|

|

The Warsaw Rising

In late 1943 the Russian Army crossed the Dnieper River and created a wedge between the German Armies in the Ukraine and Baltic.

‘The Warsaw Rising of August 1944 was but the last performance of a drama which was also enacted

in 1733, 1767, 1794, 1830 1846, 1848, 1863, 1905, and 1920. On each occasion, if asked what they were fighting for, their [Poles]

reply might well have been the same: for a few ideas…. Which is nothing new’ (Davis, 1981:37). This view almost demeans the careful

planning and courage of the Home Army and related activities associated with one of the largest secret armies in Occupied Europe.

The self-less courage and massive losses inflicted upon the Home Army makes it one of the largest battles fought by ill-equipped combatants whose inspiration

has kept future generations awe inspired. It lasted two months and saw 200,000 die and a city left in ruins while a complacent Russian Army watched from the

banks of the Vistula.

Prelude to the Warsaw Rising

Strategically, the German High Command had been expecting an attempt to breakout of Soviet held territory and Hitler ordered a stand to defend

Warsaw at all costs (Iranek-Osmecki, 1954; Bor-Komorowski, 1951; Ciechanowski, 1975). The possibility of a Soviet attack on the city had been foreseen

by the Home Army and the Government-in-Exile. Sikorski’s failure to settle the frontier problem had left a political stalemate steeped in deep recrimination in

Soviet-Polish relations (Ciechanowski, 1975). The inability to cooperate also stemmed from Stalin’s refusal to release details of the whereabouts of Polish

officers until the discovery of the Katyn Massacre in April 1943. Anders constant complaints about release of Polish personnel from the Gulags and

non-recognition of citizenship during the formation of the Second Polish Corps in the Middle East added to the impasse (Bor-Komorowski, 1951;

Ciechanowski, 1975; Davis, 1981). The constant debate about frontiers and the adoption of the ‘Curzon Line’ dragged on despite efforts by Churchill and

Roosevelt. In the autumn 1943 Bor-Komorowski was desperate for the Home Army to have diplomatic contact with the Soviets and was being pressurized

by Eden to accept the Curzon Line. Mikolajczyk’s saw this as an opportunity to co-operate and establish the recognition of the Home Army to secure weapons

and administrate the undisputed territories (Ciechanowski, 1975). Most political leaders saw the dispute as a major block to post war settlement and the

Government in Exile remained intransient to any agreement or rapprochement with the Soviets who remained suspicious of Stalin. Sosnkowski remained

concerned over Bor-Komorowski independence and the strategic value Operation Burza and its impact upon disputed territory. In addition he was more

concerned over the scope and free-range Churchill and Roosevelt had given the Soviets in Central and Eastern Europe (Ciechanowski, 1975).

Operation Burza (Storm also sometimes called Tempest)

The Home Army issued orders to implement Operation Burza to harass the retreating Germans in almost all

districts despite not being granted combatant rights.

The plans for the Warsaw Rising were amended according to a constant updating by field intelligence. The

Soviets supported the AL and there were conflicts in

numerous operational districts, which forced Bor-Komorowski to concentrate operations in an area bordered by the Rivers Bug and Stochod and centred on the

town of Kowel (Iranek-Osmecki, 1954; Bor-Komorowski, 1951; Ciechanowski, 1975).

The Home Army issued orders to implement Operation Burza to harass the retreating Germans in almost all

districts despite not being granted combatant rights.

The plans for the Warsaw Rising were amended according to a constant updating by field intelligence. The

Soviets supported the AL and there were conflicts in

numerous operational districts, which forced Bor-Komorowski to concentrate operations in an area bordered by the Rivers Bug and Stochod and centred on the

town of Kowel (Iranek-Osmecki, 1954; Bor-Komorowski, 1951; Ciechanowski, 1975).

|

District |

Home Army Divisions |

|

Vilna and Nowogrodek |

1st, 19th and 20th |

|

Brest - Litovsk |

30th |

|

Volhynia |

27th |

|

Lvov |

5th |

|

Lublin |

3rd, 9th and 13th |

|

Bialystok |

18th and 29th |

|

Radom and Kielce |

2nd and 7th |

|

Warsaw |

8th, 10th and 28th |

|

Krakow |

6th, 22nd and 24th |

(Source: Iranek-Osmecki, 1954:173)

The Soviets supported by the AL were not to be trusted.

Local contact with the Soviet army often resulted in liquidation of leading field operatives,

particularly the Cichociemni or whole units disarmed and imprisoned in former concentration camps (Majdanek) or deported to the gulags in Russia once

action was completed. In operational districts like Volhynia the contact was in two fronts - harassing the Germans and avoiding the Soviets. In some operational

districts the Home Army were so successful that they controlled the area apart from some major towns. Arms dumps were captured and prisoners released

and in some cases members of the AK released from serving.

Members of the Home Army despite spearheading many battles in the run up to the liberation of Warsaw were barred from entering captured towns and cities as

this reduced the impact of Soviet propaganda. Those who did manage to escape and return to their secret camps were eventually surrounded and liquidated

(Iranek-Osmecki, 1954).

The Warsaw Rising

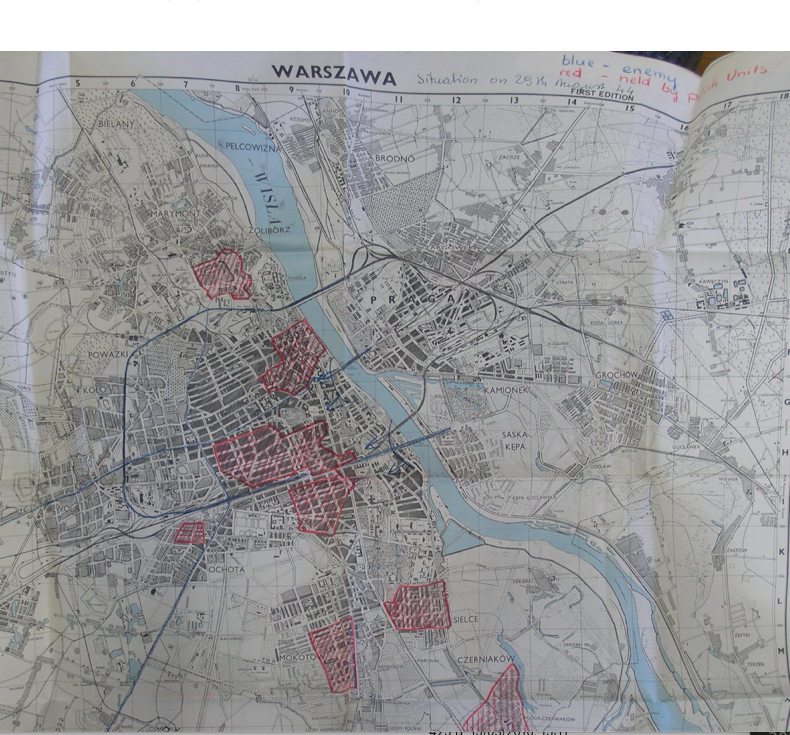

When the Soviet army reached the eastern outskirts of Warsaw and entered the district of Praga, the final stages of operation Burza were implemented.

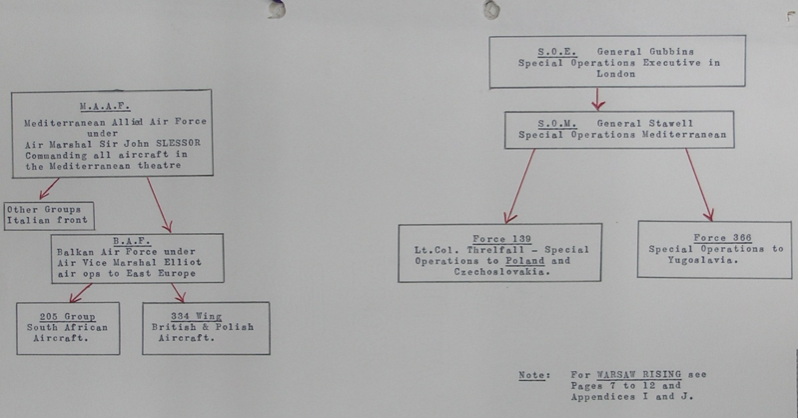

On the 26th July the Government in Exile had formally asked the British Government for support (Foot, 1990). Churchill and Gubbins watched the unfolding

tragedy in an almost powerless state. The AK had remained throughout the war as an independent army with little support from the SOE. The Government in

Exile remained fiercely independent of British and American interference and the Polish section of the SOE (known as MP) was run by Colonel Perkins also

had need of special liaison group (EU/P) headed by Major Hazell to avoid duplication or strategic clashes (Marks, 2000). The complex relationship within the Polish community caused frustration for all. The geographic distance made operations almost impossible

to support even at the fall of Italy.

When the Soviet army reached the eastern outskirts of Warsaw and entered the district of Praga, the final stages of operation Burza were implemented.

On the 26th July the Government in Exile had formally asked the British Government for support (Foot, 1990). Churchill and Gubbins watched the unfolding

tragedy in an almost powerless state. The AK had remained throughout the war as an independent army with little support from the SOE. The Government in

Exile remained fiercely independent of British and American interference and the Polish section of the SOE (known as MP) was run by Colonel Perkins also

had need of special liaison group (EU/P) headed by Major Hazell to avoid duplication or strategic clashes (Marks, 2000). The complex relationship within the Polish community caused frustration for all. The geographic distance made operations almost impossible

to support even at the fall of Italy.

Many as a commander saw Count Bor-Komorowski out of his depth both politically and strategically (Foot, 1990). On the 1st August 1944 the order for the

Rising was made and Moscow Radio called for support. Soviet tanks were less than 12 miles away and Berling’s army was on the opposite bank of the Vistula

and gave limited support due to the orders of Soviet High Command. Berling was dismissed for sending over patrols to

assist the heroic AK actions against the

Germans. Appeals for arms were made and the SOE and the RAF did what little they could, but the flight was 900 miles from base and on the edge of

operational limits with dropping zones close to city limits and only a few miles from the Soviets. Requests for the Polish Airforce to fly to Poland together with an

airborne drop of the Polish Brigade were also out of the question (Garlinski, 1969). Specialist paratroopers who had been trained for operations in Northern

France (Operation Bardsea and Monica) were also withheld and kept at their base just outside Peterborough (Foot, 1990; Marks, 2000) such was the risk.

Many as a commander saw Count Bor-Komorowski out of his depth both politically and strategically (Foot, 1990). On the 1st August 1944 the order for the

Rising was made and Moscow Radio called for support. Soviet tanks were less than 12 miles away and Berling’s army was on the opposite bank of the Vistula

and gave limited support due to the orders of Soviet High Command. Berling was dismissed for sending over patrols to

assist the heroic AK actions against the

Germans. Appeals for arms were made and the SOE and the RAF did what little they could, but the flight was 900 miles from base and on the edge of

operational limits with dropping zones close to city limits and only a few miles from the Soviets. Requests for the Polish Airforce to fly to Poland together with an

airborne drop of the Polish Brigade were also out of the question (Garlinski, 1969). Specialist paratroopers who had been trained for operations in Northern

France (Operation Bardsea and Monica) were also withheld and kept at their base just outside Peterborough (Foot, 1990; Marks, 2000) such was the risk.

When 15 out of 16 Polish manned Halifax’s loaded with arms and munitions were shot down, Sir John Slessor, Commander of the Mediterranean forbade any

further flights (Foot, 1990). Weather, low drop altitude, constantly changing city territory and Anti Aircraft fire made it an extremely hazardous mission and could

not be compared to supplying the French Resistance prior to D-Day where the sites were in remote rural areas. Some surviving crew members actually walked

and hitched from crash sites back to Brindisi in Italy through Soviet and German lines. The Soviets under pressure from Roosevelt allowed just one flight, a group

of 110 B-17 US bombers to refuel at Poltava on Soviet held territory for a drop on 18th September 1944 (Garlinski, 1969).

When 15 out of 16 Polish manned Halifax’s loaded with arms and munitions were shot down, Sir John Slessor, Commander of the Mediterranean forbade any

further flights (Foot, 1990). Weather, low drop altitude, constantly changing city territory and Anti Aircraft fire made it an extremely hazardous mission and could

not be compared to supplying the French Resistance prior to D-Day where the sites were in remote rural areas. Some surviving crew members actually walked

and hitched from crash sites back to Brindisi in Italy through Soviet and German lines. The Soviets under pressure from Roosevelt allowed just one flight, a group

of 110 B-17 US bombers to refuel at Poltava on Soviet held territory for a drop on 18th September 1944 (Garlinski, 1969).

The ground battle was desperate with selfless valour being displayed in street-to-street fighting (Davies, 1981). It is estimated there were

between 12 - 20,000 AK soldiers (up to another 75,000 people involved in auxiliary roles) committed to the fight against a well-armed and trained German

Army of 20,000 battle-hardened troops made up of SS and Wehrmacht units.

Although some units of the AL were involved in the action, the lack of tanks,

armoured cars and heavy calibre weapons meant their role made little impact upon the outcome. Bor-Komorowski’s hope that the AK could take and hold

Warsaw for the return of the Government in Exile was politically ill conceived. The Soviets had no intention of recognising the AK and its leaders. The Warsaw

rising and the annihilation of the resistance by the Germans sped up the ‘removal’ of a political obstacle for post war settlement. After 63 days of savage fighting

the city was rubble and the reprisals brutal. The RONA brigade led by Kaminski specialized in anti-partisan action was made up of the scum and deserters of the

Soviet army supported Oskar Dirlanger’s Brigade and other units in vile retribution.

The ground battle was desperate with selfless valour being displayed in street-to-street fighting (Davies, 1981). It is estimated there were

between 12 - 20,000 AK soldiers (up to another 75,000 people involved in auxiliary roles) committed to the fight against a well-armed and trained German

Army of 20,000 battle-hardened troops made up of SS and Wehrmacht units.

Although some units of the AL were involved in the action, the lack of tanks,

armoured cars and heavy calibre weapons meant their role made little impact upon the outcome. Bor-Komorowski’s hope that the AK could take and hold

Warsaw for the return of the Government in Exile was politically ill conceived. The Soviets had no intention of recognising the AK and its leaders. The Warsaw

rising and the annihilation of the resistance by the Germans sped up the ‘removal’ of a political obstacle for post war settlement. After 63 days of savage fighting

the city was rubble and the reprisals brutal. The RONA brigade led by Kaminski specialized in anti-partisan action was made up of the scum and deserters of the

Soviet army supported Oskar Dirlanger’s Brigade and other units in vile retribution.

Mass shootings in reprisal together with the burning of hospitals with staff and

patients was typical of the ‘clean-up’ operations. Women and children were tied too tanks as protection against ambushes. Approximately 550,000 inhabitants

were sent to a concentration camp at Pruszkow and another 150,000 used as slave labour while over 245,000 died. 93% of the city was uninhabitable and

featureless of landmarks. Wehrmacht sappers systematically demolished the city.

Mass shootings in reprisal together with the burning of hospitals with staff and

patients was typical of the ‘clean-up’ operations. Women and children were tied too tanks as protection against ambushes. Approximately 550,000 inhabitants

were sent to a concentration camp at Pruszkow and another 150,000 used as slave labour while over 245,000 died. 93% of the city was uninhabitable and

featureless of landmarks. Wehrmacht sappers systematically demolished the city.

The Warsaw Rising gave Stalin the opportunity to remove a well-organized

army and paved the way for the imposition of a post-war puppet government. Those who did survive would be dealt with at the infamous trials and tribunals

where long-term imprisonment or execution was guaranteed.

The Warsaw Rising gave Stalin the opportunity to remove a well-organized

army and paved the way for the imposition of a post-war puppet government. Those who did survive would be dealt with at the infamous trials and tribunals

where long-term imprisonment or execution was guaranteed.

Air-bridge Statistics

1st August - 2nd October 1944

|

Flights |

306 |

91 Polish

50 British

55 South African

110 American |

|

Drops |

192 |

149 over Warsaw

43 over Kampinos and Kabacki woods |

|

Dropped |

2154 containers

557 Packages |

1711 over Warsaw

443 over Kampinos and Kabacki woods

Total 239 Tons |

|

Success Rate |

742 Containers

381 Packages |

463 over Warsaw

279 over Kampinos and Kabacki woods

182 over Warsaw

199 over Kampinos and Kabacki woods

Total 88 Tons (36.8%) |

(Source: Garlinski, 1969)

Aftermath of the Warsaw Rising 1944

Numerous texts have dealt with the 'Rising 44' in both Polish and English, looking at the events as they unfurled or the strategic decisions behind the event. With 93% of the city destroyed and approximately 550,000 inhabitants sent to a concentration camp at Pruszkow, what parts the city left standing was destroyed systematically by Wehrmacht sappers.

While the Soviet Army (1stByelorussian Front) was halted on the banks of the Vistula and Berlingís Polish Peoples Army sat almost passively as the city capitulated, Soviet control remained firm. To openly disobey would have resulted in another Katyn massacre or internment in Siberia.

Further south the Slovak Rising was being crushed by the Wehrmacht. German forces supported by Einsatzgruppe H, led by Colonel Josef Witiska and the Dirlewanger Brigade, led by the 'Butcher of Warsaw' Colonel Oskar Dirlewanger together with the 18th SS Horst Wessel Panzer Grenadier Division systematically crushed the revolt in southern Slovakia.Golian had pleaded for the Second Independent Czech Paratroop brigade to be flown into Tri Duby by the Soviets. By 15th October 1944 the rising was crushed and the delayed support by the Soviets bore strong similarities to the events in Warsaw.

While Berlingís 1st Polish Peoples Army engaged German frontline units around Praga, action was in a 'holding' position in preparation for the 'January Offensive'. Across the river the fate of the city and its survivors took on a deepening proportion of suffering and in-humanitarian conditions. Despite the capitulation agreement and recognition of the fighters 'legitimacy' to bear arms and be treated under the Geneva Convention (Davies, 2003), the 'surrender march' on 3rd October masked the true horror of capitulation for both the AK and the surviving civilians.

The British Government dithered over Poland in 1944 with the Foreign Office under Anthony Eden regularly blocking fact-finding operations on the state of Poland. British Liaison Officers (B.L.O's) under Operation Freston had been planned to carry out such a mission that by the time they were active in the field too much had changed for the operation to be effective and were compromised by the Soviets. The Freston team were arrested and eventually transported to Moscow. While negotiations for their release took place, the British Government considered using them to verify the current state of Poland and the support for the provisional government under the Lublin Committee.

It is not true that the British Government were uncertain of the post-Rising 44 events. The Government in Exile found Churchill pre-occupied with other concerns. While the rift between the Foreign Office and SOE may have affected communications, a report had been smuggled out of Poland via Sweden and has remained almost forgotten.

Colonel Alexander Björklund who had once been the Finnish attaché in Warsaw had married a Pole and became the representative for the Swedish firm Ericsson. His report is a harrowing read. As the Soviet forces approached Warsaw, the SS units began to clear civilians from several districts like Srodmiescia to Pruszkow. Districts adjoining Filtrowa were moved to fields in Mokotowski which included Björklund and his family. Left without food or water for several days, the SS units continued to beat and humiliate civilians including pregnant women or some simply beaten to death. Björklund became separated from his family and they were eventually reunited in Sweden after the Swedish Legation based in Berlin got permission to leave. Björklund's daughter, Maria Kietlicz-Rayska also reported the events in Warsaw. Her account details their expectations of the Rising. With the Soviet army close at hand and air drops by the RAF, there was hope for freedom. Hungarian troops passing through Warsaw were selling their medical kits and supplies as the AK prepared for action.

Conditions in Warsaw began to change when peasants driven out of eastern territories ahead of the advancing Soviet army. After the 15th August 1944 a greater influx of retreating Germans began and afterwards starving Hungarian troops whom the Gestapo was harassing. A Hungarian officer advised Maria Kietlicz-Rayska that all maps had been removed from them in March 1944 and were advised they were being taken to the Hungarian border while in reality they were taken to Modlin.

Her account of the clearing of civilians during the Rising paints a brutal picture. She describes the forced march through the burning houses in Grojecka street into Zieleniec, the old vegetable market. As the streets were cleared, grenades were thrown into the houses and cellars. In Zieleniec 15,000 people were denied food and water for 5 days with the SS soldiers taunting them. Food for cattle was passed into the starving crowd and owners of pet dogs watched in horror as the soldiers butchered the dogs before passing them back as provisions. Women died in labour, some civilians chocked to death from the smoke from burning houses and women as young as 12 years old were raped.Mrs Niepokojczyck cared for the ill and dying without any regard for her own safety. On 4th August they were ordered to kneel down to be executed, then ordered to line up in threes to be marched off for possible execution. On 5th August a German Luftwaffe unit segregated the Poles from the Volkedeutsch and other nationalities. In groups of about 14 people were marched to the barracks at Okecia and then onto Grodziska (?) or PruszkÛw. In the barracks there were many units of the German army and SS drawn from Eastern Russia and the Baltic states and were unsettled by the advancing Russians. Warsaw was now a forbidden city to visit with any attempt punishable by death. Many Poles escaped on the march and in the confusion were able to survive by declaring themselves to be Hungarian. Maria Kietlicz-Rayska and her family escaped to Lodz and then onto Poznan in search of the Swedish Legation who had re-located to Berlin.

150,000 Poles who were forced out of Warsaw became slave labourers while over 245,000 more died. Please visit the Warsaw Uprising Museum while visiting the city of Warsaw.

Operation FINCHAM

Introduction:

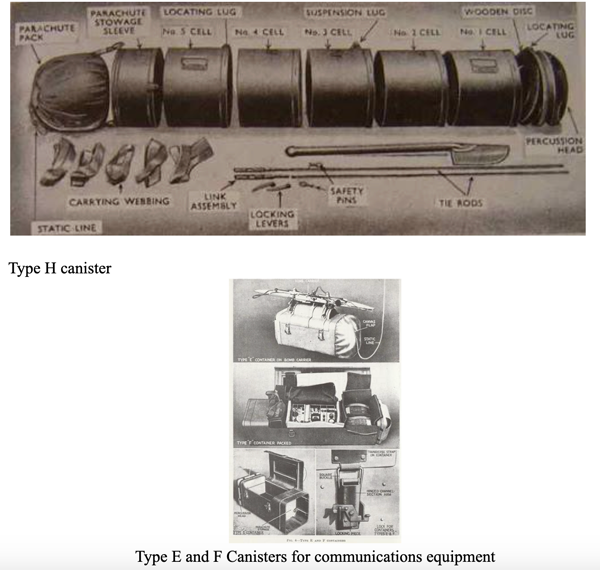

As concerns grew over the likely outcome of the Warsaw Uprising and the low success rate of the air-bridges where only 36.8% (Garlinski, 1969) of the cannisters and packages got through, the thought that Operation FRANTIC 7 would provide the relief to the AK was misplaced (Hyperlink: Operation Frantic). This propelled forward another rescue mission that indicates SOE and some members of the British government had not given up on the courageous Poles. It is in the backdrop that FINCHAM was born.

The Planned Mission:

On 27th September 1944 an internal memo to Maj. Stroud at the Packing Station 61 indicated 126 Liberators (this was changed to Lancasters fitted with the No. XIV bombsight). It was suggested the Polish 300 Squadron (Ziemi Mazowieckiej) based at Faldingsworth could be included in the operation (TNA/ HS4-171). 12 containers would need to be dropped from each aircraft (TNA/ HS4-171), however Lancasters could only accommodate 10. 1512 containers would be required and although Station 61 had stocks of Type III CLE numbering 1130 with Area 8 reporting 180 and Tempsford a further 202 units. The packing instructions covered weapons, medical supplies, uniforms and tinned milk. Amongst the order was a request for 1800 delayed opening devices that were essential to the operation. To fulfil the equipment and medical supplies, a frantic audit of supplies was held in Station 61 (Gaynes Hall), Area H (Holmwood House, Holme), Tempsford, M.E. 10 (Milton Ernest Hall, Bedfordshire), Rattlesden, Bury St. Edmunds and Great Ashfield took place.

Due to the short period, if the medical containers were not ready then C1/ 7.92 containers would replace them. The inventory indicated they would need 126 SPP container type, 504 type C.12 and 378 C/ 7.92. With a constantly changing situation on the streets of Warsaw, the AK requested changes to the mix in arms and equipment to include more food and boots. The barometric delayed action devices were in Italy at Brindisi (Quilter mechanisms) and were dispatched to Britain.

The ground held by the AK was shrinking and these ‘pockets’ were measured to assist the drop. The measurements were:

- Triangle in city centre 2,100 x 2,500m

- Stare Miasto 1,100 x 900m

- Mokotów had two areas: 900 x 1,400m and 900 x 1,200m

- Czerniaków 1,400 x 2,200m

- Żoliborz 900 x 900m

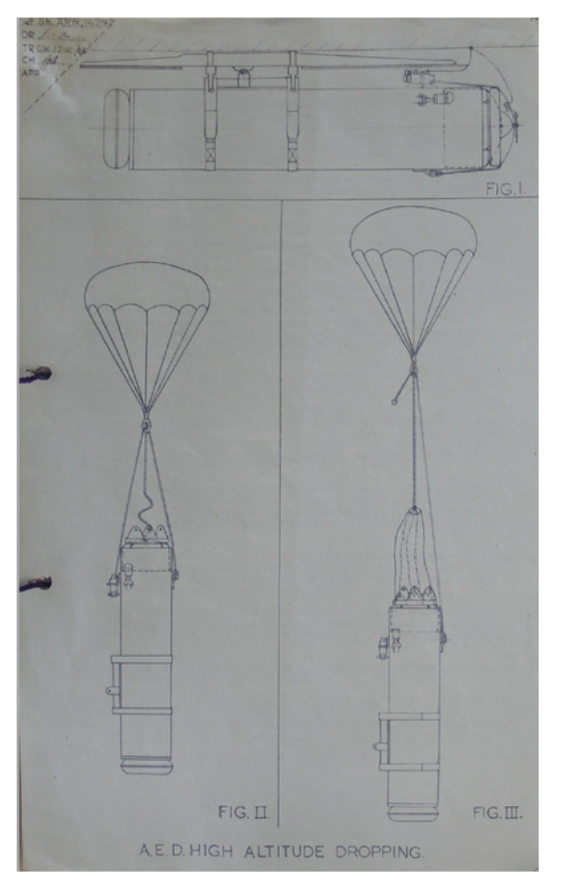

For the containers to be able to land in such tight urban areas, a new parachute opening device had recently been tested for operations from 10-12,000ft and 5,000ft with success (TNA/ HS4-171) with trials including opening at 1,000ft. The existing Quilter mechanism was deemed inaccurate for this mission. The new mechanism would be attached to a Type III CLE.

The specifications for the mechanism (by RAE) indicated it would take 3 weeks for enough devices to be made at M.E. Bickford, but this was reduced to 3 days as a priority. The High Altitude Dropping – Special Operations was not only confronted with technical challenges, but also internal wrangling over ‘permissions’ for manufacturing and the actual drop.

Operation FINCHAM was aborted with short notice sometime after the 27th September 1944. The effort in planning, Quartermasters and packing stations, never mind the pressure to improve and manufacture HALO devices, seems such a waste of resources and effort.

Top of Page

|