|

The Independent Carpathian Rifle Brigade

1 Samodzielna Brygada Strzelcow Karpackich

Formed in April 1940 in Syria under the command of Colonel Stanisław Kopański, the

Independent Carpathian Rifle Brigade (Samodzielna Brygada Strzelców Karpackich) was

formed from those who had escaped or fled from Romania. The first recruits were posted

to a depot at Homs (once called Mesa) on the former Silk Route and now part of Syria.

The desert conditions and the poor barracks in the French Army camp were poor resulting

in the deterioration of the men’s health. The French Levante Army ‘hosted’ the Poles and

relations were reasonably amicable, but with the collapse of France posed a new threat to

the Poles who had been in transit for many months. The French Levante Army was commanded

by General Mittelhauser who received orders on 20th June 1940 for all armed men to ‘lay

down their arms’ using force if necessary (Anders, 1949, Koskodan, 2009). However, local

difficulties had to be overcome through the careful negotiations by Colonel Kopański.

Orders had been received from the Supreme Commander Sikorski to place themselves under

the British in Palestine. The whole Brigade (4,038) moved by train to Palestine in full

arms and kit.

On arrival in Palestine, the Independent Carpathian Rifle Brigade (SBSK) was based at El Latrun halfway between Tel-Aviv

and Jerusalem where conditions were better and morale improved. The Polish army had been moulded around the French army’s

structure and also methods in control and command. Integration and re-equipping with British equipment together with

defensive training took place in August 1940 so that the Brigade could be moved into defensive positions around Jerusalem

where they stayed until 30th September when they were transferred to Alexandria in Egypt leaving only an Officers Legation

behind (consisting of two companies) to receive newly arrived recruits who had escaped via the Balkans.

|

|

Parade at El Latrun 29th June 1941 receiving Brigade and Officers Colours

|

The Italian campaign in North Africa maintained pressure upon British High Command to fill gaps in the overall British Army’s front line, which required the SBSK to be mechanized and leave their precious cavalry behind and at this point the brigade consisted of 348 officers and 5,326 men. The brigade’s artillery had been ‘earmarked’ for use in the defence of Greece, but increasing pressure by the Italians in Libya, particularly around Tobruk altered their destination.

Anders original HQ in Iraq at Quizil Ribat which he described as ‘several primitive little huts, and

were surrounded by a sea of tents pitched on sand of the desert’. Life in Iraq for the survivors of the Russian

deportation and exodus still remained harsh with the evacuees suffering from the after effects of malnutrition

and abuse through to coping with desert conditions, malaria and disease epidemics. Spirits remained high through

training even though there was a shortage of arms and complete uniforms. Social events and the comprehensive use of

theatre productions or special educational programmes were set up to relieve boredom and help with rehabilitation.

In mid April 1941 the SBSK together with the 1st South African Brigade were sent to Mersa Matruh, which was part of a chain of

fortified camps along the Egyptian coast. Here acclimatization and training for desert warfare began through rebuilding

the heavily damaged defences and getting used to the sand storms (chamsin). In mid June 1941 the brigade was

relocated to Sidi Baugh another fortified camp on the North African coast where the brigade completed its mechanization

through being issued with light troop carriers.

|

|

Sidi Bagush

|

|

|

Tcarrier training

|

In June 1941 the ICRB were ordered to relieve the decimated Australian troops on the front lines defending Tobruk. Their arrival coincided with General Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Corps capturing the El-Agheila fort and a string of strategic locations from Mersa Brega, the Halfaya Pass and Bardia.

Tobruk 1941

The siege of Tobruk had started on 31st March 1941 and was a long protracted defensive operation fought under siege

conditions. The ICRB were assigned to a 29Km sector sandwiched between the 25th and 26th Australian Brigades. Under

Operation TREACLE, SUPERCHARGE and CULTIVATE, a huge operation was employed to bring in fresh troops and

supplies to support the besieged city during a moonless period. The Poles were shipped aboard HMD Latona and three

other destroyers to Tobruk in cramped conditions (Lyman, 2009). Under operation TREACLE the ICRB would land and replace

the 18the Australian Brigade, 18th King Edward’s Own Cavalry, Indian Army and the 152nd Heavy A-A Battery (Lyman, 2009).

The Poles were concentrated on a 10Km sector opposite Medauar hill, which had previously been manned by the Australian 18th

Brigade and known as ‘The Gap’. At first, the Australian response to the Poles was one of bemusement since the

Australians were keen to be rid of the desert heat, sandstorms and the constant bombardment from artillery and bombing. On the

other hand the Poles were ready to unleash their vengeance and appeared to relish the idea of going to battle

(Koskodan, 2009). The defences at Tobruk were a series of semi-circular defensive rings around the port. In places old and

abandoned Italian defences mainly made up of small concrete bunkers had been adapted by the Australians for shelter. The

defences were primarily made from rock hewn from the desert and painstakingly built and maintained during the siege.

Opposite the Poles was the Italian 17th (Pavia) Infantry Division. The Italians were in well-maintained dugout positions

overlooking the Polish positions. The Polish forces were made up of 2nd and 3rd Battalions and the Carpathian Ulan’s while

the 1st Battalion was in the rear positions. Due to the desert conditions and topology of the landscape, and not forgetting

the heat, the Poles operated at night with devastating psychological and physical effect capturing men and equipment during

these daring raids. At night the no-mans land became killing fields. ‘The Gap’ had changed hands with many

losses many times while the Australians had been in the line. The Poles earned a fearsome reputation and held onto their

positions from September through to November 1941 with the area around Ras el Madauer being the bloodiest of battles.

|

|

Ulan

|

The Supreme Commander General Sikorski visited the troops on a morale boosting exercise on the 13-14th November 1941 while on

his way to Moscow for talks with Stalin. The visit was to prime the troops in preparation for Operation CRUSADER,

which began on 18th November. Operation Crusader was launched from Egypt across Libya to block Rommel’s next

offensive and caught ‘The Desert Fox’ off guard.

On 20th November 1941 General Sir Ronald Scobie, commander of Tobruk’s joint forces ordered the breakout and the ICRB

assisted in breaching the lines and meeting up with the British (Desert Rats) 8th Army at El Duda. The Poles had been

ordered to start diversionary action along the western perimeter and Medauar Hill to draw German and Italian attention away

from the main objective. Supported by artillery cover from the 1st Polish Artillery Regiment (1 Pułk Artylerii) the

infantry broke through and used bayonets to clear last traces of resistance and held these positions until the 8th Army had

linked up with the break-out forces. While the Tobruk lines held, the battle in the desert was a mixture of success or

confusion caused by poorly trained troops, inadequate equipment, and weak leadership (Lyman, 2009). On 25th November Rommel

launched an attack on Sidi Omar on the Egyptian border in an attempt to destabilize British operations. The Tobruk force

attacked and held onto the southern ridge forming the perimeter between El Duda and Belhamed. It was an intensive battle,

but had to hold onto these key positions and awaiting the link up with the 8th Army who was fighting a desperate battle in the

desert.

On 3rd December Rommel assembled a force to counter-attack the strategic position at El Duda with the initial assault

repulsed. Later in the day a second attempt broke through the lines and was only repulsed when accurate artillery fire

from the Poles inflicted substantial casualties and kept the escarpment secure. This was the turning point for the battle for

Tobruk.

On 12th December 1941 the Brigade started offensive actions along the Derna (Darnah) Road sector and advanced on El Gazala. On

15th December the Poles led the attack on El Gazala, which represented a major obstacle to operation Crusader

(Koskodan, 2009). After a 3-day battle the Poles smashed through the German and Italian lines at Acroma with 1,693 prisoners

taken.

By the end of December 1941 the brigade’s artillery were positioned near Bardia (Bardiyah) and the main forces were in

operations to clear units of the Italian Brescia Division in the Dernah-Anunzio sector. On January 25th 1942 the Poles linked

up with the Free French Brigade and assumed the defence of the stronghold at Mechili.

In March 1942 the brigade was returned to Palestine.

Polish Army in the Middle East

Deliverance From Hell And The Formation Of The II Polish Corps

Operation Barbarossa was launched on 22nd June 1941 with Germany breaking its non-aggression pact with Russia and there

is evidence to suggest Russia was about to launch an attack on Germany within days under the code name Icebreaker

(Suvorov, 1990). It was in reality the second invasion of Poland through the Soviet occupied zone in the eastern provinces

acting as the bridgehead into Russia.

On 14th August 1941 a formal pact was signed between Russia and Poland allowing a new Polish army to be formed from those

captured and deported to the Gulags, mainly in Siberia. The doors were literally flung open and the prisoners were left to

make their way south by any means in the harshest conditions imaginable (Anders, 1949; Peszke, 2005; Koskodan, 2009). The

process of organizing an army in the Middle East was an astonishing tale of endurance and dedication. During the initializing

process General Józef Zając was appointed commander by Sikorski and arranged the transportation of 33,069 troops plus

10,879 civilians (including 3,100 children) from camps based at Krasnovodsk and Ashkhabad on ships across the Caspian Sea to

Pahlawi in Iran between 26th March and 10th April 1943 followed by a second shipment between the 8th and the 30th August 1942.

|

|

Caspian

|

In Iran a series of transit camps had been set up at Qazvin, Tehran, Hamadan and Arak to deal with the influx. Field

hospitals dealt with the sick that suffered from malnutrition, typhus, dysentery, and malaria. Troops were ‘re-screened’ for

all records had been lost and issued new uniforms. The second evacuation covered 40,131 soldiers who now formed 3rd, 5th and

6th Infantry Divisions, 7th Reserve Infantry Division, the Armoured Brigade, 12th Uhlan Regiment, 2nd Sapper Brigade, and

auxiliary units. Accompanying the troops were the 1,765 volunteers of the Women’s Auxiliary Service, 2,738 young men and women

who had survived the labour camps and formed the Labour Auxiliary Service plus a further 25,501 displaced civilians. All

were transported from transit camps like Qazvin in lorries through Iran. The evacuation was a remarkable feat since the

Poles set up schools, printed papers and allowed young people to complete university. Along the route the young Poles adopted

a young bear cub Wojtek who came to feature and prominence in the Italian campaign.

|

|

Wojtek - young bear cub

|

|

|

Transportation lorries

|

In Iraq the units were dispersed in location due to their size and also needs for re-training. The 3rd Infantry Division was

based in Mosul and Rawanduz on the Iran-Kurdistan border until 4th August 1943 where it was moved to Kirkuk. From 22nd March

1942 until 4th December 1943 the 5th and 6th Infantry Division was based at As-Sa’diyah with the 7th Infantry Division being

held in reserve at Khanagin. The 12th Uhlan Regiment was also formed in Iraq and the ‘tankers’ were trained on Valentine and

Sherman tanks and in mid July 1942 were also deployed to Khanquin. The Polish auxiliary services were also set up and were

vital in freeing up manpower for active duty.

|

|

Womens Auxiliary

|

As units became battle ready they were then transferred to Palestine to complete their training. The II Polish Army Corps

headquarters was based in Gaza and consisted of huts and tents in the sandy desert. In September 1942 the whole Corps went on

manoeuvres in different locations where Mount Sinai was stormed and Nazareth ‘captured’ as the units honed their field and

battle craft. General Maitland Wilson commented on how well the II Polish Army Corps performed and were deemed battle-ready.

General Sosnkwski attended the march past of the II Corps at El Khassa-Isdud on 14th November 1944. The Corps was then

transferred to Egypt and located in Ismalia and Al-Quassasin as a staging post for deployment in Italy.

The Polish Prime Minister, Mr Mikolajczyk was at ‘violent differences’ with General Sosnkowski (Anders, 1949) of control and

command powers of the armed services, which resulted in II Polish Army Corps being re-organized. As a result several thousand

men were to be transferred to the Polish Air-force in Britain. Anders opposed the decision and many young men particularly

those who had pre-war training in gliders were prioritized for training.

The Polish fleet consisting of the destroyers Krakus and Slazak escorted M.S Batory and S.S Pulaski

were sent to Egyptian ports for the embarkation of the troops and all equipment. It took from the beginning of December 1943

until middle of April 1944 to move the whole corps to Italy.

Order of Battle Polish II Corps

Drugi Korpus Wojska Polskiego

Commanding Officer: General W. Anders

Deputy Commander: Major General Z. Bohusz-Szysko

|

II Polish Corps Troops

|

Artillery

|

Major General R. Odierzynski

|

1st Polish Survey Regiment

7th Polish Anti-Tank Regiment

663rd Polish Air OP Squadron

567th Searchlight Battery

8th Polish Heavy AA Artillery

|

|

|

Army Group Polish Artillery

|

Colonel K. Zabkowski

|

10th Polish Medium Regiment

11th Polish Medium Regiment

12th Polish Medium Regiment

13th Polish Medium Regiment

78th Medium Regiment

9th Polish Heavy Regiment

|

|

|

HQ II Polish Corps Polish Engineers

|

Colonel J. Sochocki

|

4th Carpathian Rifle Battalion

5th Carpathian Rifle Battalion

6th Carpathian Rifle Battalion

|

|

|

3rd Carpathian Rifle Brigade

|

Lt. Colonel G. Lowczowski

|

7th Carpathian Rifle Battalion

8th Carpathian Rifle Battalion

9th Carpathian Rifle Battalion

|

|

5th Kresowa Infantry Division

|

Artillery

|

Major General Sulik

|

Colonel J. Orski Commanding:

5th Wilenska Field Regiment

5th Wilenska Anti-Tank Regiment

5th Wilenska Light A-A Regiment

7th Polish Horse Artillery Regiment

23rd Field Regiment

|

|

|

Engineers

|

|

4th Kresowa Filed Company

5th Kresowa Field Company

6th Kresowa Field Company

5th Kresowa Field Park

|

|

|

|

|

Company

|

|

|

|

|

5th Kresowa Machine Gun Battalion

|

|

|

|

|

25th Wielkopolski Reconnaissance Regiment

|

|

|

2nd Polish Armoured Brigade

|

Major General D. Rakowski

|

1st Polish Armoured Cavalry Regiment

4th Polish Armoured Regiment

6th Lwowski Armoured Regiment

9th Polish Field Troop (Engineers)

|

|

|

4th Wolynska Infantry Brigade

|

Lt. Colonel W. Stoczkowski

|

10th Wolynski Rifle Battalion

11th Wolynski Rifle Battalion

12th Wolynski Rifle Battalion

|

|

|

5th Wilenska Infantry Brigade

|

Colonel Kurek

|

13th Wilenski Rifle Battalion

14th Wilenski Rifle Battalion

15th Wilenski Rifle Battalion

|

|

|

6th Lwowska Infantry Brigade

|

Colonel Sawicki

|

16th Lwowski Rifle Battalion

17th Lwowski Rifle Battalion

18th Lwowski Rifle Battalion

|

|

3rd Carpathian Infantry Division

|

1st, 2nd and 3rd Rifle Brigade

|

Major General B. Duch

|

1st Carpathian Rifle Battalion

2nd Carpathian Rifle Battalion

3rd Carpathian Rifle Battalion

4th Carpathian Rifle Battalion

5th Carpathian Rifle Battalion

6th Carpathian Rifle Battalion

7th Carpathian Rifle Battalion

8th Carpathian Rifle Battalion

7th Lubelski Uhlan Regiment (Divisional Reconnaissance)

1st Carpathian Light Artillery Regiment

2nd Carpathian Light Artillery Regiment

3rd Carpathian Light Artillery Regiment

3rd Carpathian Anti-tank Regiment

3rd Light Anti-aircraft Regiment

3rd Heavy Machine Gun Battalion

3rd Carpathian Sapper (Engineer) Battalion

1st Carpathian Field Engineer Company

2nd Carpathian Field Engineer Company

3rd Carpathian Field Engineer Company

3rd Carpathian Field Park Company

3rd Carpathian Signals Battalion

|

The Italian Campaign

The first unit to leave was the 3rd Infantry Division who had left Egypt on 21st December 1943. The majority of units

disembarked at Taranto although some were sent to Bari and Brindisi to ease pressure on the ports. In total it took six

transports to move the II Polish Army Corps to Italy. The whole of the 2nd Armoured Brigade landed in Naples. All the units

were quartered in five camps strung along the Taranto-Monopoli road like a ‘string of pearls’ in the San Teresa area which was

well located and liked by the troops since the olive groves gave some protection from the air activity and the roads were in

good order (Madeja, 1984). However, the harsh winter conditions also meant the troops were at risk from infection and epidemics

and also the cold. As the Corps finally came to full strength they were moved towards Barlotta in order to relieve the 78th

British Division.

Defensive Operations on the Sangro Line

31st January until 15th April 1944

In January 1944 the Italian front was at stalemate. The landings at Anzio had lacked the effectiveness and ‘punch’ intended to

rapidly enter Rome due to poor leadership, which enabled the Germans to build and re-enforce a series of defensive lines across

Italy. The US 2nd Corps had failed to take the strategic site at Monte Cassino and an attack in February by the New Zealand 2nd

Corps made little headway. The Polish II Corps had spent the first months in Italy in a passive defensive role on the Sangro

River from north of Pso del Monte to Castel Vincenzo. The 45Km sector was vital in that the Polish corps was wedged between

the British 5th and 8th Armies in order to protect their flanks and hold the front along the river Sangro, which in turn allowed

lateral inter-army communications to take place. II Polish Corps remained attached to the 5th and 8th Armies in terms of major

action and was basically ‘holding the line’ with patrols and localized actions taking place. On 13th March 1944 the 5th Kresowa

Infantry Division joined the front as preparation for the spring offensive got underway. They were ordered to relieve the

2nd Morocco Division, which was part of the French Expeditionary Corps and took over the area around Castel San Vincenzo. It

was around this time the politics of the ‘Curzon Line’ spilled over into the soldiers’ lives in Italy (Anders, 1949). The

Eighth Army News published a pro-Soviet article criticising Poland’s stance on the Curzon Line and General Anders complained to

the US Supreme Commander in Italy, General Leese, that these Polish troops were survivors of Soviet labour and prison camps.

The spring weather and poor conditions of the terrain hampered operations, so most operational activity was unit rotation into

reserve to keep up the strength of the forces and bringing forward munitions and food to various ‘jump-off’ points which

included man-handling 17 pound anti-tank guns weighing 2.5 tons. The rugged terrain meant mule trains carried the corps needs

on their backs and were invaluable in their part they played in the Italian Campaign.

|

|

3crd

|

|

|

Spring Patrol

|

|

|

Mule train

|

|

|

Jump off point

|

Monte Cassino

The battle for Monte Cassino has been described as one of the most toughest and controversial battles of World War II. Numerous

books have been written on the subject and some are listed at the end of the page.

|

|

Monte Cassino

|

|

|

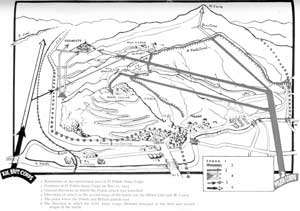

Map of Monte Cassino

|

Four attempts were made to dislodge battle hardened German troops of the 4th and 5th Infantry Divisions and a machine-gun

battalion from 1st Parachute Division from Monte Cassino. The region was ideal defensive terrain (Anders, 1949) for the German

Army to utilize and build the Gustav Line and Hitler Line. The II (US) Corps led the first assault in January where the corps

would advance towards Rome and their attack was stalled by the defences of the Cassino hills (Anders, 1949, Madeja, 1984, Van

der Bijl, 2008). The monastery had commanding views of the Liri valley and formed part of the Gustav defences, which were

deemed impregnable and therefore held the allied advance in check (Koskodan, 2009).

The second attempt was again led by the II (US) Corps supported by the French Expeditionary Corps in February 1944 and again

was unsuccessful. The New Zealand Corps (consisting of the 2nd New Zealand and 5th Indian Brigades) made the third attempt in

March and some important gains were made, but the defensive lines remained intact despite heavy artillery barrages and bombing

of the monastery. During this period Poles who had been forced into the German army and now POW’s were being screened and sent

to 7th Reserve Division in Palestine for training to make up for unit losses (Anders, 1949). Some 35,500 additional troops were

recruited in this way. Sir Harold Alexander, C in C of the Allied Armies in Italy requested a change in strategy which led

General Mark Clark of the US Fifth Army and General Gruenther to revise plans for the Cassino area which were completed on 25th

April 1944. Pressure was needed in the Italian campaign to remain diversionary and prevent the Germans releasing front-line

troops to support the defence of the French Coast from the planned allied landings and also break the lines between the

Tyrrhenian Sea and the Monte Caira massive which would enable linking up with US forces in the Anzio sector. II Polish Corps

were informed of their role to capture Monte Cassino on 24th March and Anders staff interviewed commanders of previous assaults

of their experiences, reconnoitred the terrain by land and air in readiness for action (Madeja, 1984).

The II (US) Corps under operation DIADEM led the assault up route 7 towards Rome with the French Expeditionary Corps attacking

through the Arunci Mountains. The British 8th Corps would cross the River Garigliano on the western flank and advance up the

Liri valley towards Rome. II Polish Corps were assigned the crossing of the River Rapido and assault Monte Cassino and isolate

the German forces from the Gustav Line. The combined weight of the US and British forces was punch through the Gustav and

Hitler Lines.

From 27th April until 11th May the II Polish Corps moved units into forward positions for the ‘jump-off’. The rocky terrain

meant the troops dug small ‘sangers’ to protect them from shrapnel and flying splintered rock. Water was rationed and no

cooking of hot meals could take place, forcing the troops to survive on dry rations. Over 7,000 special camouflage suits for

snipers and specialist commandos from 6th Polish Troop had been delivered along with flamethrowers and special entrenching

tools (Madeja, 1984). On 6th May action was seen across the front with the French making progress and the 5th Kresowa Division

attempted to take Hill 593 with 20% casualties in the process after clearing bunker to bunker in order to secure the heights.

Anders ordered withdraw due to the unacceptable casualties.

In the late afternoon of 11th May Polish and German artillery ceased their duel. The Polish units were in the ‘jump-off’

points from the previous night and the silence was uncanny. The Germans had used this time to start relief operations not

knowing the size of the force now facing them. To avoid suspicion, after a few hours Polish gunners reopened artillery fire.

At 2300 hours the whole of the 8th Army artillery went into action and at 2340 the Polish Corps artillery switched onto their

objective, the infantry positions on Monte Cassino and kept up the barrage until 0100 on 12th May when the Polish infantry

crossed the start lines (Anders, 1949).

The 1st Carpathian Rifle Brigade was assigned to capture Massa Albaneta, Hill 593 and Hill 569 with some armoured support. The

Podhale Reconnaissance Regiment was deployed along the Colle d’Onofrio in defensive positions to protect and provide fire

support from the flank. It took about forty minutes of hard fighting for the first objectives to be reached. Colle San

Angelo, Hill 593 and 575 had been assigned to the 5th Kresowa Division and they had met stiff resistance from German units

dug into the gorge. After several infantry attacks supported by tanks, the northern slopes of the gorge were taken, but the

floor of the gorge was heavily mined and despite attempts by sappers to clear a route fire from Massa Albaneta forced a

retreat. The 2nd Battalion of the Carpathian Rifle Brigade came under heavy fire on the southern slopes of Hill 569. The

Germans had a network of strong well-concealed bunkers and were able to fire upon the 2nd Battalions positions from the

monastery and from Colle d’Onofrio. The 2nd Battalion fought off six counter-attacks by 1130 and the Podhale Reconnaissance

Regiment on the flank also came under pressure from a counter attack. Most units were under constant well placed mortar and

small arms fire. The rear positions were also exposed to artillery fire from Belmonte Atina. After heavy fighting and high

casualties, Hill 569 fell to a German counter attack at 1130.

The 5th Kresowa Division’s attack on Colle San Angelo went according to plan with the 6th Lwow Brigade supporting their right

flank on Monte Castellone and the 5th Wilno Brigade attacking Phantom Ridge with the 17th and 18th Battalions in reserve

(Madeja, 1984; Van der Bijl, 2008). The 6th Lwow Brigade carried out diversionary tactics to relieve pressure upon other

sectors. Throughout the battle, constant artillery barrages had kept German units underground. The 5th Wilno attack on

Phantom Ridge proved to be more difficult due the lethal cross-fire from well concealed bunkers and sangers built into the

terrain of rock and scrub slowing down the action. The German counter attack at 0630 on units on Hill 517 was beaten off,

but the action was made more difficult by bunkers towards their rear had not been fully cleared until the 18th Battalion joined

the mopping up action.

|

|

Phantom Ridge

|

On 12th May the Corps Commander Anders withheld further commitment of troops to Phantom Ridge until 13 Corps Artillery had

secured its bridgehead and the Corps was in better shape which resulted in Phantom Ridge being abandoned and units re-grouped.

General Leese agreed with Anders to stand down further action until artillery and mortar fire could deal more effectively with

the concealed bunkers containing German artillery and mortars, particularly those situated on the lee of the slopes. The

British 8th Army had also encountered strong resistance and had only achieved their second objective on 13th May when the road

from Matronola to Case Petrarcone had been captured. The British had seen the high casualty rates on the 13th Wilenski

Battalion and agreed to postpone any further major action until the reserve British 78th Infantry Division had crossed the

Pytchley Line and started to advance on Highway no. 6 (Madja, 1984).

Polish artillery continued to bombard key sections of the front while the Polish forces re-grouped. Air support targeted the

concealed German artillery on Massa Albaneta. On 14th May tanks from the 4th Armoured Regiment engaged positions in the gorge

so that sappers to clear a pathway through the minefield. During the previous night the German 1st Paratroops Regiment were

withdrawn from the line and sent to reinforce positions against the British 4th Division. Field intelligence was gathered from

night patrols probing enemy positions, which had accurately located mortar positions in pre-preparation for the second assault.

On 17th May 07.00 the 13th Corps and the II Polish Corps re-entered the battle. 3rd Carpathian Division captured Massa

Albaneta and Hill 569 while the 5th Kresowa Infantry Division captured Phantom Ridge before switching their assault onto San

Angelo and Hill 575. Casualties were high and despite supporting fire from Polish artillery, the Germans attempted to counter

attack. Tanks in support of the 5th Kresowa Infantry Division descended the southern slopes of the Phantom Ridge to support

the infantry. The attack on the Colle Santa Angelo by the 16th and 17th Battalions was initially a success, but with the 17th

Battalion low on ammunition and caught in heavy artillery and mortar fire from Pizzo Corno and Villa Santa Lucia, they could

not hold off severe counter attacks and even resorted to throwing rocks to hold their positions (Van der Bijl, 2008). This

meant the Germans were able to recapture the southerly peak of Colle Santa Angelo. The 16th and 18th Lwowski Battalions with

a commando unit were brought into action and finally the southerly peak of Colle San Angelo fell at 18.05 with the troops

digging in for the night. Such were the casualties in the 5th Kresowa Infantry Division that B Echelon personnel and troops

from 5th AA Artillery and Anti-Tank Regiments were drafted into the battle. By the end of the day the 3rd Carpathian Division

had held onto the northern, southern and eastern slopes of Hill 593 and needed the additional support of the 5th Carpathian

Battalion, which had been held in reserve. The German defences had been cleared through tough hand-to-hand fighting and

repulsing vigorous counter attacks. Over two hundred sorties had been flown to bomb hidden mortar positions and now there were

signs of the defences beginning to crumble. The Poles were also aware that an escape may be made so throughout the night

large patrols were kept up in most sectors and the German 1st Paratroops Division did disengage and withdrew to the Gustav and

Hitler Lines.

On 18th May 5th Kresowa Infantry Division continued its bitter assault and the Germans remained stubborn to the end. This

resulted in taking out individual isolated positions and a surprise counter-attack in the vineyard area repulsed. 3rd

Carpathian Rifle Division renewed their assault and by 1030 the Monastery had fallen with the Polish flag flying above the

ruins. By the end of the afternoon most Polish units were in holding defensive positions with Hill 575 and some bunkers on

the Colle Santa Angelo still not cleared or captured. The 8th Army had advanced further up the Liri valley and had punched

through the Gustav Line. Germans holding onto the Pizzo Corno and Monte Caira were eventually capitulated after a two-day

operation by the Carpathian Lancers and 15th Poznan Lancers and by 25th May action had ceased.

The battle for Monte Cassino was crucial to the opening up of Italy for the Allies to advance on Rome. The high level of

casualties was of great concern both then and now: 1,150 killed and 2,629 wounded in just six days of fighting. However,

General Mark Clark has been criticised for placing too greater attention on the liberation of Rome for the sakes of history

rather than using the landings in Anzio to crush the Gustav and Hitler Lines, thereby blocking the escape routes for the

German Army. His strategy was hurriedly put together and strategically indecisive in objectives. The Italian campaign was

tough on both the armies and civilians caught up in the war zones where significant destruction to the infrastructure has

often been forgotten.

The Adriatic Coast Campaign

In the aftermath of Monte Cassino II Polish Corps were feted by London’s press and helped quash leftwing press supporting

Stalin’s stance even if it was short-lived (Anders, 1949). The Corps was exhausted and units depleted, but were re-tasked

to capture the heavily fortified town of Piedmont, which had been incorporated into the Hitler Line (Anders, 1949; Madeja,

1984; Van der Bijl, 2008). Piedmont had been turned into a fortress with an extensive minefield to be negotiated by attacking

ground forces. Piedmont was outside the range of the main II Polish Corps artillery and the overstretched Corps assembled

spare units to form the ‘Bob Group’ (Madeja, 1984). The group composed of 6th Armoured Regiment, 18th Lwow Rifle Battalion,

and the 5th Carpathian Rifle Battalion and supported by the 9th Artillery Regiment using self-propelled guns (Anders, 1949).

The group were also charged with protecting the right flank of the 8th Army whose main action was in the Liri Valley along

Highway 6. Due to congestion on Highway 6, the Bob Group assembled in open ground. The 21st Indian Brigade launched their

attack with the 6th Polish Armoured Regiment on 19th May at 1615 taking the Germans by surprise. Although the initial attack

breached the lines a second attack at 2000 penetrated the centre of the town, but heavily defended buildings left the forces

vulnerable.

A fresh attack was launched on 21st May, but heavy artillery and mortar fire hampered the attack with tanks and self-propelled

guns picking out specific bunkers and providing covering fire for the infantry. By late afternoon the infantry were inside the

town clearing buildings by buildings, but as dusk fell withdrew to the outskirts of the town walls for protection.

|

|

Bob Group

|

The 8th Army requested that action to clear Piedmont should be more about a containment operation in light of the depleted and

exhausted Polish forces. A further attack was launched on 22nd May and again the defences were penetrated, but the narrow

streets hampered mechanized activity to support infantry. The terrain favoured the defenders and again units retreated to the

previous night’s position except for one group that was surrounded and spent the whole night fighting its way back to Polish

lines. With the breach of the Hitler Line by the Canadians on 23rd May, Piedmont became a ‘thorn’ in the flesh. Artillery

pounded the town into rubble and during the night of the 24-25th May the Poles beat off a counter attack. The 13th, 15th and

5 Wilno Brigade was brought in to relieve the Bob group. On 25th May the attack was launched at 0600 with 13th Battalion

capturing Hill 553 and the 15th Battalion supported by tanks captured Piedmont at 0700. From 26th May little engagement with

the Germans was reported and the II Polish Corps was withdrawn to Campobasso leaving the 5th Kresowa Infantry Division detached

units to defend Monte Caira, Pizzo Corno and Monte Castellone (Koskodan, 2009). Sapper units began to repair damaged bridges

and clear landmines.

|

|

Sappers

|

|

|

Piedmont

|

Adriatic Coast and the Battle for Ancona

As the allies pushed into Italy, supply lines became more stretched so the strategy switched to capturing Ancona to ease

pressure on Bari and Brindisi making the action on Adriatic coast higher priority and urgent. On 17th June II Polish Corps was

now in pursuit with the 3rd Carpathian Division rapidly moving forward to prevent the bridges from being blown as many rivers

were in flood conditions. At the Chienti River, the Germans had dug in and repulsed attacks. The Germans appeared to be

preparing a major counter attack when suddenly withdrew. Italian partisan units (Maiella Band) assisted the Poles in their

action at Chienti and Esino rivers (Madeja, 1984).

The ‘dash’ for Ancona accelerated with the crossing of the river Chienti on 21st June with teams of sappers clearing

extensively mined roads and forward units clearing rearguard action by the Germans on the river Potenza. The Germans had

no time to re-enforce defences on the river Musone, which in effect was the last obstacle in the way to Ancona. On 2nd July

the heights on the northern bank of the river Musone were captured. The village of Loreto was a desperate battle to gain

strategic ground and after eight days of action, which included bombing of positions at night by remnants of the Luftwaffe,

re-supply of troops and munitions was possible. Once the airfields at Forli, Rimini, Ravenna and Ferrara were put out of

action, II Polish Corps enjoyed greater safety now the Allies had air-superiority. The Gdansk Reconnaissance Squadron

equipped with cameras provided accurate intel from sweeps over the Adriatic coast.

Anders improvised battle plans for the taking of Ancona by keeping the right flank in a holding position and engaging

diversionary action while on the western flank an assault would enable the defences to be punched through. The 5th Wilno

Infantry Brigade who was reinforced by the 3rd Carpathian Rifle Battalion and the 4th Armoured Regiment with a blanket of

artillery fire to soften up the defences captured the ridge at Monte della Crescia-Offanga. The mechanised operation on the

right flank consisted of the 2nd Armoured Brigade with the 15th Poznan Lncers working in concert with the British 7th Queen’s

Hussars with the infantry support of the 6th Lwow Rifle Brigade with Polish Commandos.

The German lines were broken on the Polvergi axis on 17th June after a hard day of engagement under a heavy artillery barrage

laid down by the Germans. The 5th Wilno Infantry Brigade with the 3rd Carpathian Rifle Battalion captured Monte della Crescia.

The 2nd Armoured Brigade crossed over the river almost un-noticed and captured Monte Torto, the ridge at Gorce di Santa Vicenzo

and Monte Bogo. By 18th July the 6th Lwow Infantry Brigade with the 2nd Armoured Brigade had reached the shores of the Adriatic

with the Germans hastily withdrawing units from the Ancona region. The 18th Carpathian Lancers entered Ancona and captured

over 2,756 prisoners and 351 deserters in civilian clothes. II Polish Corps casualties were again high with 2,150 removed

from the line of which 150 officers and 354 other ranks were killed. In August 1944, while Warsaw rose up in arms, the II

Polish Corps were resting and re-fitting with 886 ex-POW personnel added to the units after re-training in

Palestine (Madja, 1984) or directly replenished at the front (Koskodan, 2009).

Attack on the Gothic Line

The Germans carried out a systematic retreat blowing bridges and mining roads and other river crossing points to slow down

the II Polish Corps advance. By mid August the poles had reached the river Cesano where a strongly defended positions

forced the Corps to regroup and receive fresh supplies. In France the 1st Polish Armoured Division was in action in Normandy

after the successful D-Day invasion. In Warsaw the ‘Rising had commenced. The battle at the river Metauro became the

heaviest II Polish Corps sustained in the Adriatic campaign. The Germans had reinforced the lines with a battalion of

mechanized infantry utilizing powerful anti-tank guns. The initial assault took place on the 18th August and the Germans

retreated behind their main defensive lines so that on 19th August while a fierce battle raged, German units slipped behind the

river Metauro. Accurate artillery fire based upon good field intel coupled to air-superiority denied re-enforcements’

entry into action meant the Germans suffered high casualties and losses in the field with the garrison at Il Vicinato almost

annihilated (Madeja, 1984). The German 278 Division was withdrawn from the field and replaced by 1st Paratroop Division who

had been attached to the Gothic Line. High loss of anti-tank guns severely hampered the defences on the Gothic Line.

II Polish Corps moved into the bridgehead for the attack on the Gothic Line by skirting around the defences at Pesaro. From

25th August the 5th Kresowa Infantry Division fought for four days in difficult conditions and took their prime objective, the

town of Foglia. On the right flank mechanized cavalry units pushed on to the outskirts of Pesaro. It was the skill and speed

of the 1st Canadian Corps that broke the Gothic Line by exploiting lack of time to allow the Germans preparation for the

standoff. Despite the 26th Panzer Division being brought into action, the Canadians were deep into the German lines with

the 1st Carpathian Rifle Brigade inflicting such damage to the German 1st Paratroop Division that it was now battle

ineffective. Clearing up operations continued until 15th September when Monte Altuzzo and Monte Frassino were captured.

With the fall of Monticelli after a fierce battle and Firenzuola captured, the Gothic Line was smashed. II Polish Corps

were removed from the line for 3 weeks to recover.

The II Polish Corps were re-assigned the mountainous areas of the Appenines where roads were few and mule tracks had to be

used to navigate the region. The 5th Kresowa Infantry Division were assigned to attack Monte Grosso and Monte Piero with the

attack launched on 17th October and were engaged in tough defensive actions by the Germans who counter attacked with ferocity.

Autumn rain hampered operations considerably. Monte Crosso was captured on 22nd October and units assembled in a bridgehead

at Strada on the river Rabbi. On 26th October the division captured the heights above Mirabello and Colombo. It had

taken ten days to advance through this mountainous area (Anders, 1949). By the end of October, the 1st Canadian Corps had

reached the river Ronco with the bridgehead being established, but washed out by heavy rain. Germany had committed 18

divisions to the defence of the Gothic Line and constantly switched deployments and by the end of October this sector

including the British 8th Army were facing probably 5 divisions as units were switched to defend Bologna from US 5th Army’s

attack from Firenza. On 1st November the 3rd Carpathian Infantry Division had captured Monte Chioda, Monte Trebbio and

Gattone. By the 8th November units of the 5th Kresowa Infantry Division entered Dovadola and a few days later had

crossed the river Salutare near Pieve and Castrocaro towards Bagnola. Pressure in this sector was reduced when the

New Zealand Division entered Faenza on 16th December. Most observers recognise that the II Polish Corps had fought hard in a

difficult terrain and conditions where mule trains were virtually the only means of supply and mobility. The terrain was

not suited to mechanized operations. For the troopers, the heavy rainfall and slogging their way through mud epitomised

this part of the Italian campaign.

|

|

Appenines

|

Bologna and Ravenna were both strategically important to the Allies and their strategy of containing the Germans and defeating

them in the spring of 1945. Most of the Allied troops were using the mid-winter conditions to withdraw and rotate front-line

troops in order to regain combat strength. Action by the 8th Army supported by the Canadians continued to put pressure on the

German lines defending Bologna down to the Adriatic coast. Germany sent reinforcements drawn from the 710th Infantry Division

sent from Norway. There were discussions relating to the whole of the II Polish Corps being relocated into Germany under one

command (Anders, 1949) and the British 8th Army being redeployed in Yugoslavia. The winter offensive was on hold as the

shortage of troops and munitions curtailed major actions apart from artillery duels and foot patrols in appalling weather

conditions. During the same period, the political scene was turning against the Poles with the conference in Yalta confirming

Stalin’s plans for a divided Europe despite a conference being called by the United Nations to be held in San Francisco.

After re-grouping, the II Polish Corps had the 5th British Infantry Division assigned to them as part of the Lombardy campaign. The II

Polish Corps advanced up the Highway 9 towards Bologna. The 3rd Carpathian Rifle Division would spearhead the attack with

the 5th Kresowa Infantry Division in reserve. On 9th April USAAF bombers caught Polish units out in the bridgehead

(‘Friendly Fire’) with a high level of casualties (Anders, 1949; Koskoda, 2009), nevertheless, the troops remained calm and

achieved their first goal in capturing the heights above the river Senio. The following day the open ground between the

river Senio and Santerno was only broken through after a daring night attack utilizing flame-throwers on tanks

punched through a gap between the 98th German Infantry Division and the 26th Panzer Division. The German units put a tenacious

defence and mounted counter-attacks before the Poles finally dislodged them. Over the next few days’ Polish units gave chase

through Sillaro and the neighbouring canals and engaged the 4th German Parachute Regiment before they were forced to withdraw.

In pursuit the Poles attempted to cross the heavily defended river Gaiano and engage their old adversary the German 1st

Parachute Rifle Division. The 5th British Infantry Division was tasked to swing further north and take the Firenza-Bologna road

to contain German units in Italy and not allow them to escape.

On the evening of 20th April US artillery again caught Polish units in open countryside thinking them to be retreating German

units (Andrers, 1949). II Polish Corps were tasked to take Bologna and the 5th Kresowa Infantry Division had the ‘honours’ of

taking the city. II Polish Corps succeeded in destroying three German divisions in the fight for Bologna (Koskoda, 2009).

On 23rd April 1945 II Polish Corps stood down and for them the war was over. The Allies continued to push the Germans further

back towards the lakes and mountains with strong resistance near the Brenner Pass. Surrender was agreed on 29th April, but it

was not until 2nd May 1945 that hostilities ceased.

|

|

Bologna

|

Additional Resources:

Parker, M (2008) “Monte Cassino: The Story of the Hardest-fought Battle of World War Two”, Headline Publishing Group, UK

Ellis, J (1984) “Cassino: The Hollow Victory: The Battle for Rome January-June 1944”, Arum Press, UK

Hapgood, D and Richardson, D (1984) “Monte Cassino: The Story of the Most Controversial Battle of World War II”, Congdon & Weed, USA

Web Resources:

www2_montecass.pdf

Poles at Monte Cassino

The Battles of Monte Cassino

The Battle of Monte Cassino

Monte Cassino Foundation

Top of Page

|