|

'Memories of Siberia'

by

Olczyk, Roman

1919 - 2003

The following story has been kindly donated by Maria Vanderstichel. All copyright belongs to Maria Vanderstichel and permission is required for any part to be copied. The Vanderstichel family reserve all rights to these materials for any publication including electronic media.

Roman finally settled in Belgium and sadly passed away on 24th December 2003 in Ottignies, near Louvain famed for its university. The following story is Roman’s account of his war, bravery and odyssey through the war years. As a cadet officer he earned his parachute badge in Italy (no.4522) and later became attached to the Commander in Chief’s special training unit for the Cichociemni in Italy of which little has been documented in the public domain.

Roman Olczyk trained as a soldier in the Cichociemni an elite special force during the war and was transferred to the II Polish Corps and fought a distinguished war in the Italian campaign.

Soviet liberation

In June 1939, at the age of 19, I finished secondary school. I gained some experience in a bank in Brześć on Bug (now Брэст in Belarus). I am living with my parents and I am looking forward to the future. Brześć a town in the Poleski vojevodship and it lies between the rivers Bug and Muchawiec and has a population of 35,000.

It is becoming more restless in Poland because the Germans have invaded Austria and the Sudetenland. Currently they have started demanding territory from Poland. They are demanding a free passage through Poland from West Prussia to East Prussia. Poland does not agree to this. On the 1st September 1939, the Germans cross Poland’s border without declaring war. They bomb Warsaw and other larger cities; they kill many thousand civilians. I, together with my older brother Czesław am called up into the army. I was detailed to support service in the fortress in and my brother Czesław to his regiment, which was en route to the front. Poland defends herself sustaining great losses but she cannot match Germanys modern armored divisions and air-force. Our army still has cavalry regiments and only a small number of modern weapons. During two weeks the Germans occupied nearly three-quarters of our territory. Warsaw still defends herself, together with a few other places including the fortress in Brześć.

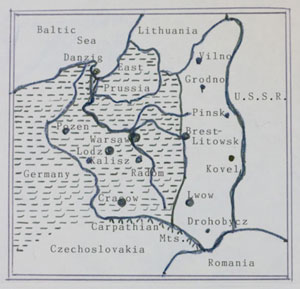

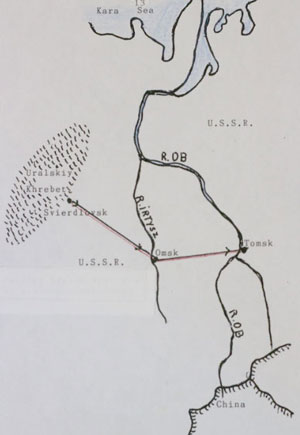

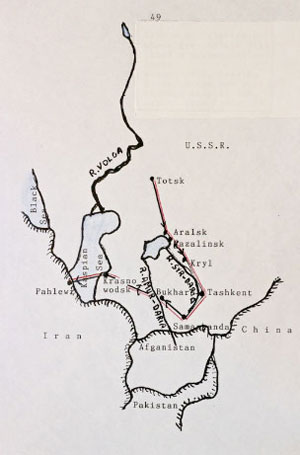

Roman’s hand-drawn map September 1939

In the meantime something happened which nobody expected. On 17 September 1939 the Soviet Army entered eastern Poland. Leaflets dropped from aircraft informed us that the Soviet army had come to protect the proletariat from their masters in Poland. After several days the Polish army laid down its arms. The Germans took one part of the army prisoner and the other part was taken prisoner by the Soviets. A new border was agreed between the two invaders. The river Bug was currently the border and Brześć was a part of Russia.

Roman’s hand-drawn map September 1939

post-Soviet invasion

My brother and I returned to our parent’s home. In October 1939 my oldest brother, Bolesław, returned with his wife. He was in the Polish police force in Lwów. In our town notices went up telling people to get back to work. Our farther was a conductor of the railway orchestra and got work. My brother Bolesław got work in the hospital. Brother Czesław, a forester by trade, returned to work in the Białowieska forests. I received work in a drawing office, planning houses in our town. After a while the Polish currency was replaced by Russian rubles. All goods disappeared from the shops in town. The Soviets opened a few shops in which you could buy bread, vodka and sometimes flour in the morning. To buy bread in the morning you had to queue all night. Monthly wages were between 200 – 300 rubles. A kilogram of meat called “rabanka” (pork meat with fat) cost 150 rubles. We bought vodka and sold it to the Soviet soldiers for a higher price to help bring in more money. There were also a few state restaurants, which served soup with bread and vodka with pickled gherkins and pickled herring. You could trade on the streets; you could buy watches, leather goods, lingerie, silk stockings and cigarette lighters. Soviet officers were the best customers because they had lots of money and they paid higher prices. The Soviet NKVD were busy catching and imprisoning: commissioned and non commissioned officers, police and all those who were in the Polish services. Our fist Christmas of 1939 and the New Year 1940 passed under Soviet occupation. Families usually lived together and were very close, because we knew what was awaiting us from two age long enemies currently representing fascism and communism.

Please be seated

In the first days of February 1940 there were rumors that most of those imprisoned had been deported to Siberia. Currently the Russians are going to deport all Poles and replace them with Russians. I received a letter from my brother, the forester from Białowieska, asking me to visit him because he had something to discuss with me.

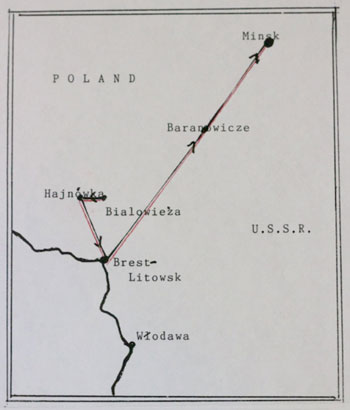

The winter of 1940 was very snowy and severe. I left for Białowieska by train on the 9th February to see my brother Czesław. I arrived in Pruzany where I slept over at a friend’s house. Next day I traveled to Szerszewo village by sleigh and from there to Białowieska I went to the forest inspectorate where my brother worked and lived. There were many sleighs around with armed Soviet soldiers. There were many people with children and packages on the sleighs. A Soviet officer asked me what I want here? I answered that I came to visit my brother. What is your brother called? I answered – Olczyk Czesław. The officer looked at a list he held in his hand and said: ‘that’s good, please sit in the sleigh with your brother’. After awhile I saw my brother on the sleigh with other people looking very sad. All around I could hear crying and wailing. I understood straight away what was happening. They were deporting Poles to Siberia. Around midday a column of sleighs full of people surrounded by Soviet soldiers made its way to the nearest railway station at Hajnówka. At the station there was a long freight train and around it many people with packages. We were told to take our places in the wagons. So, together with my brother and his friends we occupied the first wagon. I understood what my brother wanted to see me about. It was the 10th February 1940, well remembered by many Poles from the eastern borderlands. My brother was totally broken both morally and physically, just like all the others. I thought of how I could inform our parents about our fate. I knew that the train had to pass through Baranowicze on the way to Russia. At a station, during one of our stops, I saw a train driver I knew, taking his train to Brześć n/B. He lived in the same building as my parents. I gave him a note informing my parents what was happening to us and that in a day’s time we will be traveling through Baranowicze. Indeed, our train stopped in the sidings at Baranowicze. Next day our dear mother came to our wagon crying, carrying packages containing underwear, clothes, blankets and food. My brother was laid up ill, but he came out with me to our mother. I could have run away, but because my brother was ill I did not know what to do. I talked with my mother and I asked her – should I run or should I stay with my brother? My mother cried and did not answer. My brothers friend said – your mother would never tell you what to do, you have to decide for yourself.

Today, being 80 years old and writing these words I cannot hold in my tears. My brother was always different from me; especially physically he was not very tough. He was ill so if I ran away he would not manage by himself in such difficult circumstances. All the other people in the train were families (husband, wife, and children). I decided to stay and help my brother. After two years I was convinced that I did the right thing. Our mother asked the Soviet officer: where are they going? The officer replied: to a different region in the Soviet land, where they will live well. Our mother kissed us but could not turn away to go home to our farther. The state that our mother and we were in is impossible to describe. For a few days after my brother and I could not eat or talk normally.

The journey to another part of Russia

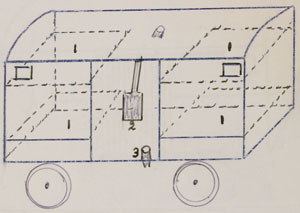

Carriages in which we travelled were normally used to transport goods. Inside were bunks to sleep on. The bedding was straw, on of which we slept, ate and had conversations. In the centre of the carriage stood an iron stove with a pipe going out of the roof of the carriage. Near the stove stood a box with coal, which we filled when stopping at stations. By the door was an opening in the floor of the carriage, with a pipe to relieve oneself. The pipe constantly froze and it was necessary to defrost it with hot water. We gathered snow into buckets, we placed them on the stove and then we poured hot water into the pipe. This was the reason for the stench in the carriages.

Roman’s hand-drawn diagram of the Soviet transport carriage

In every carriage there were at least 30 people. Before moving off, Soviet soldiers (bojcy) would close the door in every carriage from the outside. We had to seal the upper little windows and door so as not to freeze during the night whilst asleep. It was warm around the stove, but further away it was cold. We slept in clothes and hugged each other to keep warm. In the carriages people constantly sang religious songs and wept.

After several days we passed the old Polish border and we entered Russia. We found out that we were travelling along the main railway line towards the large city of Minsk. There was more snow and more severe frosts. Draughts of cold air coming through the door and windows caused us great problems. We kept the stove burning constantly and every adult had a turn of duty throughout the night. Often the train stopped in a forest before a railway station and gave way to military transport." Bojcy" opened the door, and we went out from the carriages to relieve ourselves and to collect branches for the stove. At larger railway stations we got 1 loaf of bread per 4 persons and hot water(" kipiatok") for tea. Every one of us had a little food and was very economical with it. Families took care of their children in the first instance. Sometimes during a stop neighbouring people from kolkhozs came with milk and with pork fat. They did not want roubles only something to wear ie. clothes and underwear in return. Whoever had anything extra would exchange it, especially to have food for their children. The stench of the toilet pipe was becoming worse. We tried to relieve ourselves outside of carriages when the train stopped. At this time military trains travelled everywhere. Platforms at railway stations were covered in so much human waste, that you could not take a step without dirtying your boots. The result was visible in the spring after the thawing of snows. My father told me about this after the war.

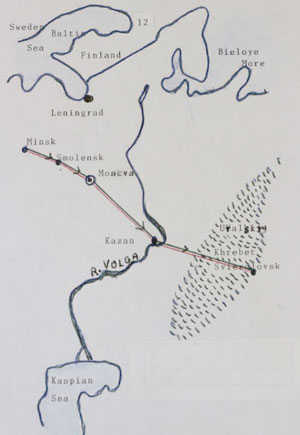

We travelled through Minsk, Smoleńsk, Moscow, Kazan and the Ural Mountains and Świerdłowsk. We entered the region of Siberia, where we were to “live well”. We still did not know where they were taking us. From the first day of our journey illnesses and deaths began, mainly of children and elderly. I will describe the death of one child and of an old man, so that the next generation knows, what communism means.

Roman’s hand-drawn map of their first stage to Siberia

In our train a dozen or so children and elderly died. In our carriage a 4 year old child died. The mother notified a Soviet officer from our train. A soldier came and ordered the parents to throw the child outside into the forest. The father and mother cried and carried out the child and put it in the snow. The father dug out a little snow and tried to dig into the ground. But the ground was as hard as a stone. The child was covered in snow and the parents returned to their carriage. Soldiers closed the doors and the train travelled on.

In one of the carriages was an old man with his family. Mr. Marcin was over 70 and was sent to Siberia in 1910 by the Czar's authorities for fighting for the freedom of Poland. During the Bolshevik revolution in 1917 he returned to his own country and saw a free Poland. He consoled his family, in order for them not to worry, because he knew the conditions in Siberia and that some how they will cope. One day Mr. Marcin sat leaning against the door and he stayed like that through the night. In the morning he was dead. He had frozen to the door. His funeral was similar to the previous child’s. There were also a couple of childbirths, but as the train travelled further and they ended tragically. The Bolsheviks were not concerned whether somebody was born, or died during the transportation of Poles.

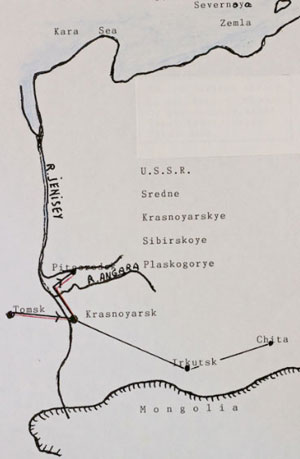

Roman’s hand-drawn map of their journey to Siberia

We travel further along the Trains Siberian railway built before the WW1 in 1914 connecting Moscow with Vladivostok. During the construction of this railway over 20 thousand people died (info from books). We pass Magnitogorsk, Omsk, Tomsk, Novosibirsk and we got to Krasnoyarsk. This is the largest city in central Siberia.

To the gold mine

Before Krasnoyarsk our train entered a side-track, where horse drawn sleighs were waiting.

" Bojcy" jumped out wrapped up in long sheepskins and felt boots (special long boots for walking in snow). They opened the carriages and ordered everyone to go out bringing their belongings. People were divided into several large groups and every group received a dozen or so sleighs. We climbed in with our packages and we moved on. We did not sit for long otherwise we would finish up as Mr. Marcin did in the carriage. Usually we walked behind the sleigh, only little children wrapped up in blankets and hay sat on the sleighs. After a couple of hours we crossed one of the three great rivers of Siberia - the Jenisej (over 4000km long). We travelled long her eastern side. At night we stopped in "posiołki" (kolkhozs) where we got some soup and a little bread. Again we crossed a large tributary of the Jenisey – Angara and then further in to the unknown. There were forests and very deep snow all the way. We passed village houses, which we could not see. They were covered in snow and we only recognised that it was a house by the mound of snow. We were surprised at how the horses went forward without seeing the road. The "Bojec" sat or walked, and had reins attached to sleigh. It was the same at the edge of the forest. After completing work the horses went straight to our camp. After 10 days we arrived at a large village – Pitgorodog, which was over a river inflow Jenisey. Pitgorodog was on the eastern side of the Jenisey about 50 km away.

For my children and grandchildren's orientation here are some details as to where your grandfather lived in Siberia. Brześć n / Bugiem in Poland and Pitgorodog in Siberia are about 400 km apart. From Krasnoyarask to the seas in the north ( Karskoje sea) about 2,000 km. From Krasnoyarska the Trans-Siberian railway travels about 5,000 km passing through Irkutsk, Chita, Khabarowsk until Vladiwostok (Japanese Sea). From the Trans Siberian railway there were no other railway connections to the north. Transportation at this time was dependent on: human legs, carts and sledge with horses and huge rivers. The greatest Siberian rivers are: Ob – Jenisey – Lena, about lengths 4-5,000 Km.

Roman’s hand-drawn map of their second stage of his journey

In Pitgorodku we had wooden houses. Every house had six separate rooms. One room per family irrespective of the number of persons. Inside there were lower and upper bunks for sleeping, and on them hay. In the centre stood an iron stove. On a table stood several dirty pots. My brother and I were allocated to a young childless couple, also from Białowieża. From the first day we repaired windows and doors, in order not to freeze at night. The bunks were infested with bed bugs. There were no toilets in the premises.

My brother was assigned to work in a gold mine about 1, 5 km away. Later we found out, that in this region of Siberia there were more gold mines. I was assigned to fell trees in the forest together with young boys and women. The gold mines were very primitive. A lift took people underground where they sieved sand with water from flowing streams. After finishing work, any ore found had to be given to the foreman in a pouch. The workers were taken to work and back to the camp by armed " bojcy". The return to camp was worst. Trousers and boots were always wet from the mine and whilst walking back 1, 5 km to the camp everything froze. We wrote letter to our parents, asking them to send us large, long rubber boots and pork fat. After two months we received boots and fat, which saved our lives.

My group worked in the forest cutting down large trees for construction (15-20m lengths) and trees for fuel. Trees were cut using handsaws and axes. Branches were cut off and horses dragged then to storage areas. Trees for fuel were cut to 1. 5 m lengths and they were stored 4-6 m high. All workers in the mine and in the forest were paid a couple of roubles daily. Deductions were made for bread, oil and anything they gave us." Bojcy" lived in little wooden houses with one room. By the wall they had a huge oven in which they baked bread. At the front of the oven they cooked their food. Their stove also served for sleeping on. They covered the top in animal skins and it was always warm.

The guards and administration of the camp was largely made up of long standing prisoners, who after 15-20 years agreed to remain in the camp, because they saw no future for themselves if they returned to their former towns. They were people without hearts to whom people meant nothing. They could hunt wild boar, goat, roe deer and nobody would control them. There was no electricity or radio's anywhere. We did not know what was happening in the outside world. We were hungry and we only thought of ways to get something to eat and to protect ourselves from the frost. At the beginning of May the snows began to melt and we could feel spring in the air. Spring arrived quickly and the forests and grass turned green everywhere. At last we could wash our underwear and hang it to dry outdoors. We built a toilet adjacent our home. My brother drank a teaspoon of fat every day and felt better (previously he coughed up blood). I, thank God, had been well up to now.

Fish hooks

When the rivers defrosted I noticed that the river running close by Pitgorodka possesed an abundance of fish. Because in Poland I caught fish from a young age, I immediately thought of how to get hooks to make a fishing rod. I asked the „bojcy" where and how could I get hooks, but everyone said, that non were available because fish are caught using nets in this area. I assured my friends in adversity, that if I had hooks then we would have fish every day. The wife of a professor came to me and said: Roman, have my ring and give it to the " bojec", he will surly find some hooks. I met the " bojcec" and indeed after several days I got hooks. I made the fishing line by twisting the hair's from a horse's tail. First I bound hairs in 6 - 8 metre lengths, and then three such lengths in one thin line and this was very strong. I made a fishing rod from a long thin stick, I found a cork from a bottle and I then had the equipment to catch fish. I found worms in the vicinity of the stable amongst the horse manure. After work and even in the evenings I caught fish. In Poland I caught fish on very nice rivers such as: Prypeć, Pina, Bug, Jeśiołda and Muchawiec. But I had never seen a river so abundant in fish as the inflow of the Jeniseya. I carried fish in buckets all summer long. We had fish soup almost every day, and we baked fish over the fire. The camp commander and his “bojcowie” ruled our camp. We were not allowed to leave the camp without permission not even to catch fish.

After war I was asked why we did not try to escape from Siberia. I answered: the distance, climate, lack of communication, and most of all the orders of Bolsheviks which were well-known to all people living in Siberia. Putting up or helping escapees carried a 25 year sentence of hard labour. Apart from that, people in the camps were largely families, which only death could separate.

The greatest exchange value in our camp was for our watches, rings, cigarette lighters, clothes and mainly ladies underwear. We exchanged these things for food, which was of poor quality. Some people had items to exchange and others had very little. Everyone kept something valuable for an emergency.

People were ill and died from hunger, poor hygiene, and from the lack of medicines and medical help. Very frequently there were fatalities in the gold mine and in the forest. People in camp did not know how to work in these areas and did not know how to use manual lifts, saws and axes. You could not get such things as needles, thread, soap, salt, sugar and fat. Neighbouring Russians wore similar wadded short overcoats and trousers, and in winter felt boots. Our clothes were very inadequate to deal with the Siberian winter. During summer we tried, at all cost to get wadded short overcoats, trousers and felt boots, to survive the next winter. From the end of May to mid October summer and autumn passed quickly. Further north from Pidgorodka the summer and daytime was shorter, and winter and nights longer.

Close by the village was the cemetery, which constantly increased in size during of our stay. Graves – were a mound of earth overgrown with grass and a wooden cross or stone.

All summer we spent preparing for the coming of winter. The first winter of 1940 was short, from the end of March to the end of May.

The next winter - 1940 / 41

The next winter lasted from the end of October 1940 to May 1941, about 7 months. This worried us because we did not know whether we would survive. We built a large toilet adjacent to our house from timber and branches. During the preceding winter we had problems, especially with children at night. In spite of the terrible suffering, everyone wanted to live and never lost hope that one day they may escape from this hell. My brother and I were lonely in this camp. All other people were in families - father, mother, children, grandfather and grandmother. However we were in a family of our own countrymen. We helped each other mutually as best we could.

In October the ground frosts were beginning again and shortly it would be winter. From November we have a real snowy winter. My brother and I feel better thanks to receiving rubber boots and fats from our parents in Poland. We also managed to get padded overcoats, trousers and felt boots. Our camp was mainly populated by people from the Białowieża Forest area eg. professors from the school of forestry, foresters, gamekeepers, workers, management of State forests and others. Several kilometres away was a second camp in which were our countrymen from the Lvov region. They worked as we did, in the gold mines and forests. These were forests like nowhere else in Europe. Thanks to these forests, the winter in Siberia is quite different and one has the impression that it is not so bad. There are no winds but frosts still reach between -30 and -40 oC in winter. We easily contracted frostbite of the feet, hands, nose, ears and face. If one was quick then it helped to rub the affected part with snow and after coming home rub the area with oil and hold it near an open fire. Ordinary people, who knew how to live in difficult conditions managed better in Siberia than the professors and those who were better off. Before winter we again received fats from our parents.

Every winter day, up to mid May 1941 was similar. Frosts, snows, constant hunger and thoughts about what to eat. There was no question about fish because the river froze and there was no point to make openings in ice as in the rest of Europe. Our efforts to get food did not go beyond bread, flour, potatoes, cereals and salt. There were no vegetables and we never saw fruit. In Russia you could only buy what was grown locally. We confirmed this during our journey between 1940-42.

The winter of 1940/41 was the same as the preceding year. Many died in our camp and in the surrounding area. There were no boards for coffins. A deceased person was dressed in his clothes, wrapped in a blanket and placed in a grave. We said prayers and erected wooden crosses with a name and date of birth." The Bojcy" laughed, that Poles go to all this trouble when somebody dies.

From the end of May the snows thawed rapidly and spring arrived quickly. I began to prepare my fishing equipment, which had been so efficient the previous year. After the ice flowed down river I started catching fish. It became warmer and we could bathe in river and repair our clothing. In the meantime something unexpected happened in our camp.

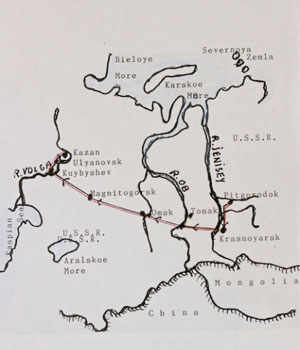

Lenin’s hometown

At the end of June 1941 several members of the N.K.V.D came to Pitgorodka . They went from barrack (house) to barrack and chose young and still healthy people. I was selected. They ordered us to take our belongings and to be ready to leave the next day. Nobody knew where we were going. I bid good-bye to my brother and the next day I set off with my friends in carts. We were surprised that the " bojcy" drove the horses hard and after several days we were already in Krasnoyarsk. The railway station was very busy and full of soldiers. We joined another group of young people; they were Latvians and Estonians. Shortly we found out that from 22 June Russia and Germany were at war. Less than 2 years ago they were allies and divided Poland. The Estonian told us, that the Germans are already outside Minsk and stopping only to fill up with fuel. Our large group was loaded into a train and we set off towards Moscow.

There were many bad and good theories as to what the Bolsheviks intend to do with us. Everywhere there were soldiers and civilians going to join the red army. We were given coffee, soup and a piece of bread every day. This is how we got to Kuybyshewa by the river Wolga. Next day we were taken to the port and we set off by ship to the city of Ulyanovsk. It is the city of Lenin’s family (Illich Ulyanow), it is the military centre for the region and has a plane factory. Our entire group was taken by cars to the outskirts of the city and unloaded in to a camp, where there were summerhouses surrounded by barbed wire. The next day after drinking coffee and eating a piece of bread, we were placed in threes and an officer made a speech " There is currently a war, you are workers and you may not leave the camp. We go to work in the forest and after work we all return to the camp. If someone escapes during the state of war, they will receive 25 years in prison, or even the death penalty". We understood and we were off to the forest about 8-10 km away. A car followed us with saws, axes and other tools. The officer divided us into groups of 12-14 people and ordered us to fell large pine trees, which were marked with an axe cut.

And so now we understood, that we are qualified workers from Pitgorod for tree felling. After felling trees and removing branches it was necessary to report, that the tree was ready. When everybody reported they were ready, then every group (12-14 people) took their tree on their shoulders and carried it to the suburbs of Ulyanovsk. By the evening we were there and we lay the trees in marked places by large holes. We understood our work. We were building so called “ziemlanki” (underground shelters) for the army. After returning to the camp we got soup and cereal. We went to sleep wondering how long we will survive carrying 14-18m trees on our shoulders. We were very tired and as always hungry. We wished the Germans all the best in defeating the damned Bolsheviks. And then we wished that the Americans, English and allies defeated the Germans. And we that survive would return to our motherland.

Sometimes when we passed through the village carrying timber, women came out and gave us bottles of milk or loaves of bread. One day two of my colleagues and I received permission to go to town and to buy something to eat. But we found nothing but a jar of green peas and bottle of vodka. We received some information about what was happening on the war front. In the window of the officer's mess was a map on which were marked Russian and German positions. The Germans were at Smoleńsk and to the south of Kiev. Loud speakers proclaimed that the German has sustained great losses. The Soviet Armies are retreating to appointed places in accordance with their plan.

In Soviet Russia before and during the war there were no radios only loudspeakers. The broadcasting station transmitted programmes to cities where relay stations were connected to loudspeakers similar to telephones. The receiver could only be regulated by volume. Radios appeared in Russia after war, when soldiers began to return with furniture to their own homes. When the first radios appeared for sale, you could only buy the outstanding "stachanowiec" after a wait of at least half year.

The trial of the Estonian

One day a young Estonian from Tallin - a law student was missing from camp. After several days we were called together and taken to the school in town. There was a large hall at the front of which stood a stage as in the theatre. The room was full of soldiers and civilians. On the stage a table and behind it several seated officers. On the left a table and behind it an officer. At the right a table behind which sat the Estonian and a Soviet officer. We understood that there would be a trail of the poor escapee (Estonian). The first to speak was the prosecuting officer. So: the Estonian escaped from work during wartime, which is the same as if he escaped during fighting at the front. Together with a second individual they stole a boat on river Volga and sailed to the town of Engels which was the hometown of second man. Engels was the main city in the Nadwołżańskiej area, a German republic. Then a long speech about how lucky people are to live in a communist state and about the kindness of " słoneczka" Stalin. The prosecuting officer is demanding the death penalty for the two criminals. The defending officer gets up and also makes a long speech at the end of which he asks for 25 years imprisonment. Because these two people do not understand how lucky they are to live in a communist system. The man from Engels was permitted to speak. He asks for acquittal and admits that he made a mistake. Then the Estonian got up and we did not believe our ears when he spoke. In short he said : I am an Estonian citizen, by what right did you take me from my country and deported me to Siberia? If I have committed a crime, tell me which one. You do not have the right to judge me. Many very smart words and our hearts grew because this man had such courage. There was an interval as in theatre and after a moment the officers returned to their places. One of them got up and read the verdict. Taking into consideration their young age and their ignorance, they have been sentenced to 25 years in prison. We returned after this theatrical performance very sad and full of admiration for the Estonian. After the war we found out that in 1942 / 3, when the Germans were near Moscow, the Bolsheviks deported the whole population from the German Republic of Engels, Tartars from the Republic of Tartar (Kazan) and Kałmyków from the southern region of Stalingrad to Siberia.

The Tartar Republic

In August 1941 our group of Poles were loaded onto a ship and again we sailed into the unknown. After a few days we are in town of Kazan. A large town and once again large numbers of soldiers and thousands of civilians being drafted into the army. We were taken to an identical camp on the outskirts of the town as in Ulyanovsk. We started the same work felling trees in the forest and carrying them to the suburbs of Kazan where " ziemlanki" were built for the army. In the camp we met many Poles, and I met friends from Brześć n / B. They told their own stories of survival and explained how they found themselves here. Before the beginning of war on 21 June, they were loaded into carriages in Brześć and transported to Siberia. On the second day in the morning at 03. 00 there were shots in town and planes appeared over the railway station (1km from border). The train travelled east towards Kobrynia. German Tanks were present on the streets. Soviet officers try to get into the train. Planes shoot at the train, but this only lasted a few minutes. The whole transport with guards and officers was retreating from the battlefield and after a few weeks arrived in Siberia to the town of Novosybirsk. From here everyone was transported to kolkhozs. The young and healthy were separated and brought to Kazan. We are together and we are felling trees. After work we are allowed to go out to town, but we must be back at camp in the evening where they check our presence. We joke that Stalin must be getting beaten if the regulations are becoming more lax. In the town there were many soldiers and thousands of civilians waiting for uniforms and transport to the front. One day a few of us went to town. Near the army barracks hundreds of people were being taken to the rifle range. At the rifle range hundreds of people were queuing, waiting for a rifle and a few bullets. At last they get a rifle and a few bullets. They lie down, a " bojec" puts the bullet in to the rifle. The civilian shoots at the target disk closing his eyes and moves on. He has completed his training and tomorrow he will leave for the front. On another day we went to the railway station, where they were loading soldiers into carriages for the Germany front. Dressed in military uniforms, some with rifles and others without. The military orchestra was playing. The crowds were made up of wives, mothers and children. We heard crying and screams. Nearby one woman shouted: Wania where are you going, to fight for this bandit Stalin. We hear other anti communist shouts, which were unheard of before the war. We could not believe that nobody approached (NKWD) to arrest these women. Later we were convinced that the Communists knew what they were doing. When the Soviets started attacking the Germans and found themselves on Polish soil (1944) everything returned to normal.

The town was full of drunken soldiers, but nothing was done to them. We found out from people, that military regiments coming from Ulyanovsk and Kazan were defeated and that the wounded were being transported to the southern republics Of Russia. Towards the end of August we were once again loaded onto ships and taken into the unknown.

To Kuybyshev for amnesty

Our officer tells us, that we will have new work. We sleep on the deck of the ship covering ourselves with our overcoats. We lie one next to another to be warmer because the nights are cool. Constantly we are hungry. On ship there are lots of people trying to escape from the regions near the front line. We received salted flat fish from barrels called płastugą. We were approached by a young woman who asked for fish in return for sleeping with us. I preferred to eat fish. I was reminded of what a “bojca" from Pitgorod told me," you will always want to eat, but you will never want sex in this country". After eating this fish, I got stomach pains and everyone was very thirsty. The ship had water from the river, which we were afraid to drink. I never ate that fish again.

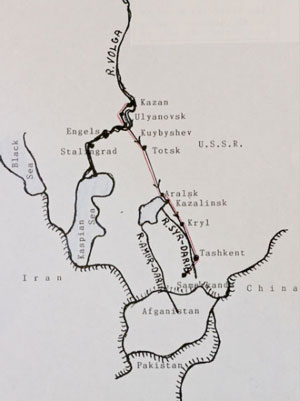

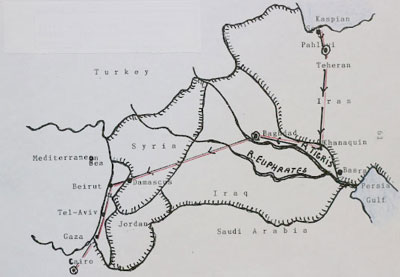

Roman’s hand-drawn map of their stage III and IV of his journey

After a couple of days we are in Kuybyshev. We were put up on the outskirts of the city in barracks such as in Kazan. Apparently these camps must be normal in communist countries. We travelled by car or train to the river port, where we unloaded railway rails from ships. We arranged these rails on a nearby square close by the port. This was very heavy and dangerous work and we were all becoming more physically weak.

After a few days we received good news. The Prime Minister of the Polish government in London and Commander in Chief of the Polish army General Sikorski signed an agreement with Stalin to liberate all Poles from Siberia and from prisons. Joy was in abundance in all the camp. We began to ask our camp commander when we would be free. He answered: slowly, slowly, all will be done formally. Every one of us will receive a certificate but in the meantime it is necessary to work. We found out that in Kuybyshev a Polish agency opened with a couple of officers who are creating a Polish Army. We found this agency and we were told that our army will be in Buzuluk and Totskoje. There are already Poles there who are to form camps for the army. We have to wait for further information. And so we waited and we carried on unloading rails.

One day a ship arrived which began to unload strange soldiers. We did not believe our eyes. They crawled on their knees, dark and had beards. At their sides were armed Soviet soldiers with fixed bayonets. People began to shout "Germany idut" (the Germans are coming). These were Rumanian prisoners of war that were fighting together with the Germans on the Caucasian front. They looked terrible, like walking corpses. One of them could walk no further and fell over. A "Bojec" ran up to him and kicked him and the Romanian fell in to the river. Nobody paid any attention. We were shocked at the inhuman treatment of people, but surprised. At the same time at the railway station a pop (priest) gave his cross to be kissed by soldiers leaving for the front. We could not understand what was currently happening in Russia. People shout at Stalin and communism, the pops walk amongst soldiers with their crosses, officers wear Czar's uniforms. Are we really seeing a change in communism? Day follows day and our situation does not change. Towards the end of August I hurt my leg lowering a rail to the ground. My leg was in blood from the knee down. I turned to my four colleagues from Brześć and said: after work we are going to our camp by train and we will see what is happening at the railway station. If there are trains taking Poles to join the army then we will get on and go. If we come across a patrol of NKWD then you will tell them you are helping me get back to camp, because I have an injured leg and I cannot walk. I tore off a part of my shirt and I bandaged my leg.

After coming to the station we see, that there aren’t many people, instead we hear voices and traffic on the railway tracks. I heard Polish and I said to my colleagues: I am going to see what is happening on the tracks. There was a train with people; I clearly heard the Polish language. I approached and asked: where are you going to my fellow countrymen? To join the Polish army I head. My heart began to pound more quickly; it is now or never. I returned to the station very excited and I spoke to my colleagues about the situation. At the same time a military patrol approached us and asked us what we were doing here. We answered just as we had planned earlier. The patrol left, so I told my colleagues that we should quickly go to the train. My colleagues did not agree and stayed: Roman, you forgot what happened to the Estonian with his comrade in Kazan, for escaping from the camp. The patrol maybe observing us from a hiding place. They are right but my heart tells me otherwise. I answer: return to camp, but I am going with my fellow countrymen to the army. My colleagues left, and I went slowly to the platform entrance. Then as quickly as I could I jumped in to the train with my countrymen. After a couple of very nervous hours waiting the train started to move. I imagined that every step close by the train was a Soviet patrol. During the journey my nerves calmed down, but I was covered in sweat. The further we moved from Kuybyshev the better I felt and I breathed more freely. On the second day we got to the railway station from which the road leads to Totskoje. A Polish officer came out and told us that we can't get out and go to the camp because there is nothing ready in Totskoj. People are waiting for tents, which will be erected for the army. Our whole train is legal and has to go south to the region of Samarkand (Uzbekistan) where a Soviet officer is waiting for us. During the journey we will receive bread, cereals and soup at stations.

The Polish Army in Samarkand

And so again we travel further south and we are even happier because we were heading for warmer places.

At present it is the start of September and soon in the Totskoj region there will be snow and winter. We travel for a week and we are constantly under fed. However we are happier because with every new day it is warmer. The train stopped in Tashkent, where a Soviet officer, the commander of the station informed us, that we were going to Samarkand where we will be looked after. After arriving in Samarkand the Soviet officer said that the Polish army had not formed yet and that he had orders from his authorities, to house everyone in a kolkhoz, where we will wait, until the Polish army begins to form.

We moved off on foot to the kolkhoz about 15 Km away. There were also several women with us who were officer’s wives. After reaching the kolkhoz we were put up in mud huts (houses from clay), without windows and door. We slept on mats on the floor, covering ourselves in our own clothes. Inside was a stove/fireplace made from clay. There was an opening to the roof and one could walk on the roof as on the street. Close by was the river Ladna and you could see fish under its surface. Surrounding the village, as far as the eye could see were cotton plantations. The manager of the kolkhoz, an Uzbek told us, that we will all work picking cotton. If we pick the required amount we will get bread, soup and even meat (mutton).

And so it did not look so bad. We got sacks to collect the cotton and we were told how many pudów (Kg) everyone had to collect to receive some food. The collected cotton had to be taken to the threshing store where it was weighed, noted, and pressed into large bails. And so we went to work in the morning. The plantations had bushes of 1 to 1. 2 m height and at hip height an abundance of cotton tufts, looking like white cotton wool. We worked with many Uzbek women and children (10-13 years old). During the first day we calculated that it would take us 4-5 days to collect the required amount. In course of one days work the women and children achieved a full bag every couple of hours whereas we barely achieved one sack each during one day’s work. We watched how the women and children picked the cotton and we did not believe our eyes. Their hands picked the cotton so quickly it was like a machine, without looking at the bush. Everyone smiled when they watched us work. But they had been doing this from childhood. The result of our meagre production was such that they gave us one agreed amount of food for 3-4 people. And so again we were constantly hungry. We explained, we asked for understanding, but this was to no avail. The Uzbeks behaved kindly, but they had to comply with rules, which were practised a long time. They themselves lived in XVI century conditions.

We heard how mothers rebuked their children shouting, " Budienny will come". It appeared that Budienny was a famous Bolszewik marshal of the cavalry, who after the 1917 revolution pacified the southern republics destroying the mud huts and killing people using his cavalry. The word “Budienny" was very effective. Very few Uzbeks know and use the Russian language. Only those in better positions in work.

I was always thinking how to get a little more food. Apparently hunger is the best teacher. Once again the nearby river came to the rescue. But how was it possible that in all of bolszewik Russia, one could buy a horse, but not a needle or thread and in this instance not even a fishhook. I got safety pins from our women and I shaped them over a candle into a kind of hook. I got some thin strong bits of string, which I rubbed with wax to waterproof them. There was trouble with worms, because the earth was dry and hard. Again I found worms in cattle manure. I began to catch fish, but they constantly escaped because the safety pins did not have barbs. After several experiments I found a way. As soon as a fish took the bait I pulled it out onto the bank. In most cases this succeeded and again we had fish soups. Hunger decreased. We arranged with the foreman, that whilst everyone went to work, I caught fish. Again there was a lack of salt but when hungry everything is edible.

A very interested thing regarding burning fires in the stove. We saw no coal or trees anywhere, and yet the Uzbeks burnt and baked bread. We asked: what do you burn? This is not a problem, come with us and we will show you our fuel. At their mud huts stood piles of fuel. Round, dry and hard pats. Then they showed us, that these pats were to be found on the ground in pastures where cattle graze. These are animal droppings, which quickly dry and are collected for burning in the stoves in the kolkhozs. And so once again we learnt something new in our life.

This is how almost the whole of September passed and our situation was beginning to make me nervous. One evening I told my colleagues: we cannot carry on living like this. Perhaps they are already doing something with our army in Samarkand and all we are doing is collecting cotton and cattle droppings to burn. If we go to Samarkand then we will be nearer realities.

Return journey to Totskoj

Eight colleagues agreed with me and we went to Samarkand. Our women wept, but understood us. The city looked like a huge market place filled with people. The railway station was full of trains with soldiers going to the front and of people fleeing from the front lines in the southern Caucasus. The military rule the station and the entire city. Our entire group kept together. We slept wherever there was room, in parks or in carriages. There were many Poles here in the same predicament as us. But the most important thing was to receive food. In restaurants one could get soup and 200g of bread. At night we stood in queues for bread. During the day we sold this bread to refugees in the trains for higher prices. In this manner we had roubles for soup and bread in the restaurants. And this is how we lived all this period in Samarkand. We always went around together, because gangs from Kiyeva Kharkova and other of large cities prowled in the town and at the railway station. Often we went in to carriages to sleep. Sometimes the train started and we were taken up to 100 km away. We returned. The trains were always full people and amongst them thieves and bandits. I saw a dead man who had been killed with a knife, lying in the corridor of a carriage. On another occasion an Uzbek was sat in a carriage holding a bag with currants. A couple of young thugs stole the bag and escaped. Nobody interfered because they were afraid of being stabbed by the bandits. At night we went to sleep and in the morning I woke up, looked at my chest and I saw that someone had cut away my pocket, which had money in it. Thankfully because we went everywhere in a group we were not attacked. At times passing gangs greeted us "eto swojaki" (“these are our own types”).

So this is how waiting for the Polish army looked. The militia also went around in groups and kept an eye on the order in the bread queues. There was no visible authority in the town. The Uzbeks sat in cafés, smoking long pipes, which were joined to pots of water. We found out from refugees from the Caucases, that the Germans are already near Stalingrad. We still knew nothing about what was happening with the Polish army and it was already October. The days are still warm but the nights cool. At the railway station there was a Polish office manned by a couple of officers. They also knew very little and they gave their opinion that it will be better, only they did not know when and where. We knew that around Samarkand and Tashkent there were thousands of Poles from the kolkhozs waiting for their own army. At last in the latter part of October a joyful message. At the railway station a Polish officer will be recruiting people to form a battalion called " Children of Lvov". Only young people born in the region of Lwow could apply. I had a brother Bolesława who was a policeman in Lvov before the war. I visited him a few times so I knew the street and number of the house in which he lived. Without thinking I turned into a Lwowian, as did my colleagues. The officer recorded our details and said that in a few days there will be a designated number of people who will set off to Totskoj, where the 6th Lwowska division was being formed. We were advised to dress warmly because the winter had started and there were already snows. And so we will go back to Kuybyszew.

Indeed, in the beginning of November we were loaded into carriages (about 300 people in each) and we travelled to Totskoj. After a few days, which were becoming colder, we reached our destination. Snow and winter surrounded us. We had to wrap our rubber boots in rags and we walked quickly so as not to freeze. After arriving at the camp we saw an abundance of tents, and in them straw on the ground. On the next day we had to apply to be verified and to confirm that we were from Lwow. We forgot, that southern Poland, and specially the region of Lwow had a special dialect, and that we have a different one. We were asked different questions relating to Lvov and the region. Finally we were told: you can lie but not to us, you can not be accepted into the to battalion. We were directed to the 17th infantry regiment instead. We were satisfied, that at last we were in the Polish army. I met my professor from the economics school in Brześæ who was a lieutenant and he took me in to his own company. 12 people were allocated to every tent. We made ourselves a sleeping area using timber and branches about 70cm above the ground. We got sacks, which we stuffed with straw, and we put them on the sleeping area. At the entrance we had a low stove made from bricks and clay, with a metal sheet on top and a pipe going to the outside of the tent. We covered the tent with snow so that we were warmer. We slept with 6 people on each side of the tent. We collected branches and fuel in the forest, which we arranged near the tent. Every night one of us took turn guarding the stove. At night we had to be careful to ensure that our heads did not touch the tent, because our hair could freeze to the tent canvas. That is why we slept with a head covering. In the morning we got coffee and bread, at dinner we had soup and in the evening coffee and bread. I received some long boots and I was very satisfied. But I always had to walk around with a little pail for food and for branches. Our army grew every day and that is why there was never enough food. From the soldiers who were here before the snow settled we found out, that around Totskoj lie fields of potatoes and cereals, which have not been dug up. The men had been drafted into the army, and the kolkhoz members were not allowed to harvest food for themselves. All the time we asked ourselves: who will survive the winter here from our group?

We got up in the mornings, did a little exercise and a run, and during the day we listened of talks given by officers on various themes. We were also very busy searching our clothes for lice and then throwing them into the fire. Nearby Totsk (30 km) was Buzuluk, the base of the II Corps with gen. Anders in charge. In mid November there was great news for all Poles in Totsk. The Commander in Chief and Prime Minister of the Polish Government in London gen. Sikorski is coming to Totska, to see his army. Everyone who could walk went and stood in ranks so as to file past their Commander. I will remember this march past to the end of my life. Gen. Sikorski stood at the kolkhoz building surrounded by Polish officers and a few Soviet officers. We all marched past looking like beggars: without boots, rags wrapped around our legs, in torn overcoats tied up with bits of string. However we had smiles on our faces and gazing at our Commander. After the march past an officer told us, that gen. Sikorski wept watching his future army. In December there were rumours that after Christmas everybody from Totska and Buzuluk would be transferred to the Smarkand region. This is what Gen. Sikorski agreed with Stalin during his November stay in Russia and in Totsku. The English were already transporting uniforms and food there. We all began dreaming about food. We hoped to hold out until this trip.

All college graduates, myself included, were signed up to the officer's school, which was to be in neighbourhood of Samarkand. Every day before Christmas, we dried a piece of bread on the stove, which we saved so as to eat a little better on Christmas Eve. A couple of days before Christmas a colleague informed us, that a kolkhoz member came by sledge and is selling hog's meat (rąbanka) at a very high price, but he prefers to trade for clothes or underwear. I had a jersey under my bedding because it was infested with lice. I kept it for a long time in the snow, but the lice did not escape, because they preferred the warmth. I was afraid to trade using this jersey. A colleague gave me advice: Roman, put this jersey on, ask the kolkhoz member if he will accept it. If he agrees, take off the jersey, take the meat and run to your tent. This is what I did and we had splendid Christmas Eve.

Morally I did not feel too good, but hunger was stronger. After Christmas we received more news. At the station in Totskoj there are already carriages and we are being loaded for a journey to a warmer area.

In January we are already in Uzbekistan and we are near Samarkand. This was my third journey between Totskoj and Samarkand. Our regiment and the 5th division settled in the locality of Jacobak. We were happy because it was warm during the day. All the graduates were called together and after a couple of days we were in the officer's school in Szachrizjab. Here I met another one of my professor's (of history), who also became a pupil of the officer's school. This was the first military college in Russia after the amnesty. We received English uniforms and blankets. But first of all we had to go to the baths in Szachrizjab. In

“banii" baths we took off our rags which were burnt. Then women cut all our hair and then we went to the baths. I must describe the baths because certainly nobody from Europe has seen or read about such baths. Huge rooms full of large casks of water. In the centre of the room several large stoves with openings. In the stoves are large fires in which lie large stones. When the stones became heated, we picked them up with special handles and we threw them into the casks with water. In this manner the water was heated. Using a 2-litre dish we took water from the cask and poured it over ourselves, using something similar to soap. This was our first bath in Russia and we were very satisfied. We were also proud that perhaps the famous Tamerlan from Samarkand, who had a palace in Szachrizjab, built these baths. The ruins of this palace were close to our camp. Tamerlan from Samarkand reigned in central Azjii between 1369 - 1405.

After leaving the baths we received new uniforms and English underwear. We felt new-born. The commander of the school was gen. Tokarzewski, who was the commander of military district of Lvov. The educational officer was the famous Polish poet Lieutenant Broniewski. Other well-known persons from Poland who were now being trained were prince Zamoyski and Radziwiłł, Krupa the musician from Lvov, the lawyer Żomnicki and many others. Our tents stood not far from a river in a very nice region.

We began daily exercises in the field and had theory indoors. Food was a little better than before. We also got one pack of tobacco "kuraszki" per week and with the help of newspaper we made cigarettes. This was tobacco from the roots of the tobacco plants. I was lucky that I never smoked cigarettes. My professor chain smoked and he exchanged his bread portion for these "kuraszki". I gave him my pack, so that he did not have to give away his bread. The professor was very weak physically and had no wishes to become an officer. At the start of March he set off to Iran together with orphans, where he was to organise schools.

Spring started and it was very hot. Round our camp were several irrigation channels in which one could bathe. Many of us became ill because there was a large change in temperature and little nutrition in the food. We played football a few times with the Uzbeks. We heard shouts of "bravo englezi". After the game we asked why they shouted "bravo englezi". They answered: because "politrucy" told us, that you are Englishmen and you came to help Russia fight the Germans.

Our period of training passed quickly, the exams started and then the ranks were awarded. I received the rank of corporal (cadet officer). At the end of June 1942 we returned to our own regiments in Jacobak.

Cemeteries in the desert

Jacobak changed beyond recognition and looked tragic. In every tent there were 11 soldiers. Around the kolkhozs and close by the railway station there were thousands of people - Polish mothers, wives and children. There were graves around the camps, everywhere one looked, with crosses made from sticks. When going to the kitchen, women and children stood everywhere in such a poor physical state, that one could not look at them indifferently. Crying children with shining eyes asking for food. We gave what we could. The result was that we were all hungry. The Russians only gave food for the soldiers. And here were at least 30% more civilians. The heat was unbearable and mortality high.

There were rumours that the Russians want to send us to the front line to fight the Germans. Gen. Anders does not agree, because we can hardly stand and we have not seen a rifle yet. Our camp is about 100km from the border with Afghanistan (Pamir Mountain). There was a plan - if the Soviets were to force us to go to the front, then we would march to border, because the Uzbeck population is with us in heart, and there is no Soviet army in this region.

Mortality is constantly growing in the tents and amongst the civilian population. In my tent two colleagues have already died. The diseases that are killing us are: typhoid, malaria, jaundice, scurvy, dysentery. In the vicinity of our tents were open holes. We all went to these holes for our needs. The very ill often fell in to these holes and did not return to their tents. I too felt worse. My teeth became loose (scurvy) and I had yellow eyes. Orphaned children were being transported to Pahlewi in Iran from the end of March. Physically and morally, we were completely exhausted. This is how weeks passed with no hope. At last at the beginning of August we had great news: gen. Sikorski agreed with Stalin, that the whole army under the command of gen. Anders will leave to Iran and will join the 8th English army. Before departing to Iran, whilst going to the kitchen I met two civilians, my colleagues from work in Kuybyshew. They had intended to escape with me to the army, but returned to the camp from the station. They did not believe that I was Roman. They were very weak and could hardly stand. They were released from work to join the army two months ago. Why were you held so long? They said: Roman, a week after your escape, they assembled us all and read us the sentence which you were given. And namely: Roman Olczyk was caught and was convicted for escape from work during war and sentenced to death - a sentence that was carried out. None of us tried to escape. They hardly made it to our camp. They told me about their experiences during the two months. Firstly about hunger, they even ate dogs. Death accompanies adversity. But at last they got to the Polish army.

Before the trip, doctors began to go around the tents to determine who was still healthy and could get to the train themselves and survive a couple of days train journey and two days sailing from Krasnowodzk to Pahlewi (Iran). I got huge shock: Roman you have acute jaundice, dysentery and your teeth are very loose (scurvy). You can not go, you must remain, and you will be taken to a hospital. These are the instructions of a Soviet officer, who was present in every regiment. I saw these officers in czar's uniforms, and amongst them pops with crosses. I began to plead with the doctor, to give me a chance to escape from this damned country. If I remain, I will commit suicide. I spoke seriously and with real determination. I will manage to reach the train and to get to Pahlewi. I prefer to die en route amongst my own countrymen than to remain here with the Bolsheviks. In the end the doctor agreed, entered my name on the list and I felt better. At the railway station we had large stores with English uniforms and with tinned food. The Soviets forbade us to take these into the carriages and to take them to Iran. Our officers allowed every soldier to fill their knapsacks with as much as possible and namely: shirts, boots, trousers, tinned foods etc.

The last few days before the trip were very nervous. In my tent only 5 remained out of eleven a few months before. The surrounding graves were levelled with the ground by winds; crosses lay on the ground. In fact there was no sign that our fellow countrymen lie here, and certainly there will be no trace in the future.

The journey to Krasnowodzk

Stage VI and VII

We started loading ourselves into the carriages and wagons of a train at the railway station. Everyone looked at the distant cemeteries and wiped their eyes. Our train started and after a moment stopped. We hear shouts and crying. What has happened? In front of the train, on the tracks, as far as the eye can see, lie: mothers, wives and children, and so the train can not move. Take us or travel over our bodies. We took everybody in to the carriages and we moved on. We stopped like this a couple of times. As a result almost everyone stood in the carriages, and the healthy got on to the roofs of the carriages.

It was humid in the carriages and there was a lack of water to drink. Everyone was asking whether we would get to Krasnowodzk? I am in a passenger wagon, which is also over crowded and I feel very weak. At every stop I left the carriage, to relieve myself (dysentery). The train stopped in Bukhara and again I went out. I sat under the carriage when a Russian railwayman stopped near me. What are you doing under the carriage? I answer that I have dysentery and other diseases. Do you have English tinned food? Yes I have it in the carriage I answer. Give me this tinned food, and I will give to you bottle of vodka. Drink as much vodka as you can and lie down on the upper shelf. There are only two possibilities, you will recover or you will die. I gave him this tinned food, I drank as much vodka as I could and I lay down on the upper shelf. I told my colleagues what I had done and I asked, that if I die, they should remove the dog tags from my neck and some time after the war inform my parents. I lay on shelf for almost two days and I did not move. In Krasnowodzk everyone began to get out of the carriages. My colleague moved me, and I got up and they were glad, because they thought, that I was dead.

On the second day we boarded a goods ship “Żdanow". Soldiers and civilians occupied places on the deck and wherever else there was room. The ship set sail. People begin to shout anti bolszewik slogans. Officers ask for calm. The Soviets can turn back the ship, because we are still under their authority. Everybody quieted down and occupied their places. On board the ship it was so crowded that one could not move. The very ill occupied places at the ship's side, because getting to a toilet was out of the question. We quickly made curtains from sacks to tie to the iron handrails of the ship's side. People relieved themselves directly into the sea whilst holding onto the handrail. Every so often somebody died and a priest prayed as the corpse slid down a board into the sea. During the 2 days travel from Krasnowodzk to Pahlewi very strange things happened. Anyone who wanted to get to the ship's sides, had to make there way through the mass of people lying on board. When they returned, somebody else would have taken their place. People who experienced it can only understand this. I occupied a place in a large ventilation funnel near the ship's sides. After 2 days we were in the port of Pahlewi. People in the vicinity of the ship walked with handkerchiefs against their noses. Our ship was something unimaginable. A swimming sewer. A fire engine arrived and began hosing the ship down. We began to disembark from the ship and behind us were the sick on stretchers some of which were hardly alive.

On the beach in Pahlewi

We walk through the town and we do not believe our eyes. Shops, bread, fruit, smiling people greet us. I nearly smashed my head on a lantern looking at all this.

Several kilometres from Pahlewi we were taken to the Caspian Sea, where there were tents and hospitals waiting for us. The healthy were directed to tents, and the ill to hospitals. We were assigned quarters with our regiments in vicinity of the beach. We all began a march to the kitchen for food. We were told not to eat too much, because there was plenty of food. Having weak stomachs, an excess of fatty food, could do us harm. But not everybody listened to the warnings and the hospitals filled up with ill people. According to later information after leaving Krasnowodzk approximately 4 thousand people died. I decided not to eat too much, only enough to combat my hunger. I ate little but often. After several days my stomach began to function better and I felt well. In the vicinity of our tents the Persians laid out their tables and sold food, fruits and trinkets that were required by us.

Soldiers received their first soldier's pay according to their rank together with cigarettes and chocolate. There were basins with fresh water and decent toilets built. We received new uniforms and underwear. Every other day there was time for a bath in the sea, food and ball games on the beach. We slowly began to gain weight and our mental state was returning to normal.

This lasted about 4 weeks and then the army began transporting soldiers to Iraq. We were transported by cars to Teheran, through high mountains with very winding and dangerous roads. Our excellent chauffeurs were Persians and Englishmen who knew the mountainous roads very well. At the start of October 1942 we crossed the border in to Iraq and we stopped a plain in the vicinity of a river.

Meeting with my brother in Iraq

The 2nd Corps camp occupied a huge area close by a refinery and Khanaquinie and Quizil-Rabat. One day, as I was leading my platoon to the kitchen I saw my brother Czesław walking opposite. Joyful crying and an exchange of stories lasted two days and nights. He met a soldier from my regiment, who told him that I was in the vicinity. My brother was released at the end of May 1942 and hardly had time to join our army in Samarkand, before our departure to Krasnowodzk. His journey to the Polish Army was similar to everybody else’s. Hunger, diseases and the death of colleagues was the normal picture. The release of Poles from the Siberian labour camps depended on the political party and authorities in each area. They governed how they wished. Siberia is a huge country and never has inspections. Many Poles were not released from the labour camps until after the war in 1945/6.

Iraq 1942

A new reorganisation of the army began. We got armaments for training. Driving lessons began. In November 1942 again we had joyful news: Gen. Sikorski is coming to review his army. Everybody in uniform and nourished, we marched with rifles before Gen.Sikorski and English officers. Orchestras played marches and we passed smiling as never before. I marched in the guard of honour formed from Officer Cadets from the 5th and 6th division. Currently we have constant exercises with the weapons we will take to the front to fight the Germans. The commissioned and non commissioned officers training schools were operational.

We played football for the championship of the 2nd Corps. I spent Christmas together with my brother by a Christmas tree made from palms in Quizil-Rabat. In January and February the constant rains fill dry streams and riverbeds. Water floods the roads and our camps. By the end of February (1943) the desert changed beyond recognition. Grass begins to grow everywhere, which reaches the height of a man. In the grass, which has thick stems, coloured flowers grow which are similar to poppies. The whole desert looks like a carpet. When after some time we have very hot days, the sun burns the grass completely and the desert looks as it did previously. Droves of sheep wander on the sand and graze on the burnt grass.

Christmas 1942 Quizil-Rabat

Italy 1943

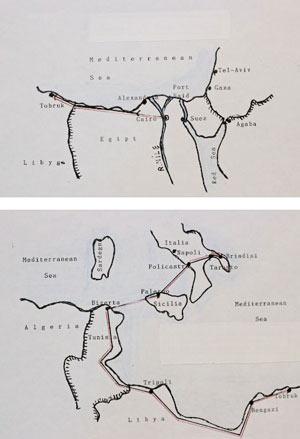

In April we travel to Baghdad and after short stop, further on through Damascus (Syria) and Beirut (Lebanon) to Palestine. In Palestine we are based in Gedera. In June 1943 I was recruited by Col. Święcicki to a special parachute unit and we left to Egypt near Alexandria. Here we were trained by English and Polish officers. Our unit was called “Base No.10". The Commander is Major Kryzar. In November 1943 we are loaded into vehicles and we travel along the North African coast. We pass Tobruk, Benghazi, Tripoli and we are in the port at Bizerte in Tunis. We sail by battleship to Policastro in Italii. In to vehicles and we travel to the port of Brindisi by the Adriatic. Our unit and group of Polish airmen occupy the airfield in Brindisi. We live in Ostuni about 20km distance from the airfield. Col. Święcicki, Col. Okulicki (later a general) and several higher ranking officers are with us. My parachute identification is: Nr4522. Confidential order No 7 dated 21. 03. 1944 L. dz. 244 / tjn / 44. We spent Christmas together at base No 10 by a memorable Christmas tree in Ostuni. The activities of our unit are described in the book entitled “Cichociemni". At the end of January 1944 gen. Anders and the 2nd Corps arrive in Italy.

Roman in II Corps Italy with Parachute Insignia to replace ‘Cichociemni’ insignia.

During the August uprising in Warsaw the English authorities disband our unit in accordance with Stalin’s demands. Those of us remaining become assigned to various units in the 2nd Corps. I became assigned to the 7th Anti Armoured Regiment. During the fighting on the front line I receive an officer's rank of second lieutenant. I possess seven military honours. At the end of the war towards the end of April 1945 I finds myself near Bologna. In 1946 the 2nd Corps is transferred to England.

Northern Italy 1945

At present being 80 years old, I live on the island of Anglesey in the town of Beaumaris, my wife’s hometown. I thought, that my grave would be in my family town of Kalisz called " Polands Venice".

Sad conclusions

Being in the 2nd Corps we were young and every one of us thanked God, gen. Sikorski and gen. Anders for rescuing us from Siberia. We were not interested in politics and we only thought about Poland and her fight with Germany. We conquered Tobruk, and Benghazi in Africa. Monte Cassino in Italy. Flights to Poland from Brindisi. Many crosses and medals on our chests. In the mean time in 1943 Gen. Sikorski died in a plane crash but the pilot survived. For Monte Cassino and other praiseworthy acts the English withdraw their acknowledgement of our government in London. Instead they acknowledged Wanda Wasilewskas communist government in Poland. When a national hero (English) was asked in Parliament why? He answered: " I would even break a contract with the devil to save my motherland”.

After we settlement in England, gen.Anders complained to Churchill about the conditions of existence, and he also got a good answer: "if you do not like it here then you can return to your own country, nobody is keeping you here". Yes, only Stalin and Hitler broke pacts and contracts. One can quote many examples of the way we were treated, even during the fighting on the front line. Was saving us from Siberia, Mr Churchill’s real and honourable intention. If in 1942/3 the Germans conquered Stalingrad, they would have been very close to Baku, Mosul and Kirkuk in Iraq. There were already Poles there. The map of the world would look different today. The Polish Army would be written off in the Siberian wastes and nobody would have heard about a great hero. The main aim was the British Empire, at any cost. This was obvious after the war (and even during it). Defeated Germany was rebuilt but not Poland. Poland is made up of Slavs, who are second class citizens and are treated as such by the West to the present day. Currently Poland should take example from England and her politicians (heroes). We see many films about the Jewish holocaust thanks to directors who are millionaires. Even with anti Polish propaganda. Why are there no films about our army - the 2nd Corps and how this army was formed? If it was not for Wankowiczs book "Monte Cassino", then not a lot would have been known about our battles and about Katyn. Apart from that we do not have millionaire directors and up to 1990 there could be no mention about such films. In English literature there is only mention about the activities of the English and American armies on all fronts of the world. Who fought in these armies, where and how is seldom described.

I spoke with my daughter (50 yrs old) one time :" Father it true and is it possible, that during the last war 6 million Poles were killed ?" I answered:" yes it is definitely the truth and I will add, that 300 thousand British Citizens were killed.

Do you know that:

The number of Poles deported to Siberia were:

|

In February

|

1940

|

220,000 people

|

|

In April

|

1940

|

320,000 people

|

|

In June

|

1940

|

240,000 people

|

|

In June

|

1941

|

265,000 people

|

Prisoners of war, Poles recruited to the Red Army and taken away to labour camps and deep into Russia before June 1941, 647,000 people.

Together 1, 692,000 people

To the end of September 1942, gen. Anders managed to lead out of Russia an army, children and women totalling only 114, 462 persons. Polish orphans transported to Eastern Africa - 16,000 people. The data above is from the book entitled “Scattered around the World".

One of the many Polish diaspora 1946

Stages of my journey

I Breeze n / Buggies – Pitgorodok

Brześć n / Bugiem – Mińsk – Smoleńsk – Moskva – Kazań – Uralsk – Sverdlovsk – Omsk – Tomsk – Krasnoyarsk – Pitgorodok

II Pitgorodek – Kazan

Pitgorodek – Krasnoyark – Omsk – Magnitogorsk – Kuybyshev – Ulyanovsk – Kazań

III Kazań – Kuybyshev

Kazań – Ulyanovsk – Kuybyshev

IV Kuybyshev – Samarkand

Kuybyshev – Totskoje – Orenburg – Aralsk – Aktyubinsk – Kazalinsk – Tashkent – Samarkand

V Samarkand – Totskoje

Samarkand – Tashkent – Kazalinsk – Aktyubinsk – Aralsk – Orenburg – Totskoje

VI Totskoje – Samarkand – Jacobak – Shakhrisjabz

Tokstoje – Orenburg – Aralsk – Aktyubinsk – Karalinsk – Tashkent – Samarkand – Jacobak – Shakhrisyabz

VII Jacobak – Pahlewi

Jacobak – Bukhara – Ashhabad – Krasnovodsk – Pahlewi

VIII Pahlewi – Khanaquin

Pahlewi – Teheran – Khanaquin

IX Khanaquin – Benghazi

Khanaquin – Baghdad – Damascus – Beirut – Tel-Aviv – Cairo – Alexandria – Tobruk – Benghazi

X Benghazi - Brindisi

Benghazi – Tripoli – Bizerte – Palermo – Policastro – Brindisi

To my daughter Maria

Memories of Siberia

1940 / 42

Roman Olczyk

Born 27. 09. 1919 in Kalisz

|