|

Władysław Popiołek

My name is Władysław Popiołek and I was born in Strzemieszyce, near Katowice, in 1923. At the outbreak of World War Two I was living in northern France with my family. I undertook my basic military training and when the Germans crossed into France my father and I and other Polish neighbours tried to reach Dunkirk to help the war effort. There was no organisation locally on the part of the French to resist the invasion. This first attempt was in vain and we had to return home. However, I was determined to fight the Nazis and in August 1941 I left my home in Croix (without my parents knowledge) and started to journey south with a friend, Czesław Maciag, a Polish airman who was trying to rejoin his unit. I was 18 years of age.

France and Spain

Czesław and I managed to travel through the length of France, across the Zone Interdite and the Zone Libre, using various trains, and by walking, to reach the border with Spain. We were hoping to cross into a neutral country and make our way to England. We reconnoitred the border and late one evening we swam across the River Bidassoa in our attempt to reach Spain. Far from being neutral, the Spanish border guards arrested us, threw us in jail, stole our money and two days later the Spanish Police paraded us in the streets in chains like common criminals. They took us to the Campo de Concentration de Mirando de Ebro, near Vittoria. This was a concentration camp built under the supervision of the Germans to house prisoners of General Franco in the Spanish Civil War. The camp has since been demolished.*

*There is an account of life in this camp called the “Urge to Live” by Bolesław Wysocki

Władysław Popiołek bottom left at Miranda de Ebro Concentration Camp September, 1941

We declared ourselves to be Poles, and I was to be kept there without trial for 20 months. I was young and always hungry. Conditions, especially in the beginning, were harsh. However, I was with other Polish prisoners, about 270 to start with and this number gradually grew to 600. The Poles and many of the others in the camp had been captured whilst trying to rejoin the Allied forces. We organised ourselves into a prison community and the acting Polish doctor Leon Slupinski took me under his wing and became the elder brother and friend that I had never had. He had fought at Narvik alongside the French Foreign Legion and was later decorated by the Norwegians and the French for his bravery there.

Meanwhile, in the outside world, the war was continuing and following negotiations between General Franco and the Allies, hope built that we were to be released. As our clothes were in rags, we were given new ones by an American charity, and divided into groups of 100. I finally left the camp and marched through the gate and out of the hated barbed wire confines with 99 other Poles on 21st March 1943.

Released from the concentration camp El Escorial 22 March 1943

We travelled by train to Madrid, and then by bus to Escorial where we stayed for two weeks. We were then sent back to Madrid for a further three weeks to recuperate and again boarded a train, this time to the Portuguese border. We walked across from Spain and were taken by train to a port in the Algarve called Vila Real de Santa Antonio. There we boarded a coastal tramp flying the Belgian flag which liaised just outside the three mile limit with a British Destroyer, The Antelope, which we had to clamber up using nets. Mountainous seas made us all seasick, including the sailors, but we finally approached the calmer waters of Gibraltar.

Gibraltar and travel to the UK

At Gibraltar, we were marched to the ancient fortress halfway up the Rock and assigned a cell – we were not prisoners, the doors were open. We were in the hands of the British, and we were kitted out in khaki as part of the Polish Forces and paraded in front of the then Governor of Gibraltar, General Macfarlane. I was there for about three weeks.

I was one of about 250 Poles who were embarked onto the City of Norwich, an 8000 ton ship converted into a troop carrier. The ship travelled in convoy to the UK and endured bombardments and rough seas; the sheer noise of the anti aircraft guns and bombers was terrifying. The battle weary crew finally docked in Avonmouth, as we were unable to reach Liverpool due to it being heavily bombed at the time. We left the ship in grey weather under the eyes of unfriendly dockers and were put on trains, under some very friendly guards, bound for Scotland. We reached Kinghorn and were once again behind barbed wire in a camp to be processed for two weeks. But I was treated well there and given a bunk and food, and soon we were allowed out of the camp, and sent to the castle in Dunbar to recuperate.

Training

Second left, sitting, Officers Training Corps, Auchtermuchty 1943-early 1944

I started training with the Officers Training Corps in Signals in Auchtermuchty. After passing my exams, I had the chance to volunteer to train for flying with the Polish Air force. I was then billeted in Blackpool.

Training was slow to start. However, eventually I undertook my written exams at RAF Croughton and then began to learn to fly at RAF Hucknall in June 1945 on Tiger Moths - 25 (P) EFTS.

Wladyslaw Popiolek, second in, training on Tiger Moths, RAF Hucknall

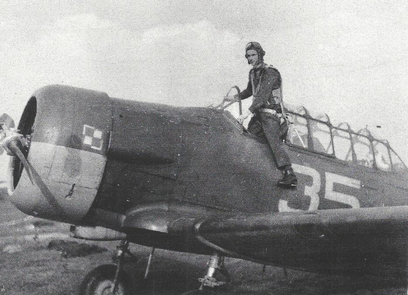

I continued to pass exams and started training on Harvards to become a fighter pilot in the Senior Flying Training School at RAF Newton– 16 (P) SFTS - in September 1945.

Training on Harvards, RAF Newton

Already it seemed that there was uncertainty as to how many new pilots would be needed and once the Yalta Agreement was signed, there was a question mark as to whether Poles would have a place in any further training. The course that I was on, Course 41, was disbanded. Then suddenly a few students, myself included, were selected to start again on Tiger Moths, and then Oxfords at RAF Newton.

But it was not to be. My last written exam, after which I would be a trained pilot, was to be on a Monday, but on the preceding Friday, all training stopped and we were disbanded. We urged our commander, Captain Krasnodedebski to reconsider, but this was a political decision taken by the British government of the time. It felt frustrating and wasteful.

We were given choices, namely – 1) Return to Poland or 2) Join the Polish Resettlement Corps. I also had the choice of returning to France, as I was a naturalised French citizen. I chose to join the Resettlement Corps and was sent to one of the camps, in the picturesque village of Castlecombe. In the winter of 1946-47 we were snowed in there, and it was from here that Poles applied to go to various countries of the world, the USA, Canada, South Africa, and South America. A return to a free Poland, which we had all fought for, was not possible as it was now within the sphere of Stalinism and would be dangerous. In the meantime, whilst I waited to be resettled, I was sent to work on kitchen chores at RAF Watnall, near Nottingham.

Resettlement in the UK

As I had chosen to stay in the UK, I was sent to the Derby Labour Exchange. The British Celanese Company in Spondon, Derbyshire, interviewed me and I was offered the job of fitter’s mate at £5 per week. A boarding house was found for me, I was given a pair of trousers, an Irish tweed jacket and my Air Force overcoat and battledress and kept my shoes and underwear. I also received a Post Office savings book with £16. My civilian career had begun.

The years following the end of the war were hard for everyone in the UK, with the country in debt and with men returning from combat around the world. There was rationing, a housing shortage and an economy to re-build. As a foreigner I realised that I had to work just that bit harder to prove myself, and so I did. Evening studies, long work shifts, an External Degree in Chemistry from London University, night work and more. Gradually, I achieved success working for others and eventually running my own business.

Now I take pleasure in the achievements of my children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and the opening up of Eastern Europe finally allowed Poland to become free again and develop economically. I visit from time to time.

Receiving the Membership of the Poznan Airforce Association, November, 2011

Members of the Poznan Airforce Association.

Władysław Popiołek in the centre, with son Marc to his left

Władysław Popiołek, April 2014

|