|

Campo de Concentration de Miranda de Ebro

August 1941 – March 1941

Click here for the story of Władysław Popiołek experience of the camp

The Franco-Spanish border August 1941

In August 1941 my friend and I managed to reach Hendaye, on the Franco-Spanish border, and considered our options to get across the River Bidassoa. We waited a few hours, watching the guards’ huts, and the flowing river, and started to swim at the point where there was a small island (the Ile de Faisans) in the middle. The water came up to our chests, and although my friend was a good swimmer, I was not. One of the border guards must have heard us and we arrived at the far bank to find him pointing a loaded gun at us. We climbed out and stood on the bank, dripping wet and miserable.

We were taken to the guardroom, and searched. They took the 700 francs that I had saved for the journey. We were then taken to a house built against the hills, and shut in the cellar. We were in Irun, Spain, cold, wet, miserable and hungry. There were three other prisoners, one bulb lit the cellar, and the bed to sleep on was just wire mesh. The next morning we had food, but I couldn’t eat most of it and gave it to the others who were very hungry. At this point I was still hopeful that Spain, being a neutral country would send us on our way.

One more night passed in the same way, and then on 6th August 1941, two guards arrived with another Polish prisoner. We were then chained together, with guards holding the ends of the chains, and taken through the town to the station where we boarded the train to Miranda, when we were given bread and water. It was normal for The Guardia Civil to escort prisoners through the streets in this way, but it was a shock to us.

Arrival at the Camp

At Miranda they took us to the camp, where over the large gate were the words “Campo de Concentration de Miranda de Ebro”. There were stone walls topped with high barbed wire, a walkway for the guards and observation posts behind the wall overlooking the whole camp. This camp, which has since been demolished, was built under the supervision of the Germans to house the prisoners of Franco in the Spanish Civil War. Wysocki in his book ‘Urge to Live’ tells that after the “Liberation” of Miranda de Ebro by the Franco forces in the Civil War, 150 Republicans were executed in the place where the camp was later built. Women and children were whipped through the streets. There had been many atrocities on both sides, and there were still Spanish prisoners in the Camp during our imprisonment there.

We were handed over to the NCO on duty and our details taken down. We declared ourselves to be Poles, and were handed over to a ‘Cabo’ (a former prisoner, in charge of a barrack) who allocated us an area of a bare wooden floor about 2m x 2.5m between the three of us. It was very warm in the day, but cold at night and we had no mattress or pillows, just one thin blanket. It was extremely difficult to keep clean and free of lice and fleas. About halfway through my stay the head of the Polish Group, Captain Snarski, negotiated to have our underclothes washed and boiled by an outside laundry, which whilst it did not get rid of the bedbugs, helped somewhat.

Władysław Popiołek, Miranda de Ebro

Daily Life

Every morning and evening all the inmates had to attend the ‘bandera’ and shout “Aviva Franco, Aviva Espana”. We all had to stand to attention, with arms raised, to honour the Spanish flag going up the mast.

We worked at moving stones from the nearby quarry to the river. A bulldozer today would manage it in a few hours, but it took us a back breaking year. Stones were put into baskets and two prisoners would each take a handle. Wood had to be unloaded from the railway wagons, for cooking, and the guards would beat us if this was not done quickly enough. Beatings and whippings were commonplace, and injured prisoners were often thrown into solitary confinement. There were accidents and several of the prisoners become mentally ill.

As hard as our life was in the Camp, we felt even sorrier for the Spanish who were kept there, and treated worse than animals. All over Spain people lived in extreme poverty, but to watch these prisoners being so ill treated and searching the dumps and rubbish heaps for scraps to eat was unbearable. The very young, and the very old, priests who refused to recognise Franco, anyone who crossed the regime’s path, all of them squeezed into barracks with wooden floors and no blankets.

There were many nationalities in the Camp as well as the Spanish. I was, however, in a community of Poles, who had arrived from various directions, and who still wanted to fight against the Nazis and return to Poland. When I arrived there were about 270 of us, but this rose to about 1000. The Poles had organised themselves from the word go and this helped, to be part of a large group.

Food

The food was little and very bad. Aged eighteen I dreamed only of having enough bread to eat. On Franco’s birthday and on a few other special days we were given such things as paella, which tasted delicious to me.

The normal ration was a small piece of bread in the morning with weak coffee. At midday we had a ladle of indifferent ‘slop’ and the same for supper. The worst for me was when the ‘slop’ was based on the shucks of broad beans, and despite being terribly hungry, I just could not stomach this. We were given a few pesetas from the Polish Legation in Madrid and some free cigarettes. As I did not smoke I gave them to my friends. The pesetas could be spent at a rough and ready ‘canteen’ which had large onions, wine and on very rare occasions a few bocadillos (small bread rolls with perhaps a little cheese in them) for sale. I never managed to buy one in the whole time I was there.

Hunger Strike

In an attempt to get the conditions of the Camp improved, the Poles organised a hunger strike. It began on January 6, 1943 when all Poles (about 700 of us) refused lunch. The Czechs and Yugoslavs then followed suit and in the end all the other nationalities joined in, except for the Spanish prisoners. I can remember becoming very weak. A total of around 4000 eventually took part. According to Wysoki, the first prisoners to collapse from hunger were the French, then the Belgians and then the English. I recall the strike as lasting about a week, after which we were allowed to get some extra rations in the form of tinned food from the Polish Legation in Madrid. I understand the strike ended following negotiations with the British Ambassador and others who came from Madrid to visit the camp authorities. It helped that there had recently been military successes on the part of the Allies. So we were promised improved camp conditions.

Studies

One afternoon I was sitting outside one of the barracks with 2 or 3 friends when a drunken Polish merchant sailor came round the corner and started to attack one of my group with a broken bottle. I tried to reason with him, but my intervention ended up with me having a cut head and being taken to the acting Polish doctor. He was Leon Slupinski and he had an assistant called Sgt. Kanski, who later joined the Polish paratroopers. Leon was a medical student from the University of Wilno who served in the Karpathian Brigade, fighting at Narvik alongside the French Foreign Legion. This Brigade was withdrawn from Norway and sent to Brittany after the attack on France on 10th May 1940. On its arrival the Germans were not far away, and Petain had surrendered France and so Leon made his way down to the Mediterranean coast mostly on a bicycle stolen from Germans who had confiscated it from a civilian. For his bravery in Norway he was decorated with the ‘Virtuti Militari’, the highest Norwegian medal and also the Legion d’Honneur. Leon talked to me that day and eventually became the older brother and friend I had never had.

Leon suggested I take lessons in Polish, Polish history, literature and Maths, amongst other subjects. The Poles, whose numbers in the camp had grown to around 1000 at this time, organised lessons which I attended with enthusiasm, and passed courses equivalent to the old school certificate. To some extent conditions started to improve and we were allowed to play football, basketball and running.

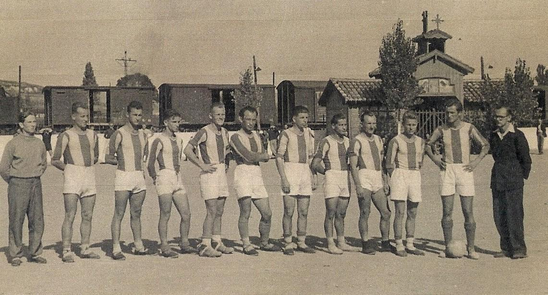

Football team end 1942-beg 1943 : Władysław Popiołek 4th from left

The little chapel is in the background

Escapes

There were some escapes. One of the officers I knew, Lieutenant Parylak, escaped through a tunnel that he and others dug from the little chapel. He reached the Polish Legation in Madrid and others were planning to try and escape this way. One Pole, Lieutenant Stanisław Kowałski, was shot by a Spanish officer whilst escaping from the camp on September 4th, 1941. He had been the one who translated the ‘Hoja del Lunes’ every Monday which kept our group connected to the outside world, and he was sadly missed by our group.

Release

Meanwhile outside the Camp, the fortunes of war were changing. It no longer suited the Franco regime to upset the Allies by keeping their nationals imprisoned. Word came through that we were to be released in the spring of 1943. It was agreed that we were to be released in batches of 100. I was given some clothes from an American charity, and a passport, and on 21st March 1943 I and 99 other Poles marched through the gate and onwards to help in the war effort. First though, we went to the cemetery and paid our respects to Lieutenant Kowałski.

Visit to Miranda in 2006

The river Hendaye is still the border between France and Spain, although blocks of flats and houses, and a tarmac footpath winds along the bank.

The French side of the Bidassoa, showing the Ile de Faisans (Isla de los Faisanes) in the middle of the river

I went back to the Miranda area to see what was left of the infamous Camp. There were quite a few Basques in the Camp when I was there and they had a lot of sympathy for us at the time. So it was when I returned and described my quest to people living in Vitoria and Miranda, trying to find what remained of the camp. Very little remains, a small stretch of railway track hidden in an industrial estate, and a small plaque that is covered in graffiti.

Remains of rail track, Miranda de Ebro Camp

Graffiti covered and broken, the memorial to the Camp

The area has changed beyond recognition, and the mound where prisoners’ bodies were heaped and covered in quicklime has of course disappeared now. An industrial estate has grown up over the space that the Camp occupied. However the local people still remember, as do all of us who had the misfortune to pass through it.

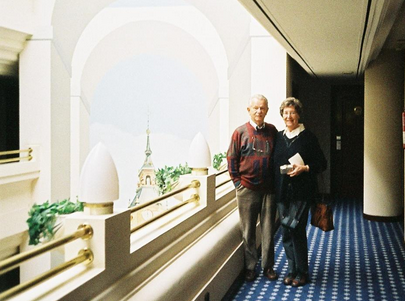

My wife, daughter and son-in-law came with me on my trip back to Miranda de Ebro. I am pleased to say we all ate very well indeed and stayed at a beautiful hotel.

Audrey and Władysław Popiołek, Vitoria, 2006

The following comment has been sent in by Irene Ford that gives a bit more of an insight into life at Mirando de Ebro.

My name is Irene Ford, nee Bednarz. My father is Marian Bednarz and he was at the camp. I believe my brother, Dennis Bednarz has recently been in touch. I read the account of the camp with great interest. One section reminded me of a story my father told me when I was young. He told of the daily salute to Franco. He said, with great glee, that the Polish prisoners would substitute a Polish swear word for the name Franco. It was nearly identical and the Spanish guards never realised. They would say ‘sranco’ not Franco as they made the salute. (Not sure of

the spelling). I wonder if anyone else remembers that?

Polandinexile.com: Can anyone assist or help us with this?

|