan). However, the flat field bordered by dykes was difficult terrain to secure and an ideal ‘killing field’ for the German defenders. General Sosabowski learnt that the 3rd Battalion had been recalled due to poor weather leaving him in command of less that 1,000 men with no artillery or anti-tank guns and isolated from the British and no ferry (Cholewcznski, 1993; Buckingham, 2004; Peszke, 2005).

|

|

Driel LZ and re-grouping

Poor communication and delays held back the link with the British to the north who were under great pressure (Buckingham, 2004) while the vanguard of 30th Corps helped hold positions and beat back repeated attacks by the Germans.

On 23rd September 1944 the Third Battalion was dropped onto the perimeter of the US 82nd Airborne Division having lost time grounded in Britain. Late on the 23rd September the Poles attempted to link with the surrounded British 1st Airborne. 30th Corps had delivered larger dinghies and the Third Battalion (Polish) were to be ferried across the Lower Rhine in support even though Browning must have recognised the futility of despatching valuable men for little effect (Cholewcznski, 1993; Buckingham, 2004). Although the unit re-enforced the perimeter, they suffered 50% casualty rate (Peszke, 2005).