Operation Wildhorn

(Operation Mosty or Bridges)

Operation 'WildHorn' was a series of planned 'air-bridges' for the movement of specialist war material and infiltration/ ex-filtration of agents and couriers or military personnel from

the AK. Until quite late in the War, air operations were on the limit of operational windows for aircraft and crew. Although 'WildHorn' had been planned in October 1943 release of

aircraft became difficult as the various departments bickered over resources and priorities. Indeed, pressure by the Poles forced a political decision to be given adequate support which at times

appeared to be blocked, side-tracked or simply ignored (PRO/HS4/183) regardless of Poland's contribution to the Allies. The go-ahead came through the Soviet advances in the east and the threat

this would present to the AK and the Underground Government in Warsaw placing the operation on high priority.

'Riposte' Operations (Counterstroke) had been flying out of Great Britain from bases like Tempsford

since September 1943 until July 1944 to support General Rowecki's demands for arms for the AK. It was originally planned to drop 200 tons of material, 800 agents by parachute with

assorted radio and communications equipment and taking into account a 25% loss rate would need 450 'sorties' or 200 night drops by a single aircraft with the balance being achieved through major

collaborative operations.

However, once the Allies had a foothold in Italy, new routes, which avoided flights over Sweden (Route 1) or Denmark (Route 2) opened alternatives, but were still never the less

as hazardous. Route 3 flew over Lake Balaton in Hungary to the Tatra Mountains and then to Krakow in southern Poland, some 600 miles. Although this was a popular route, it was abandoned

after Soviet advances in the spring of '44. Route 4 was further east and flew over Budapest while Route 5 flew via Albania and Yugoslavia to Lwow.

Tadeusz Romer, the Polish ambassador to Moscow had tried to negotiate use of Soviet bases to no avail (Peszke, 2005) and so Special Duties Squadron 1568 moved to Campo Casale,

Brindisi (known as Base 11 or Operation Daybreak or Jutrzenka) and later came under the command of Colonel Jazwinski (Cynk, 1998) and nick-named Jaz by the BLO. Early operations were

compromised through poor weather and performance of equipment (Garlinski, 1969).

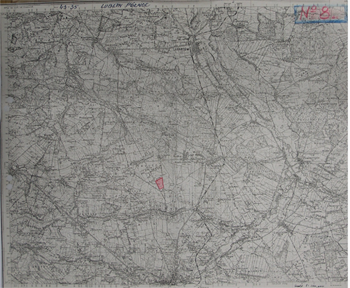

On 15th / 16th April 1944 while Special Duties Squadron 1568 and No.148 Squadron were busy on Riposte missions to Poland, a Dakota FD919 of No. 267 Squadron took off on Wildhorn I.

Fitted with eight additional fuel tanks the Dakota was piloted by F/Lt. E.J. Harrod (RAF 267 Squadron) and navigated by F/Lt. Boleslaw Korpowski (PAF No.1568 Flight) and took off for

Belzyce (code name Bak) 22 miles from south-west of Lublin (Cynk, 1998; Garlinski, 1969). On board were two couriers: Captain Narcyz Lopianowski (codename "Sarna" after

his favourite horse) and Lieutenant Tadeusz Kostuch plus dispatches. They were also ordered to pick up five passengers mainly from the government delegatura that included the AK

Deputy Chief of Staff, General Stanislaw Tatar. The 'manifest' for the return flight included Lt. Colonel Ryszard Dorotycz-Malewicz, Lt. Andrzej Pomian (Information and Propaganda Bureau),

Zygmunt Berezowski (Nationalist Party) and Stanislaw Oltarzewski.

At the time of planning the Wildhorn Operations relations with Moscow were strained. Ciphers (PRO/HS4/180) indicate the operation should continue without Soviet consultation or

'approval' and the planners would have to estimate the risk based on both Nazi and Soviet strength in the area, from AA flak and night-fighters together with the landing ground conditions.

Preparation for Wildhorn had started in early 1943 with Churchill's approval where negotiations between the Polish IV Bureau, the Foreign Office, Air Ministry and War Ministry discussed

not only the political importance, but also logistics with SOE planners. It was originally proposed to use a Hudson III bomber being adapted for the operation. Doubts were raised over its suitability

and insufficient research over landing grounds added to delays as the night operational window closed as time drifted into spring/ summer weather of 1943 where the bomber would need over ten

hours continuous night and a good moon to assist landing.

Lt. Colonel H.B Perkins also had some doubts over the effectiveness of pick-up operations to Poland despite their success rate in France and Lt. Colonel Dorotycz-Malewicz (Hancza of

the 'S' Section of Special Bureau) suggested the relocation of the landing grounds to Radom or Kielze area. Even Lt. Colonel Trefford of Force 139 joined in with the bickering and affray by

suggesting that as the Eastern Front stabilized, the AK would be important in the overall strategy for ending the war and communication via special runs would speed the delivery of important

documents or agents. Even the crews designated to the operation had concerns over the type of aircraft and landing grounds whose conditions and layout did not favour a successful landing with a

tight turnaround time and take-off. An alternative landing ground in Slovakia was suggested, as it was only a 150-mile hop to alternative designated landing grounds near Krakow. For the flight

crews of 267 Squadron an unarmed Dakota was no worse than a Halifax with only a rear gun turret. Lt. Colonel Ryszard Dorotycz-Malewicz (Code name Hancza) agreed to the final route

and landing ground on 9th November 1944 as pressures were mounting to bring out the Polish delegation.

The Dakota landed on 16th April 1944 in a stubble field down-wind on a shortened landing strip without suffering damage (PRO/HS4/181) and represented the culmination of five months intense

planning. Unfortunately, two days before the operation the district was flooded with German units and the AK set up a protective perimeter around the LG and fought for 40 hours and lost

42 soldiers to keep the site secure. Despite the soft earth and trees bordering the site, the Dakota managed to get airborne and return to Brindisi.

Source: PRO/HS4/180

The exchange of passengers had taken between six to ten minutes and the manifest showed they had picked up General Tatar, Deputy Chief of the AK (code name Tabor; Turski);

Lt.- Colonel Ryszard Dorotycz-Malewicz (code name Hancza) a 'Special Forces' operations and communications expert; Lieutenant Andrzej Pomian of the Information and Propaganda

Bureau of the AK; Zygmunt Berezowski of the Nationalist Party and Stanislaw Oltarzewski of the government Delegatura (Cynk, 1998; Garlinski, 1968; Nowak, 1982).

However, the passengers were not accurately recorded on the original manifest and this upset 'Whitehall circles'. A cipher dated 19th April (PRO/HS4/180) relayed the possibility the manifest

covered the true identities for security purposes. For example, Lt.- Colonel Ryszard Dorotycz-Malewicz travelled as 'Adamczewski' while Stanislaw Oltarzewski travelled as Lieutenant 'S' and

Zygmunt Berezowski travelled as Captain Marabut. The non-disclosure of identity caused such upset that a further two inter-departmental reports were written to 'smooth ruffled feathers'. It must

be remembered the Polish Government in Exile had a degree of autonomy and its own cipher system effectively shut out various factions like the Foreign office and MI6 (SIS). To confuse the

researcher, the internal report uses code names for the passengers without rank leaving the report more amusing to read many years on.

The party flew onwards the next morning via Gibraltar and landed at Hendon airport in north London. The party were interned and interviewed by various intelligence departments and the Foreign

Office who misunderstood the significance of General Tatar's visit in the prelude to the Warsaw Rising (Nowak, 1982). As a consequence major changes were implemented within the VI Bureau to

command structures within field operations and communications.

Operation Wildhorn II

Operation Motyl or Butterfly

Following the success of Wildhorn I to establish an air-bridge and demonstrate to a variety of organizations, particularly the Foreign Office in the possibility of these flights regardless of the

distances, Wildhorn II was scheduled to land at Zaborow near Tarnow. The site was confirmed in a cipher on 8th May 1944 would use site No.4 with a W/T operator within the vicinity

reporting weather conditions (PRO/HS4/180). With pre-arranged identification codes and flare-path, details for the landing ground which measured just 300 by 1000 metres could only be approached

from the north-west with the pilots briefing indicating a deep ditch by woods known as 'Zabawski Row' would be the only hazard. Only the poor spring weather held up operations.

The flight took off on a moonlight night 29th May in a Dakota piloted by Michael O'Donovan of No.267 Squadron with P/O Jacek Blocki acting as co-pilot. Michael O'Donovan was a South African officer attached to the squadron whose gallantry earned him the Polish order Virtuti Militari, 5th Class on the 30th June 1944 (London Gazette).

Also on board were two passengers: Lt. General Tadeusz Kossakowski (specialist in armoured warfare) and Lt. Colonel Romauld Bielski (sabotage expert) plus stores (Garlinski, 1969). The flight was escorted by two Polish Liberators part of the way of its

journey (Cynk, 1998). The Dakota landed on a disused German field without incident and within six minutes had taken off with three passengers on the manifest: Group Captain Roman Rudkowski

(chief of air-intelligence of the AK), Major Zbigniew Leliwa (code name Kedyw) and Jan Domanski of the Peasants Party. The flight was deemed to be a great success.

The British halted flights to Poland in June 1944 with aircraft from Flight No.1586 diverted to other duties in northern Italy and the Balkans and against the wishes of the PAF and AK.

Tension was running high amongst Flight No.1586 when Group Captain Rankin ordered the Polish crews to fly on four to five consecutive nights with Squadron Leader Arciuszkiewicz refusing the

order and was grounded (Cynk, 1998). Rankin was replaced by Group Captain Woodhall and relations improved and operations to Poland resumed in July 1944 with the flight being re-equipped with

three Halifax bombers and two Liberators'.

Campo Casale (Operation Daybreak or Jutrzenka), Brindisi May 1944

This is the location of anchor one

Operation Wildhorn III

Background

Germany had been experimenting unsuccessfully with rockets since 1909 when Krupp's in Essen had bought the patents from Lt. Colonel Baron Wilhelm von Unge and after 1932 scientists began

working on behalf of the Lufwaffe on liquid fuelled experimental rockets. In the early 1930s Werner Von Braun joined the project on what became known as the Vergeltungswaffe

(Retaliation) weapon and indeed, Von Braun became synonymous with these weapons. The team also included the engineer General Walter Dornberger. Peenemunde was a heavily wooded island at the

mouth of the river Oder, not far from Szczecin and in 1936 this sleepy island would be converted to the testing ground of

Hitler’s most secret weapons.

As the V weapons project moved from experimental to pre-production the demands on resources, particularly human forced the Nazis to consider forced and slave labour to fill gaps in the stretched

war economy. In the spring of 1942 RAF air raids were beginning to make an impact upon the German war effort with production factories being regularly hit. Speer was ordered in December 1942

to prepare plans for the production of 3,000 rockets per month (Garlinski, 1978).

The Organization Todt recruited labourers to work on roads, defences and airfields for the Reich. It was the infiltration by the AK of the Organization Todt that enabled spies and

couriers to obtain, analyse and report on the technical developments of the Nazi's with great effect. By twist of fate Antoni Kocjan (code name Korona) had been released from Auschwitz

and joined the Bureau of Economic Studies within the ZWZ (Garlinski, 1968, 1978). The department known as Arka was working on the details of V weapon secrets whose information

had trickled in from agents working in the Szczecin area when an unconfirmed report via Denmark indicated a large rocket had been fired with a range of 300km somewhere on the Baltic coast.

Sightings of a plane with stumpy wings and an engine noise not know were also being reported.

In April 1943 the secrets of Peenemunde had been smuggled out of Poland in a brief case containing film and plans of the site to a safe house in Vienna via Switzerland en-route for Britain by

courier Wladyslawa Macieszyna (code name Slawa) who was a few days later arrested and tortured. The AK had implanted into Peenemunde two agents working for the intelligence

group Lombard (Garlinski, 1968, 1978). Jan Szreder was an engineer and Roman Trager was an NCO with the Wehrmacht of Austrian origin and operated under the code

name Furman. Similar reports were coming from French and Belgium sources particularly from a Luxembourgoise worker, Pierre Ginter who had smuggled out plans of the weapons and

also the location of AA batteries protecting the site.

On 17 - 18 August 1943 (Operation Hydra) the RAF sent approximately 596 bombers to drop 1,800 tons of bombs on the installations and experimental launch sites including the liquid

fuel stores. Some key German scientific personnel were killed and Von Braun had managed to survive the hail of HE and phosphorous bombs. Some bombs fell short and killed somewhere between

500 - 600 workers, however this figure still remains in dispute. Certainly the raid was a success as the production of V1 production was delayed by six months and the V2 for

nearly a year (Davies 2003, Garlinski, 1968, 1978).

In the late autumn of 1943 reports were being received by the regional HQ of the AK in the Krakow region that major repairs to roads and a railway branch line from Kochanowka together

with new installations being built at an SS training camp and artillery range in the vast forest sandwiched between the Vistula and San rivers at Blizna, near Mielec. In December 1943

a report reached Colonel Iranek-Osmecki (code name Makary or Heller) head of AK intelligence that a test firings in the Blizna area had created numerous craters with special

clean up crews scouring the countryside and removed every shred of evidence. Plans were made to storm the site with Lieutenant Stachowski, commander of the AK in the Debica area to lead the

attack or attack rail transports carrying the weapons (Garlinski, 1968).

On 20th May 1944 a V2 rocket landed in the marshes at Sarnaki on the river Bug, 50km from Siedlc in eastern Poland and had failed to explode (Garlinski, 1968). According to

Garlinski (1968, 1978) the 22nd Infantry Regiment of the AK collected the rocket in carts after hiding it in the marshes and then hid the V2 in a barn at Holowczyce-Kolonia 5km away. Jerzy

Chmielewski (code name Raphael) together with Antoni Kocjan (code name Korona) was order with a team of engineers and scientists from Warsaw to dismantle and log all the

parts - some 25,000. It also included a new type of guidance system that had not seen before. An analytical report was produced with diagrams, photos and chemical analysis of the propellant. It

also considered the construction of a deception transmitter station inside Poland to deflect the rockets away from their intended targets (Garlinski, 1968, 1978).

The Operation:

London came under attack from the V1 rockets on 13th June 1944. The Allies began to put great pressure upon the Poles to release information about the fuel and guidance system as London was

now daily under attack and it was also D+7 with the invasion of Normandy had partially stalled at Caen. In Italy, Flight No.1586 had suspended flights to Poland and was busy supporting Italian

and Yugoslav partisans with their commanding officer about to be suspended.

Flights from Brindisi resumed on 3rd July with 5 Polish and 7 RAF crews flying Halifax bombers. The operation was designed and co-ordinated by Major Jazwinski who struggled to contain his

despair over the imbalance of flights between northern Italy, Yugoslavia and Greece to the mediocre numbers allocated to Poland (Nowak, 1982).

On 25th July a Dakota V of no. 267 Squadron left Brindisi piloted by F/Lt. S.G Culliford. The navigator was F/O K. Szrajer from No. 1586 Flight who was the operations commander and they

were escorted part of the way by a Liberator (Cynk, 1998). On board were 19 suitcases of specialist equipment accompanied by Captain Kazimimierz Bilski, 2nd Lt. Leszek Starzynski, Major

Boguslaw Wolniak and the courier Lt. Jan Nowak (Garlinski, 1968, 1978; Nowak, 1982).

The chosen landing site was again at Zaborow near Tarnow due to expediency of time as the Soviet Army was fast approaching the River Vistula and an experienced reception crew used to

tight landing conditions and signals with S-Phone communications made the site viable. The ex-filtration of the V2 parts was the priority and all other passengers boarded according to priority with the

risk of being left behind if the plane could not take off (Garlinski, 1968). The take off proved extremely difficult, as the Dakota's wheels had sunk into the soft ground and hydraulic brakes had jammed.

With two German AA batteries housed in the adjacent village (Cynk, 1998) we can assume for both the ground and flight crew the moment posed great danger and the decision to abort was considered

before the ground yielded on the last attempt.

On board were V2 parts, drawings, diagrams and over 80 photographs in the company of Lt. Jerzy Chmielewski (code name Raphael); Jozef Hieronim Retinger (code

name Brzoza, Salamander); Tomasz Arcieszewski of the Socialist Party who had orchestrated the Council of National Unity and presidential candidate; 2nd Lieutenant Tadeusz Chciuk,

apolitical courier and the last member of the party was Czeslaw Micinski (Cynk, 1998; Garlinski, 1968, 1978). On landing at Brindisi Arcieszewski, Retinger and Chciuk flew to Rabat in Morocco to

meet Premier Mikolajczyk who was en-route for Moscow. Lt. Jerzy Chmielewski and Czeslaw Micinski arrived in London on 28th July 1944 and the precious cargo handed over to the Polish General

Staff where the coded documents were translated before being handed over to the British Crossbow Committee.

The first V2 rockets dropped onto London during 18th September 1944. Since late August, Montgomery's 11th Armoured Division had been moving north along a coastal corridor in northern France

and crossed the River Somme. The 1st Polish Armoured Division (The Black Devils) supporting the Canadian's had reached Abbeville and were in high-speed pursuit of the retreating

German Army. Meanwhile, the Dutch underground had identified V2 mobile launchers located in the town of Serooskeke within the area of the Walcheren. It had been previously assumed that

General Montgomery's planned dash to the Ruhr via Holland had been strategically altered due to lines of supply from Dieppe being stretched and the need to secure Antwerp was of secondary

importance, however, this was not true. General Montgomery maintained the need to liberate Holland via Market Garden. This necessitated change in plan was to be a strategic disaster

as the need to remove the V2 threat to London and cleanout the now heavily defended pocket at Walcheren and secure Antwerp's port was dismissed.

Wildhorn IV due to take place in September, but delayed until 15th December 1944 when weather conditions suddenly changed and the flight ordered to return. The last Riposte

flights had been on 30th July 1944 and had successfully parachuted 285 Special Force soldiers (Cichociemni) into Poland. Three had drowned in the North Sea and three died when their plane

crash-landed in Poland. Three died when their parachutes failed to open and many died on the battlefield.

Jozef Hieronim Retinger (code name Brzoza, Salamander) was an intelligent and devout catholic whose activities during the war still remains a little clouded in mystery. Born in Krakow in 1888 and educated in the Sorbonne in Paris, Retinger had a controversial if not an almost 'swashbuckling' career ranging from being connected to the Berber revolt led Abd-el-Krim against the French occupation in north Africa during the 1920s through to a major role in the defeat of an anti-catholic revolution in Mexico where he set up a trade union. Jozef Retinger met Sikorski in France during the pre-war era and was a special envoy to Churchill and the Vatican (Eminence Grise). He was also the secretary to the Polish Council of Ministers and a close aide to Sikorski.

Sent to Poland on 3rd April 1944 on a Riposte mission from Italy, he parachuted into Poland at the age of 56 years old despite his instructors deeming him unfit to jump. The mission was so secret he wore a mask to disguise his features (in report from EUP/PD/5104 in file PRO HS4/240/112089). On landing he injured his leg, but managed to complete his mission. He entered Poland under the cover or false particulars of one Captain Edward Albert George Paisley born in Birmingham, England on 22nd October 1898 (PRO HS4/240/112089). The initial operational code name was DALBY under the operation code DENHAM (his code name was later changed to SALAMANDER). He used special ciphers and W/T set provided by the VI Bureau. He also carried on him $10,000 US and $125 US in gold to fund the trip. Despite being close to Churchill and other leaders, Major Hazell MBE described Jozef Hieronim Retinger in an internal memo to Frank Roberts in the Foreign Office as "the man who looks rather like a monkey" (and similar comments in other internal memoranda) (PRO HS4/240/112089) and perhaps this sums up the Establishment's attitude towards Poland.

His return to Britain was seen almost as important as the V2 secrets hence the prioritization of the return manifest for the Dakota by Colonel Ryszard Dorotycz-Malewicz (code name Hancza). Retinger was seriously injured when a cart carrying him to the landing strip fell into a ditch leaving him partially paralyzed with 2nd Lieutenant Tadeusz Chuick eventually carrying him to the plane. He had socialist leanings in his early career and after the war was linked to the Bilderberg Group who have been linked by conspiracy theorists to global domination by multinational companies. Jozef Retinger was an ardent supporter of a United Europe and his controversial views remain widely debated to this day. He died in 1960 of cancer in his adopted London.

Operation Wildhorn IV & Operation CATFISH

Background

On 30th November 1944 the instructions for WILDHORN IV were sent to 267 Squadron and Force 139 confirming the details outlined in a planning meeting held on the 16th November. 267 Squadron with crew from 301 Squadron would do a pickup operation planned for 2-3 December or first available night due to the weather conditions and the ground being saturated.

The landing ground coordinates were given as 511730N and 200130E, however these place the LZ at Klew near Zarnow in a forest rather than Nowy Targ. The route was to be vectored from Brindisi, Szeged in Hungary, over the Tatra Mountains towards the river Vistula to the village of Nowe Brzesko before turning to the LZ with instructions to return by the same route. The pick-up was for 5-6 POW's that additionally included Wicenty Witos (politician) and Sgt Ward (RAF). Sgt. Ward had escaped from a POW camp near Lissa (today Leszno) in 1941 and after seven days on the run had been put in touch with the Polish underground (ZWZ) through a priest. He was moved to Warsaw where he prepared BBC reports for dissemination and broadcasted valuable reports on the current state of the Warsaw Rising and the actions of 17th AK Division. These were often published in the Times newspaper. Despite being wounded twice and surviving a lengthy interrogation by the NKVD (Davies, 2003; Kochanski, 2012) it was planned to get him out on the flight.

The operation became more marginalised due to the Soviet advances and also a notification on 27th December by Colonel Rutkowski that German 'pacification' (ethnic cleansing) in the area and poor state of the LZ meant the operation may be delayed until the 2nd January or later in the spring of 1945. A cypher dated 19th January 1945 indicated a hope the operation would go ahead that night, however the Soviet advance within the area despite being 'fluid' in the control and occupation in the area made the attempt politically sensitive. A later cypher confirmed no contact with the reception committee had been made and the weather impossible for a landing. It was assumed the LZ had been over-run. A cypher dated 21st January 1945 informed PUNCH that the reception committee had not been in contact and it was around the 19th January 1945 advanced units of the Soviet forces had entered Nowy Targ and Zakopane. Likewise, operation CATFISH where 2 Dakotas were due to pick up escaped British, American and Polish aircrews under the protection of the AK in the Nowy Targ area was cancelled.

Tarrant

Rushton Airfield

http://www.tarrant-rushton.ndirect.co.uk

or email: andrew.wright5@virgin.net

Women of the SOE

http://www.64-baker-street.org

The Warsaw Rising

http://www.polandinexile.com/rising.htm

The Polish Air Force - Pictures with Questions

http://polishwings.bravepages.com

Top of Page