Continental Action

Akcja Kontynentalna

Introduction:

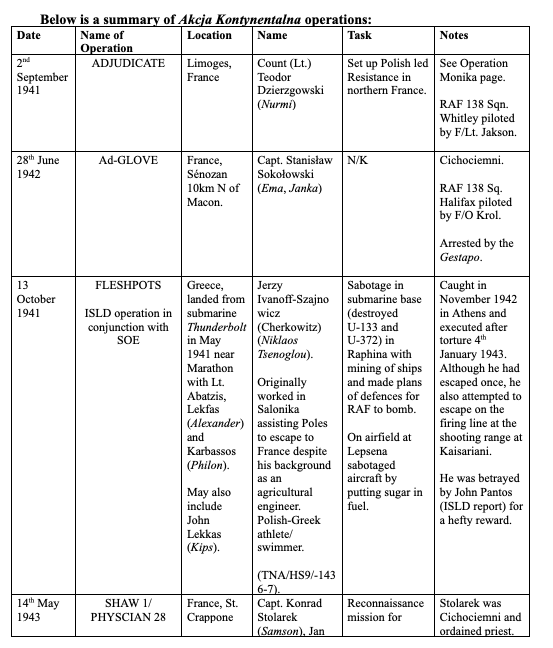

If you go to any book index specialising on Polish history during World War II and look up ‘Continental Action’ (AKCJA KONTYNENTALNA) you will find very little that addresses this topic in any detail. While Krzysztof Tochman has chronicled biographies of many Cichociemni that adds detail to operations, the objectives, remains incomplete. Continental Action was a highly secret underground network for the collection of intelligence by Poland across Europe, Scandinavia, and Latin America whose function included subversion and a quasi-diplomatic service in occupied and neutral countries (TNA/ HS4-315; TNA/ HS4-319). Its role and influence on strategic planning of the war has generally overlooked and not given the profile it deserves and yet gave the Allies a strategic advantage over the Axis in many theatres of the war.

In the autumn of 1940, the significance of a large Polish diaspora in France began resistance to the Nazi regime that needed coordination with military and technical support to become effective (Pepłoński, 2005). Jan Librach, the former secretary to the Polish embassy in Paris was entrusted to develop a new resistance organisation with separate offices and field stations to II and VI Bureau. Overseen by the Ministerial Committee, headed by Professor Kot the operations in France were led by Aleksander Kawałowski (Hubert) who acted as the commander of POWN (Polska Organizacja Walki o Niepodległość). Maj. Jan Żychoń, Chief of the Intelligence Department would act as liaison officer between II Bureau and POWN. It was clear from the outset that the Polish diaspora would provide a global network for Continental Action to conduct anti-German or Axis military and economic intelligence gathering with subversive activities commencing in France and Belgium first (Maresch, 2005; Pepłoński, 2005). Continental Action (sometimes referred to ‘Kot’s Organization in TNA/ HS4-221) was initially controversial amongst Britain’s intelligence community since II Bureau and the AK were already providing an intelligence service. The initial plan was to strike at transport networks on the French-Belgian border, organising a general strike in the coal industry and creating a diversion centre in Caen. Included in the plan was to gather intelligence from the Axis countries and develop economic warfare which required two departments within Continental Action to emerge covering a) military and b) civilian targets (Pepłoński, 2005). The embryonic organization would provide a strategic advantage over the Third Reich (Kajetanowicz, 2017).

Professor Stanisław Kot

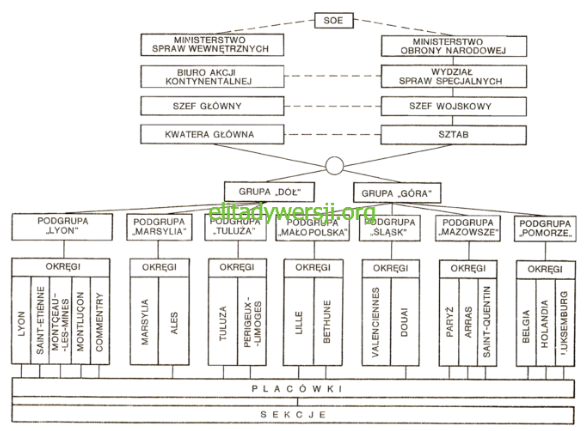

The organigram covers the structure of Continental Action and how regions within France were covered. The operation was fraught with internal politics and meddling by key players with Professor Stanisław Kot taking a leading role (McGilvray, 2010). The politicisation of Continental Action threatened the security and effectiveness of the Cichociemni sent into France and Poland for sabotage, diversionary activities and political subterfuge while also collecting military and economic intelligence. Reorganisation separated military from civil targets, to resolve the disputes between the Ministry of the Interior and Ministry of National Defence (MON). However, this seems not to have lessened Kot’s meddling, intrigue and misinformation given to SOE, especially E/UP section that threatened to blight the operation’s objectives (TNA/ HS7-184).

Source Link

Kot used every opportunity to promote the future of his Peasant’s Party within Poland’s armed forces in the Middle East (McGilvray, 2010) and his politics were detested by Anders who refused to remove Sanacja supporters from the army. While the Polish government-in-exile was a legitimate stakeholder through being a coalition of pre-war parties, the ideological and political differences would test a government of ‘national unity’ particularly after the Sikorski-Majski agreement (Stola, 2012).

While Kot and Retinger who acted as Chargé d’affaires were instrumental in overseeing the Sikorski-Majski pact that had been signed on 30th July 1941 in London, their roles in Moscow were somewhat limited and Sikorski drew criticism for his choice in envoys since Kot may have antagonised Soviet-Polish relations due to his reactionary leaning (Soroka, 1976). The diplomatic breakthrough for Sikorski had been through Stafford Cripps using backchannels for an amnesty and release of Polish POWs (Kochanski, 2012). General Kazimierz Sosnkowski, who was responsible for the military communications must have been relieved when the decision was made to separate military targets from the political and economic ones. Whilst there were concerns by the head of Polish intelligence Stanisław Gano too, the plan to use the Polish diaspora within Continental Action appears not to have undermined or compromised military targets and communications despite their misgivings in the use of the Polish diaspora. Józef Retinger too had a hand in promoting the idea of Continental Action since he had the ‘ear’ of Churchill. Described as éminence grise was also a master of intrigue (Kochanski, 2012). Retinger’s role in Continental Action is slightly obscure. Later in Operation SALAMANDER (originally called DENHAM), he would return to Poland under the guise of Captain Edward Paisley (TNA HS9/1137-6) and return on operation WILDHORN III (Link: Wildhorn). Kot also spent time in the Middle East as a Minister of State and indicated his extended period there was to avoid any embarrassment to Sikorski over Premier Mikołajczyk’s relationship with him (TNA/HS4-143).

Continental Action was not a ‘side-show’ despite the main subversion thrust through the AK in occupied Poland. The use of the Cichociemni proved to be more effective both politically and militarily giving an advantage over the Germans through their specialist skills employed there in supporting the AK. Nevertheless, the quality of intelligence and sabotage played a crucial role prior to operation OVERLORD in France by the Cichociemni sent there. Group or individual acts of heroism should not be forgotten or undervalued within the context of Continental Action as it formed an effective transnational resistance in many Axis occupied countries.

The first attempt to infiltrate Cichociemni as part of Continental Action was a ‘trial run’ to France and the Bordeaux area that ended in disaster. A Whitley V (T4165) from RCAF 419 Squadron took off from Stradishall in Suffolk on 11th April 1941 on Operation JOSEPHINE in a planned attack on the Pessac electrical transformer plant. A second attempt in June 1941 JOSEPHINE B was successful and limited submarine base operations for weeks (Livingstone, ND). The Whitley was piloted by Fl. Lt. A.J Oettle and carried six paratroopers: Capt. Mieczysław Kalikiński, Lt. Kazimierz Bogdziewicz (who later was part of Operation MARKET GARDEN), Lt. Kazimierz Dendor (who later was part of Operation MARKET GARDEN), Lt. Stanisław Kruszewski (Stanisław Mazur) was the commander of the 8th Company (He was injured in a grenade training session before MARKET GARDEN and returned to Ringway as a parachute instructor), 2nd Lt. Władysław Miciek (who later parachuted into Poland as a Cichociemni), and 2nd Lt. Ludwik Zwolański (who later was part of Operation MARKET GARDEN) (Lorys, 1993; Grabowski, 2011). The drop was aborted over the Loire valley and returned to Britain whereupon it crash-landed at Tangmere at 03.20 with several injuries and aircrew killed (TNA/ AIR 81/5779).

Operation ADJUDICATE (Link: Adjudicate) is often listed as part of Continental Action although the operation appears to be semi-autonomous. Adjudicate (Count Dziergowski) had been parachuted into France by RAF 138 Squadron on 2nd to 3rd September 1941 in the vicinity of Limoges (TNA/ HS4-325). Despite injuries on landing, Adjudicate, was robust and recruited 180 interned Polish troops (M.R.D. Foot claimed it was only 87) into sabotage cells that was later compromised, and the mission abandoned in February 1942 as it placed the Polish diaspora at risk (Maresch, 2005a). The operation also threatened the security of Continental Action due to its overlap and therefore exposure of networks and cells in POWN and later MONIKA/ BARDSEA. However, Operation ADJUDICATE became the ‘blueprint’ for developing networks and cells using Poles in France and other occupied countries to form a transnational resistance throughout the Axis.

Offensive Military Operations:

By November 1942 Jerzy Jankowski (Dominik) headed 500 personnel and 31 Stations reported to II Bureau from France and Belgium while civilian led networks covered Denmark and Sweden (Link: Scandinvian Connection). Within the planning for D-Day (OVERLORD), the need for detailed mapping of defences and development of diversionary operations led to the Special Affairs Department (WSS) at the Polish Ministry of National Defence initiate the next phase of planning (Pepłoński, 2005). Details of the ‘Atlantic Wall’ had been provided by members of the ‘Musketeers’ (Link: The Musketeers, Intrigue, and the Balkan Connection) After a period of training personnel in Britain, 15 landing sites in France were selected for the dropping of agents between July 1943 and August 1944 where fifteen drops were made with additional supply drops made by parachute.

The operation was in two phases: The first was for the collection of information by Polish organisations based in France through POWN after operation ADJUDICATE was compromised. The second phase was a new network collecting information on garrisons, fuel and munition depots, fortifications, airfields, and protection of transport networks under the guise of MONIKA. Station Interallié worked closely with French intelligence headed by Capt. Roman Garby-Czerniawski and Mathilde Carré within the Vichy zone in Toulouse. He was arrested by the Abwehr and ‘turned’ to collaborate with the Germans (Pepłoński, 2005). On arrival back in Britain, Czerniawski (code name Brutus by the German) he worked as a double agent for MI5 providing false information as part of operation FORTITUDE SOUTH.

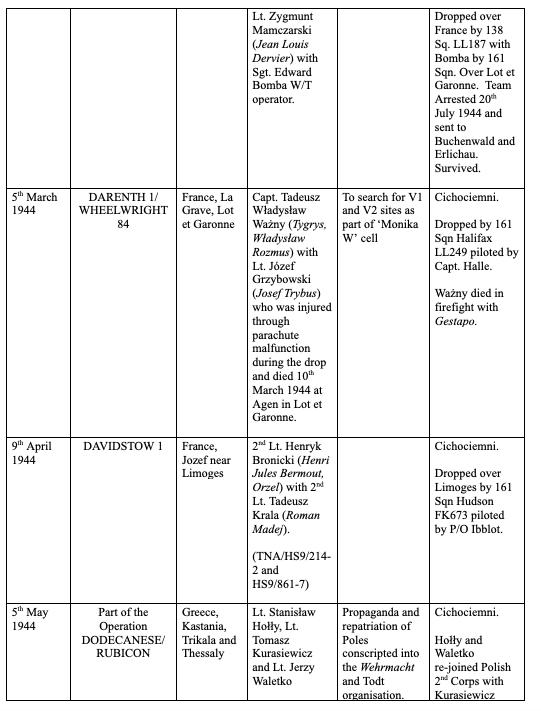

Intelligence gathering for the imminent invasion of France was led by Capt. Tadeusz Władysław Ważny (Tygrys, Władysław Rozmus) who was parachuted into France on 5th March 1944 by 161 Squadron (Operation DARENTH) and trained as a Cichociemni (Lorys, 1993). His operational area was Armentières-Bruay-Arras-Cambrai area (Pepłoński, 2005; Rowiński, 2016) particularly searching for V1 and V2 sites as part of ‘Monika W’ cell (Pepłoński, 2005). This group were later accredited with destroying two launch ramps for V1’s in the Douai area. Altogether, his team which included Capt. Mieczsław Golon (Michel) identified 59 launch sites and the construction site for a V3 artillery cannon in the Mimoyecques area in northern France. They also reported on troop distribution and movements, coastal defences, and location of unit HQs with sketches and diagrams to assist intelligence analysis (Pepłoński, 2005). Capt. Golon was later killed while resisting arrest by the Gestapo. Arrested at the same time was Stanisław Łukowiak who liaised with the French Resistance and was a local tailor who was deported to Sandbostel and died there. He was the father-in-law of Mieczsław Golon. Their bravery and actions saved thousands of lives in southern Britain. The Monika operation was wound up on 28th August 1944.

The centre of ‘Continental Action’ was run out of neutral Portugal (Link: Polish Intelligence Operations in Portugal). Col. Jan Kowalewski was an outstanding intelligence officer and cryptologist who had also participated in the Third Silesian Uprising in 1921. He had postings as a military attaché to Moscow and Bucharest prior to the outbreak of war. He was in the guise of a director of Tissa the state-owned enterprise procuring materials for Poland’s armaments industry and linked to II Bureau (Ciechanowski, 2005b). After the fall of France, Kowalewski (Pierre) made his way to Portugal to work with refugees located in Figueira da Foz area and then Lisbon. Kowalewski also organised his own lines into France and had two W/T sets infiltrated (TNA/ HS7-183) to support these escape lines communications.

Source: N/K

In Lisbon, he met Jean (Ioan) Pangal, a Romanian Envoy and old acquaintance. Kowalewski tried to persuade Pangal to negotiate with Romania, Hungary, and Italy to join the Allies (Ciechanowski, 2005b). Pangal had the resources and contacts to support aid to the refugees too and persuaded Kowalewski to remain in Portugal with Gen. Władysław Sikorski’s approval. Through diplomatic channels Kowalewski contacted Marshal Antonescu of Romania, Admiral Horthy of Hungary, and an Italian diplomat Dino Grandi (Dubicki and Dubicki, 2019). The extent of his work emerged at the conference at Casablanca in 1943. Stalin vexed by Kowalewski’s anti-communist stance and known objector to the post war Soviet expansion into central and eastern Europe, became a persona non-grata. Kowalewski was seeking a post-war anti-communist federation of Central European countries to block Soviet expansion that antagonised Churchill too (Dubicki and Dubicki, 2019).

Jean (Ioan) Pangal. Source : N/K

Kowalewski was appointed as chief of the ‘cell’ for communications in Lisbon under the identity of a ‘correspondent’ attached to the Polish Interior Ministry as his cover due to the level of German intelligence gathering within Portugal (Dubicki and Dubicki, 2019).

Continental Action had emerged from plans made by Jan Librach and Prof. Stanisław Kot with further recommendations from Kowalewski incorporated into the final plan and to be based in Portugal to exploit its neutrality (Ciechanowski, 2005b; Maresch, 2005b; Dubicki and Dubicki, 2019). Portugal also had a low level of penetration by Soviet intelligence giving the Poles a strategic advantage. Kowalewski rented a villa Grinalda in Monte Estoril, just outside Lisbon where the radio communications equipment was set up. Kowalewski and his family lived in a boarding house in the centre of Lisbon and there were another three ‘safe’ houses used to camouflage his activities (Ciechanowski, 2005b).

Based on: https://elitadywersji.org/en/akcja-kontynentalna/; http://www.plan-sussex-1944.net/anglais/pdf/infiltrations_into_france.pdf; https://harringtonmuseum.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Carpetbagger-planes.pdf , Grabowski (2011) and selected files from TNA HS4/141 cross referenced to SOE database.

Continental Action missions also covered intelligence on key installations of Romania’s oil and refinery industry (Dubicki, 2005) that resulted on the mass raids on Ploiești in August 1943 that put them out of action for many months. It was the diplomatic element of Continental Action under Operation TRIPOD that was more successful, and this is covered in the covert economic, political, and diplomatic section.

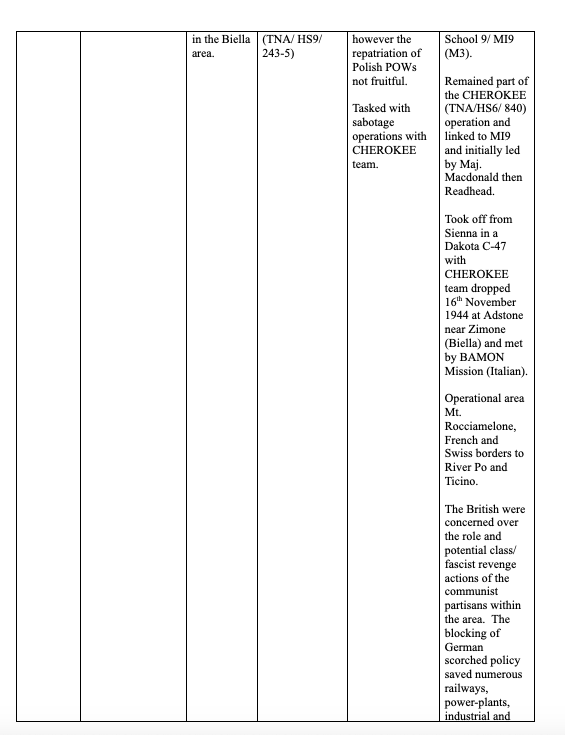

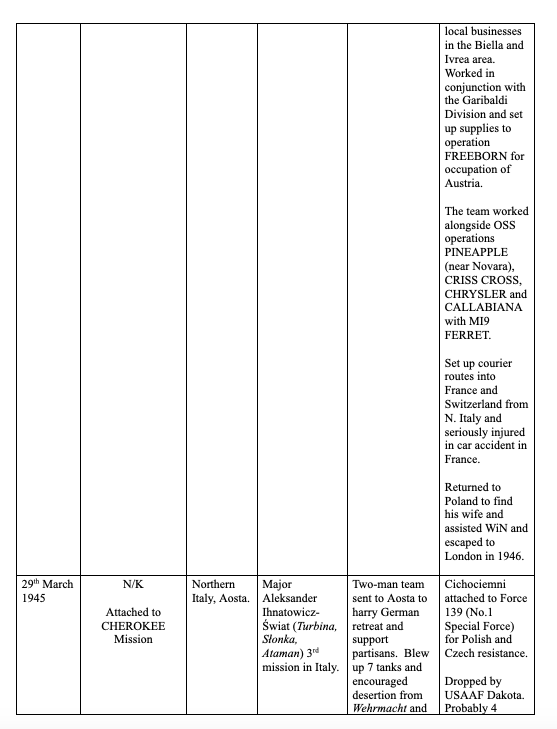

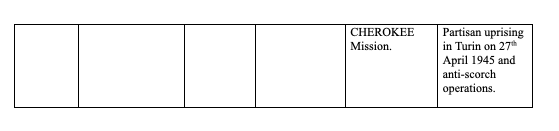

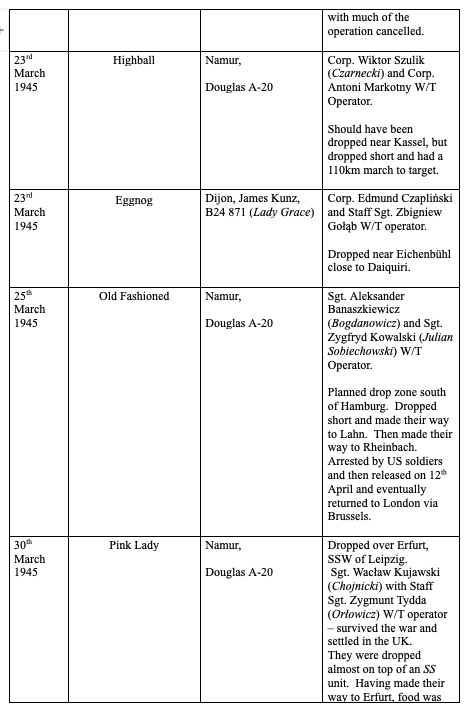

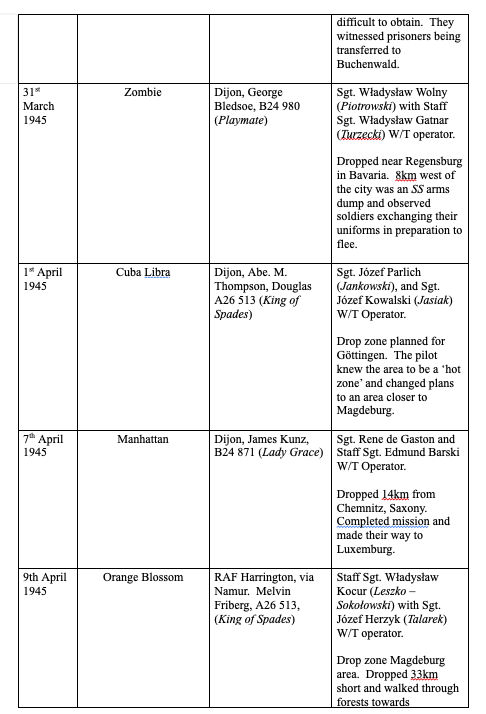

Project EAGLE (not to be confused with an OSS mission in Korea) was the last major contribution to Continental Action that lasted between March and April 1945. Forty Polish volunteers who were former conscripted Wehrmacht troops captured just after D-Day. They joined the Cichociemni training programme in Scotland using Arisaig House (STS 21), Garramor (STS 25) and completed parachute training at the Polish section at Manchester Ringway with the core training completed in 3 months including radio communications. Thirty-two were successfully chosen for the operation and would work normally in two-man teams reporting on troop locations, movements, and state of the soldiers’ morale. They used cocktails as their mission names (Micgiel, 2019). Many were given false identities in case of capture and paid a Dollar bounty for their risks, but not given Cichociemni status. The recruits were mainly from the former border areas of Silesia, Pomerania, and Greater Poland (Micgiel, 2019) and would be in a better position to survive the turmoil in Germany as the war was close to a conclusion. OSS had discussed with SOE the infiltration of agents way back in 1942 (TNA/ HS4-143).

The agents were mostly transported to Dijon in France and Namur in Belgium and then dropped into Germany from OSS ‘Carpetbaggers’ operated B24 Liberators adapted to these types of missions flying close to the ground to avoid night-fighters and then drop the agents from 600 to 800ft. The adaption of the B24’s was mainly the removal of the ball turret and the nose gun. The agents and their mission locations appear to be partially linked to their ethnic origins for additional cover.

The Allies had crossed the Rhine in March 1945 (Operation LUMBERJACK and UNDERTONE) with Soviet forces pushing through eastern and central Poland towards the river Oder. Although this highly secret operation had successes, the potential for capture was high and its effectiveness should not be underestimated despite the chaos of the collapsing Reich.

and Szyprowski (2023)

The teams were working in difficult conditions and poor circumstances where collected intelligence could not always be easily relayed, and reports were often handed to advancing Allied units who were in disbelief they were an OSS operational unit. Dressed in civilian clothes and passing off as German civilians, the risk of being shot was high. The zones they operated in were the last strongholds of the Reich where food shortages and chaos caused by civilian evacuations made the operations more hazardous. The ‘death marches’ of POWs and inmates from labour and concentration camps needed verification. Control of the civilian population was also in chaos with Volkssturm acting as militia and not always checking documents of refugees that gave some teams like ‘Zombie’ an advantage. W/T equipment could easily be rendered useless due to the lack of electricity to re-charge batteries. The Project EAGLE teams witnessed the ‘death-throws’ of the Reich with some of the teams participated in searching for Nazi war criminals and the dreaded Gestapo after their missions were completed.

Offensive Political, Economic and Diplomatic Operations:

Kowalewski (Pierre, Piotr and later Nart) linked the work of Continental Action with the Polish Interior Ministry in cooperation with the British Ministry of Economic Warfare (Ciechanowski, 2005b). II Bureau also had offices attached to the legation in Portugal. Initially, the focus was on contacting Polish resistance movements in France and intelligence gathering on the political activities of the Axis in Portugal through courting diplomats. SOE had an office in Lisbon run by John G. Beevor between 1941 and 1942 and he kept close contacts with Kowalewski who had unearthed the location of a German radio station monitoring allied shipping and relaying co-ordinates to the U-boat fleet in the north Atlantic. The location was between Cascais and Cabo Raso (Ciechanowski, 2005b)

Such was the quality and level of Kowalewski’s work that Brigadier Gubbins and the USA praised his achievements (Dubicki and Dubicki, 2019). In 1942 there was a shift in the intelligence strategy to destabilise the Axis through covert negotiations with diplomats attached to the Hungarian, Romanian and Italian governments under operation TRIPOD. Operation TOPAZOWICZE (TOPAZY) was directed at the Hungarians who were more enthusiastic of the three willing to co-operate. When pro-allied Miklós Kállay von Nagy-Kálló became prime minister, it gave him an opportunity for a secret ceasefire convention on 9th September 1943 that indicated Hungarian troops would surrender to Allied, not Soviet troops on the assumption the Allies would enter the country through the Balkans. The agreement was tactical politics at its worst since the Allies were not able to support the ceasefire. Roosevelt and Churchill opposed the Balkan Front plan that had been ‘floated’ by Kowalewski. Hitler was incensed when informed and set out a plan for operation MARGARETHE for the occupation of Hungary in March 1944. Nagy-Kálló feared the Soviets, however the Hungarian Army was insufficient to oppose the Reich alone and was forced to negotiate with the Soviets in early 1944 since the Allies were politically and geographically too distance to lend support.

The unconditional surrender of Italy in September 1943 certainly simplified negotiations but did not mitigate the severe degree of German action towards the Italian civilians and partisans or indicate the bloody conflict that would emerge in clearing the Germans out of the country

Contacts within Romania stretched to their leader, Marshal Ion Antonescu who had a predisposition to common interests held by Sikorski and Kowalewski. Kowalewski was highly regarded in his role in pre-war time Bucharest that had paid off (TNA/ HS4-261). With an increasing number of defeats suffered by the Reich, Kowalewski’s use of propaganda and his personal contacts with opposition politicians, destabilised the Axis which included not to participate in crimes against humanity and restrict troop deployment to the Eastern Front (Ciechanowski, 2005b).

Kowalewski’s efforts had been thwarted in January 1943 when the meeting in Casablanca settled on ‘unconditional surrender’ of the Axis powers. Kowalewski’s promoted idea of opening a second front in the Balkans that would have a domino effect on the Axis powers loyalty to the Reich lost ground. Blocking Sovietisation of eastern and central Europe – one of Kowalewski’s key themes found no favour with the Allies. Stalin was against these negotiations and as a result, only approaches to the Italians were permitted to continue. Contacts with Hungarian and Romanian emissaries was severely reduced. By the summer of 1943, the concessions to Stalin and the Sovietisation of the Balkans began to impede any negotiations underway. The action by King Michael I of Romania when he considered exile, left Marshall Antonescu in a more perilous state that resulted in loss of enthusiasm for Kowalewski’s plans (Dubicki and Dubicki, 2019). Kowalewski’s position became increasingly untenable since Stalin made it known to the leaders of the Allies that Kowalewski’s anti-communist stance and known objector to the post war Soviet expansion into central and eastern Europe was an impediment to resolving the future settlement of post war Europe between the Soviets and the Allies (Dubicki and Dubicki, 2019).

While Romanian diplomats sought to seek an exit from the Axis, they added conditions of a triple occupation by the Allies and the Soviets. They would only capitulate if there was no German occupation. The outcome was for Poles and Romanians acting as emissaries to withdraw from negotiations (Dubicki and Dubicki, 2019). Only the 1944 Romanian coup d’état on 23rd August which deposed Ion Antonescu, enabled King Michael I to seek an armistice and re-alignment of his forces under the Allies that fomented further unravelling of the Axis.

Kowalewski’s operation began to rankle the British government too. Sir Alexander Cadogan, the Foreign Office’s Permanent Under-secretary of State, requested Ambassador Raczyński to recall Kowalewski based on his ‘alleged’ contacts with Germans in Lisbon on 10th March 1944 (TNA/ HS4-144). It must be remembered Lisbon was the spy capital of Europe and Kowalewski operated within its ‘muddy waters’ encouraging dissent within the Axis. It was known Kowalewski had met German representatives on several occasions (Ciechanowski, 2005b) and reported to the Polish authorities as part of his intelligence gathering with examples of reports being shown to Lord Cadogan (TNA/ HS4-144). Despite Lord Cadogan’s stance over this ‘delicate situation’ (TNA/ HS4-144), Sir Frank Kenyon Roberts, a career diplomat and later Ambassador to Moscow during the ‘Cold War’, was a strong supporter of Kowalewski and the work he had carried out for the Poles and SOE (TNA/ HS4-144).

For Poles escaping Vichy France, evacuees were given Polish passports with a visa to some far-flung place to obtain a Portuguese transit visa (Richards, 2013) through Kowalewski’s network. Kowalewski had developed escape lines into both Portugal and Spain from France. In 1942 the escape lines were temporarily ‘frozen’ with Polish agents seeking SOEs assistance to return to Britain using fake British identities (TNA/ HS4-261). Some escapees obtained French exit visas in Perpignan and thence travel to Lisbon legally. Those who travelled without papers and visas found transiting Spain increasingly difficult since the Polish operation in Spain lacked a positive liaison role with SOE despite good intelligence being gathered (TNA/ HS7-183). (Link: Feluccas & the SOE). Many illegal Polish detainees escaping from camps in Vichy France were travelling on fake documents and those caught by the Spanish authorities were imprisoned in Miranda de Ebro with Spain refusing to return the escapees to the Germans. From March 1943, the defeat of the Nazis and the collapse of the Reich becoming increasingly a more likely scenario, Spain eased conditions on the Poles and started to release prisoners (Link: Miranda de Ebro) who made their way mainly to Gibraltar.

At the height of operations, Station ‘M’ had 67 agents supporting networks of couriers into France (Station F) and Portugal and although the station became subordinated to Station ‘P’, managed to run three cells. Cell no. 2 headed by 2nd Lt. Włodzimierz V. Popławski (Paul) an experienced agent who had been in Spain during the civil war provided good quality intelligence reports worked on the evacuation of escaped Poles. Cell no. 3 (Naval) was headed by Capt. Roman Koperski (Torero) who was caught on 6th January 1942 and imprisoned for spying for Britain against the Spanish and Germans was eventually released at the beginning of 1944 having avoided the death penalty (Ciechanowski, 2005a). Cell no. 7 in Barcelona was also involved with assisting escapees and headed by Wanda Halina Morbitzer-Toza (Ewa) until her arrest in 1943. Her work included liaison work for SIS and managed to flee to Portugal before her formal arrest (Ciechanowski, 2005a). Cell no. 1 covered activities in Rome.

E/ UP worked closely with II Bureau and VI Bureau who briefed agents on their missions. The escape and evasion lines from France into Spain were also used in reverse to infiltrate agents. Lt. Władysław Galica who also used the nom de guerre Capt. Fedro (Tok, J.M. Roger) used the Lasalle Line most likely developed by Kowalewski who liaised with Section F of SOE (TNA/ HS7-184) to enter France in January 1944 (TNA/ HS4-273) in Operation LABURNUM. He was accompanied by L/Cpl. Adam Staffij (Dule, T. Swiecicki). Both were flown to Gibraltar under the guise of 2nd Lt. Joseph Batterdale and 2nd Lt. Augustus Jessop. Galica’s training report from S.T.S No. 24b (Glaschoille, near Inverness, Scotland) on 21st April 1943 indicated good field craft, combat and shooting skills, however W/T training was poor hence the need for a W/T operator to accompany him. Rated as an ideal leader, it was recommended he should be assigned to solo work in the field due to personality traits (TNA/ HS4-260). Galica had been trained as a Cichociemni (Badge no. 0158/1500) (Link: Cichociemni). Adam Staffij (Badge no. 2664) was seconded from the 1st Polish Parachute Brigade (Lorys, 1993).

There were also semi-autonomous evasion lines. One was run by Capt. Andrzeja Wyssogotę -Zakrzewski (Visigoths-Lorraine line) operating in the Marseilles area who assisted in intelligence gathering, subversion and the evasion of Polish soldiers and allied pilots to north Africa through the Pyrenees, Spain, and Portugal (Bielak, 2019). Little is known about the organisation; however, civilians were evacuated too. It is understood the evasion line stretched into the Netherlands as part of the Dutch-Paris Line. Capt. Wyssogotę-Zakrzewski and a Dutchman Thijs were caught in a roundup by the Gestapo in November 1943. The evasion line was later infiltrated and collapsed in March 1944.

It seems in 1945 the British had forgotten Kowalewski had reported to both the Polish Government in Exile and the British Government that a meeting with Hans Lazar and Capt. Fritz Kramer of the Abwehr had tipped him off over Germany’s plan to attack Soviet Russia in operation BARBAROSSA (Ciechanowski, 2005b). Was the demanded recall to London to protect Soviet-British relationships or was it an indication that the British Government was tiring of the ‘Polish Question’ and its ‘First Ally’? Certainly, the diplomats within the FO thought otherwise. Sir Frank Kenyon Roberts questioned the decision as these meetings had been fruitful in ‘taking the pulse’ of German diplomats at this crucial stage of the war. Kowalewski flew to Britain on 5th April 1944 (TNA/ HS4-144) that broke a vital link to operation TRIPOD and CONTINENTAL ACTION (TNA/HS4-144). Kowalewski’s career was not over. He had a significant role as Chief of the Polish Special Operations in the preparation of D-Day as a co-ordinator for sabotage and diversionary actions by operation MONIKA. (Link: Operation Monika)

Postscript:

As the war ended, the achievements of Poland’s forces, particularly the Cichociemni and the successes of Continental Action was flagged up by SIS as a major concern surrounding the relationships with the Soviets. SIS were concerned that files and technical information of the Polish Section of SOE (E/UP) and VI Bureau would end up in Soviet hands (Tebinka, 2023). Indeed, there was a pro-active resistance for any assets of the government-in-exile to be transferred to the Soviet ‘puppet’ government in Poland (Rogalski, 2017) resulted in records held at Poland’s intelligence HQ (St. Paul’s School in London) substantially destroyed. In an attempt at appeasement, Premier Mikołajczyk flew to Moscow to confirm acceptance of the ‘Curzon Line’ (TNA/ HS4-139) that turned out not to be settled but seen as an interim agreement by Stalin. Britain feared any action by EU/ P in the closing stages of the war might antagonise the Soviets and the Lublin Government. EU/P activities and diplomatic bags were being monitored and controlled (TNA HS4-166; Rogalski, 2022) to minimise any diplomatic tension. Fears of the NKVD’s campaign of arrests, torture, and deportations of former AK officers (TNA/ HS4-140) were realised, leaving many former soldiers and politicians lives at risk with their contributions as the ‘First Ally’ often overlooked in the main dialogue in the closing stages of the war and initial post war period.

Certainly, internal political intrigue surrounding the Polish Government-in-Exile was time consuming (TNA/ HS4-141) and a drain on its effectiveness to govern due to the complexity of the parties and its ‘unity’ (Stola, 2012). Continental Action was geographically dispersed through many occupied countries at great risk to the missions and personal safety. In the closing stages of the war, the insertion of Polish Liaison Officers (PLO’s) provided critical military intelligence on the Wehrmacht’s withdrawal with tactical sabotage and propaganda to make the process of retreat more difficult and at the same time proved transnational resistance was an effective strategy. The sheer scale of these operations is often overlooked and yet the results were impressive, particularly in northern Italy, France, and the Balkans. The political propaganda and skills training for local partisan groups; the destabilising of German military units through encouraging troops to desert, needs to be given greater credit for the unravelling of Germany’s final grip on the occupied countries.

The treatment of Kowalewski was shabby and failed to give him credit for the outstanding role he played in seeking political solutions within operation TRIPOD and the effective use of ‘old school’ diplomatic contacts to act as back-channels. The destabilisation of the Axis accelerated the demise of the Reich. While Britain’s Foreign Office seemed to be an integral part of the de-recognition of the ‘First Ally’ in currying favour with the Soviets, the true enemy of Britain and central European countries went unchallenged until too late. The concept of the Allies being ‘war weary’ and concerned about the future of leading politicians facing re-election, pales into insignificance when measuring the true cost of post war rebuilding of Europe and the ‘Cold War’.

While Project EAGLE was almost one of the last special operations to land agents into the heart of the Reich, other operations such as VIOLET run by S.A.A.R.F to assist in the clearing of allied POW camps (Operation VICARAGE), Operation DUNSTABLE and S.P.U 22 (Special Planning Unit 22) run by the Poles had a similar role (Link: Operation Dunstable) in trying to save POWs from starvation and the chaos of the collapsing Reich. While Operation BARDSEA had been cancelled, many of the troops returned to the Polish Parachute Brigade and some were transferred to S.A.A.R.F operation VICARAGE (TNA/ HS7-184).

The final Cichociemni operation was STASZEK 2 on 26th December 1944. The team was tasked to set up communications under the advancing Soviet Army. Liberator BZ965 V of 301 Squadron flew the team to Szczawa close to the forest at Gorczański in southern Poland that was still secure from the advancing Soviet forces. The team was led by Zdzisław Sroczyński (Kompresor) who later joined NIE and then escaped Poland in the autumn of 1945. He probably completed the last secret mission to Poland when parachuted back into Poland again a few months later probably on behalf of VI Bureau before its disbandment. Later operations were under the guidance of the CIA operating out of Mannheim in Germany and it is believed many of the former Polish SF officers continued with their clandestine work.

In their personal files (P/F’s) many of the Cichociemni dropped into France, northern Italy and the Balkans were recommended for British awards which were blocked. Their files were annotated ‘for political reasons’ and ‘hard core’. The explanation may be quite straight forward: the annotated files may mean these men were singled out as potential agents to be used in the ‘Cold War’. The debt owed to these gallant men should not be forgotten nor the role the First Ally’s significant role in major theatres of the war.

The unconditional surrender of Italy in September 1943 certainly simplified negotiations but did not mitigate the severe degree of German action towards the Italian civilians and partisans or indicate the bloody conflict that would emerge in clearing the Germans out of the country

Acknowledgements:

I would like to thank Dr. Steve Kippax and Clare Mulley for additional information relating to annotations in personal files held in Kew (TNA).

I would also like to thank George Cholewczynski (author of “Poles Apart: The Polish Airborne at the Battle of Arnhem” published in 1993) for correcting the details within Operation JOSEPHINE B.

Selected References

Bailey, R. (2020) “SOE and Transnational Resistance”, in Gildea, R. and Tames, I. (Eds) “Fighters Across Frontiers: Transnational resistance in Europe, 1936-48”, Manchester University Press, UK, Ch7, pp.132-154.

Bielak, M. (2019) “Ewakuacja żołnierzy polskich z Francji do Wielkiej Brytanii i Afryki Północnej w latach 1940–1941”, OBEP IPN, Poland.

Ciechanowski, J.S (2005a) “Iberian Peninsula”, in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch 24.

Ciechanowski, J.S (2005b) “Lt. Col. Jan Kowalewski’s Mission in Portugal”, in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch 54.

Dubicki, T. (2005) “Romania”, in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch 31.

Dubicki, A. and Dubicki, T. (2019) “Misja ppłk. dypl. Jana Kowalewskiego w Portugalii (1940–1944)”, Acta Universitatis Łodziensis Folia Historica, No.105, pp. 125-142.

Foot, M.R.D. (2004) “SOE in France”, Frank Cass, U.K.

Grabowski, W. (2011) “Agencie,” SOE? Polscy Spadochroniarze w okupowanej Europie”,

Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej” No. 8–9, Warszawa, pp. 98–107

Kajetanowicz, J. (2017) “Formacje wojsk specjalnych Polskich Sił Zbrojnych na Zachodzie i

formy ich wykorzystania przez rząd na uchodźstwie”, Res Politicae, No. 1, pp. 65-84.

Kochanski, H. (2012) “The Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War”, Allan Lane, UK.

Kruszewski, E.S. (1993) “Akcja Kontynentalna. Geneza. Założenia i struktura organizacyjna, w: Akcja Kontynentalna w Skandynawii 1940 – 1945”, Instytut Polsko – Skandynawski, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Livingstone, N. (ND) “Operation Josephine”, http://beforetempsford.org.uk/1941/04/ (Accessed 05.01.2024).

Lorys, J.J. (1993) History of the Polish Parachute Badge: Polish Airborne Forces in World War II”, Sikorski Institute, U.K.

Maresch, E. (2005a) SOE and Polish Aspirations”, in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch18.

Maresch, E. (2005b) “Special Operations Executive”, in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch14.

Micgiel, J.S. (2019) “Project Eagle: Polscy wywiadowcy w raportach i dokumentach wojennych amerykańskiego Biura Służb Strategicznych”, Kraków University, Poland.

Pepłoński, A. (2005) “The Operation of the Intelligence Services of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MSW) and of the Ministry of national Defence (MON)>, in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch11.

Rogalski, W. (2022) “Special Operations Executive: Polish Section – The death of the Second Polish Republic”, Helion & Co., UK.

Rogalski, W. (2017) “Divided Loyalty: Britain’s Polish Ally During the Second World War”, Helion & Co., UK.

Rogalski, W. (2017) “Divided Loyalty: Britain’s Polish Ally During the Second World War”, Helion & Co., UK.

Rowiński, B. (2016) “THREE OF THE “SILENT AND UNSEEN” PARACHUTED INTO OCCUPIED EUROPE”, in Proceedings of 2nd INTERNATIONAL MILITARY HISTORY CONFERENCE, Ch. 4, pp. 63-72.

The Polish Section of S.O.E. and Poland’s “Silent and Unseen” 1940-1945, “Cichociemni” - The Airborne Soldiers of the Polish Home Army A.K.

Soroka, W. (1976) “Professor Stanisław Kot: Scholar”, The Polish Review, Vol.21, No. 1-2, pp.93-112.

Stafford, D. (2011) “Mission Accomplished: SOE And Italy 1943-1945”, Random House, UK.

Tebinka, J. (2023) “End of Anglo-Polish Cooperation in Special Operations between April and December 1945”, International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 121-139.

Tochman, K.A. (2007) “Słownik Biograficzny Cichociemnych”, Vol. II, Ostoja, Poland.

Additional References:

Anon (1987) “No.1 Special Force and Italian Resistance”, Proceedings of the Conference University Bologna, Italy.

Dvorak, D.F (2015) “USAF Special Operations Heritage: Colonel Cliff Heflin and his WWII Carpetbaggers”, Air Power History, Vol.62, No.1, pp.16-29.

Królikowski, H. (2016) “Operacja Adolphus: pierwszy zrzut Cichociemnych Spadochroniarzy AK”, Defence 24, Wydział Studiów Międzynarodowych i Politycznych: Instytut Bliskiego i Dalekiego Wschodu, Poland.

Librach, J. (1973) “Nota o "Akcji Kontynentalnej", Zeszyty Literackie”, Paryż: Instytut Literacki, pp. 161-162.

Moore, BV. (1992) “The Secret Air War Over France" USAAF Special Operations Units in the French Campaign of 1944” Air University Press Maxwell AFB, USA. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA425597.pdf

Parnell, B. (1987) “Carpetbaggers: America’s Secret War in Europe”, Eakin PR, USA.

Persico, J. (1979) “Piercing the Reich”, Barnes & Noble Imports, USA.

Swearngin, P. (2009) “The Carpetbagger Project: Secret Heroes”, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, USA.

Szyprowski, B. (2023) “O konicarpetbaggers czności weryfikacji źródeł historycznych. Recenzja książki Kacpra Śledzińskiego Cichociemni. Elita polskiej dywersji”, Glaukopis, No. 40, pp. 452-484.

Selected Websites:

https://fundacjacichociemnych.pl/lista-cichociemnych/

whttps://elitadywersji.org/en/akcja-kontynentalna/

http://cichociemni.edu.pl/en/home/

https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Cichociemni

http://ww2talk.com/index.php?threads/soe-partisan-drop-zones-in-italy-austria-balkans-1944-45.57616/

Outline story on Lt. Henryk Śreniawa-Saganowski (Ibis, Huss and Ikar)

https://naszahistoria.pl/balkany-wlochy-francja-palestyna-nieznane-szlaki-cichociemnych/ar/c15-17720955

Outline story on Lt. Henryk Śreniawa-Saganowski (Ibis, Huss and Ikar)

https://www.polityka.pl/pomocnikhistoryczny/1658474,1,okolicznosci-powstania-projektu-sabotazu-i-dywersji.read

https://krotoszyn.naszemiasto.pl/ppor-stanislaw-lukowiak-czlonek-ruchu-oporu-we-francji/ar/c15-7682755

https://www.rafcommands.com

https://polishhistory.pl/project-eagle-polish-intelligence-agents-in-reports-and-documents-of-the-american-office-of-strategic-services-oss/)

https://www.criticalpast.com/video/65675072308_Project-Eagle_Office-of-Strategic-Services_Soldiers-of-Poland-in-Exile)

https://polishhistory.pl/this-is-not-a-grand-history-of-the-second-world-war/

Project EAGLE

https://codenames.info/operation/carpetbagger/

https://arsof-history.org/articles/v3n1_supplying_resistance_page_1.html

Records of OSS 1940 – 1947 that have been released.

https://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/Visit/Museum-Exhibits/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/195994/operation-carpetbagger/%23:~:text=From%20January%201944%20to%20May,Joe%20Holes%20into%20enemy%20territory

https://www.businessinsider.com/operation-carpetbagger-snuck-oss-secret-agents-into-france-during-wwii-2020-9?r=US&IR=T

List of Carpetbaggers planes and crews with other notes.

https://dziennikzbrojny.pl/artykuly/art,2,4,4811,armie-swiata,wojsko-polskie,historia-i-tradycje-polskich-saperow-czesc-trzecia

http://www.419squadron.com/cbmain.html5

https://beforetempsford.org.uk/

OSS Chrysler Mission

https://www.nps.gov/articles/OSS Operationsm

https://www.militaryhistoryonline.com/WWII/SAARF

Selected Films, and You Tube Clips:

project-eagle original footage.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KPd20C3sNEg

The Carpetbaggers

S.A.A.R.F Operation VIOLET

|

|