Katyń Forest Massacre 1940

(zbrodnia katyńska)

Introduction

Eighty-two years after the discovery of the Katyń Forest Massacre, controversies surrounding who the perpetrator was has been explored by numerous authors such as: Lukas (1990); Thompson (1990); Davies (2003); Williamson (2009); Kochanski (2012); Rogalski (2017); and Moorhouse (2019) where there is conclusive evidence of the Soviet complicity (Komaniecka, et al, 2013; Urban, 2020) despite effective propaganda wars between the Nazis and Soviets deflecting the Allies attention, particularly the exiled Poles to the crimes committed by both sides (Thompson, 1990; Davies, 2003, Kochankski, 2012; Rogalski, 2017). The effectiveness of the propaganda by the Nazis and Stalin’s lies potentially weakened the Allies who largely played down the impact of the massacre since it threatened the more important alliance with Moscow (Komaniecka, et al, 2013). Furr’s treatise (2013) as an addition to the debate raised interesting points, the approach caused some angst amongst the Polish diasporas and surviving families. Parallels to the contemporary conflict in the Ukraine cannot go un-noticed, however Roberts (2022) suggests the NKVD’s records of 21,857 murdered Poles in Katyń and camps or prisons in the Ukraine and Belorussia should not be compared in ‘great detail’ to the contemporary conflict in the Ukraine. However, there is historical evidence that Soviet military indoctrination against the Poles dates back to the Bolshevik Revolution (Karski, 2012) that gives a partial explanation to the atrocious behaviour and the level of genocide committed prior to and during the Second World War (Karski, 2013; Mockaitis, 2022)

TNA/HS4/137

Chronology of events and locations:

The Soviet invasion was not well synchronized along the 1,400 Km border which started at 02:00 and 04:00 on 17th September 1939 (Williamson, 2009). The Soviet invasion was under the pretext of protecting the ethnic minorities in Eastern Galicia since the Polish Government had collapsed (Kochanski, 2012; Rogalski, 2017) even though it had relocated to its south-eastern border with Romania (Williamson, 2009). Defending the eastern frontier was an army of 100-150,00 troops poorly armed and largely made up of reservists and members of KOP, the border militia who fought on since there was little option in negotiating a safe passage to Romania (Williamson, 2009). Voroshilov’s ‘Lightning War’ may not have met widespread Polish defence; however, the Soviets met some significant engagements that highlighted overconfident leadership, poor planning, and inadequate logistical support (Hill, 2014). While the Soviet army had been partially mobilised, the speed of the German advances shocked the Soviets (Moorhouse, 2019).

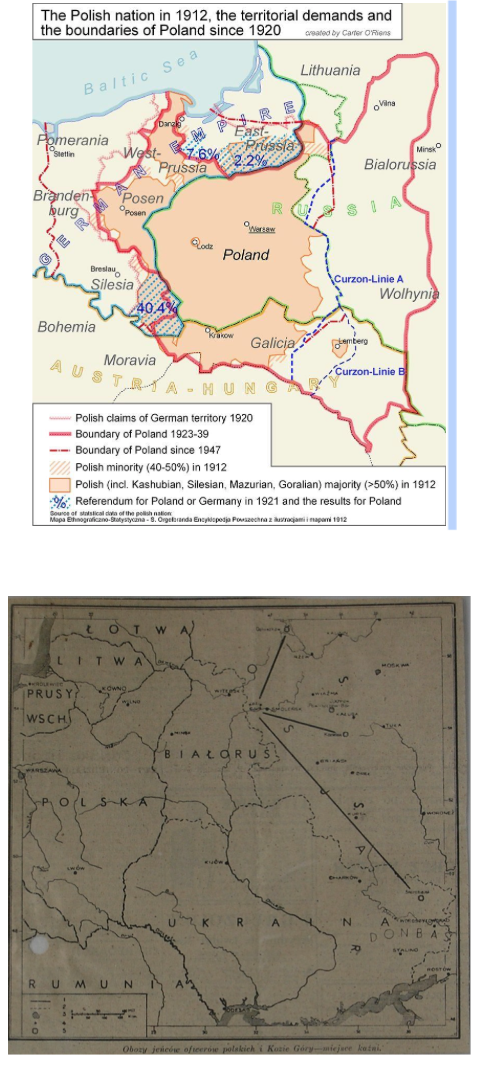

If the Soviets were ‘rescuing’ the Poles, why were the deportations and mass murders committed? The ‘Polish Question’ had dogged politicians both during war and at the Treaty of Versailles (Kochanski, 2012) on the future shape of Poland’s borders, particularly with Germany. Several options faced the Entente where the focus on internationalising the Vistula to give Poland access to the sea at Danzig (Gdańsk) (Kochanski, 2012) resulted in the Polish Corridor as a compromise that would have far reaching consequences in the eyes of the newly elected Adolph Hitler (Moorhouse, 2019) despite the issue being settled in Article 104 of the Treaty of Versailles (Kochanski, 2012). While Britain had lobbied for the Curzon Line to be adopted to delineate the eastern border giving some recognition towards independence of Lithuanian, Belorussian and Ukrainian interests (the area known as Kresy), Piłsudski’s land grab and Polonisation infuriated the local populous (Rogalski, 2017) with new landlords taking the more fertile land.

The region of Kresy became symbolic of Poland’s past greatness that Piłsudski was reluctant to forego (Kochanski, 2012). Although Lewis Namier, a Pole of Jewish descent who had been mistakenly attributed to the authorship of the Curzon Line, his anti-Polish views of encroachment into Kresy mirrored British Policy towards Poland and had little influence over Lloyd Georges government at the time (Rusin, 2013).

The Soviets saw Poland as a barrier to the expansion of communism that resulted in a disastrous war in 1920 with Piłsudski’s genius military stroke almost annihilating the Soviets at the gates of Warsaw – The Miracle on the Vistula. The Soviet losses were substantial with almost 10,000 killed, 30,000 missing and 66,000 prisoners. The Soviet army that attacked Poland was led by Vladimir Lenin who suffered further defeats that resulted in peace treaties between the Poles, Soviets and the Ukrainians securing Poland’s eastern frontiers for the time being at the Treaty of Riga. The Soviets still ‘smarting’ from the defeat, started to undermine the Treaty of Riga by passing a resolution at the Cominton’s 5th Congress for East Galicia to be incorporated into the Soviet Union (Rogalski, 2017). The regional Commissar, Josef Stalin tried to cover his failings in the defeat through using Lord Curzon’s proposals as a cover for political manipulation within the region (Rees, 2009). After 1921 specially trained groups of Ukrainian and Belorussian Bolsheviks and Red Army soldiers slipped over the Polish-Soviet border to attack local police stations and local administrators, causing damage until the formation of the KOP in 1924 restricted activities of the incursions (Komaniecka, et al, 2013).

Soviet policy towards Poland and the Poles until 1939 was based on undermining the Treaty of Riga and regain Eastern Galicia despite the matter being settled at the Polish-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact 1932 that had been under negotiation since 1926 (Kochankski, 2012; Karski, 2013; Komaniecka, et al, 2013). The Treaty of Riga like the Treaty of Versailles (1919) had left ethnic groups on the wrong side of borders. The Soviets had created two semi-autonomous ethnic regions: Marchlewszczyzna in the Ukraine and Dzierzynszczyzna in Belarus containing about 1m Poles who retained national and Catholic traditions that were incongruous to contemporary Sovietisation especially in the collectivization in the 1930’s (Komaniecka, et al, 2013). In 1936 Marchlewszczyzna was dissolved with the Poles deported to Siberia and Kazakhstan followed by Dzierzynszczyzna in 1938 with some 70,000 displaced Poles within the Soviet system. The Great Terror 1937-1938 impacted on not only the Ukrainians, but also the remaining Poles with the NKVD carrying out arrests and executions based on false accusations (Applebaum, 2003; Karski, 2013; Komaniecka, et al, 2013) in revenge for the Polish-Bolshevik war in 1920.

From the outset of the Soviet invasion on 17th September 1939, the Soviets started committing war crimes and deportations with a massacre at Grudno with captured Polish soldiers executed at Vilnius (Wilno) and Lviv (Lwów). Even surrendered Polish troops who had negotiated ‘safe passage’ towards the Romanian border were deceived. Behind the front specialist units of the NKVD were sweeping up Poles particularly the clergy, intelligentsia, and professionals numbering around 230,000.

Katyń

Camp Locations

|

Location

|

Type of Prisoners |

Numbers |

| Kozelsk:Former monastery |

Privates |

4,500 |

| Starobelsk:Former nunnery at 8 Kirov Street, 32 Kirov Street, 19 Wolodarski Street |

Scholars, priests, doctors, lawyers, journalists and 8 Generals |

8,894 |

| Ostashkov:Former monastery on island in lake Seliger 11km from Ostashkov |

State police and Military Police officials, secret service/ counter espionage agents, KOP. |

6,570 |

Based on Komaniecka, et al, (2013) and Urban (2020).

Places of Torture and Cemetries:

|

Location

|

Dates and Numbers |

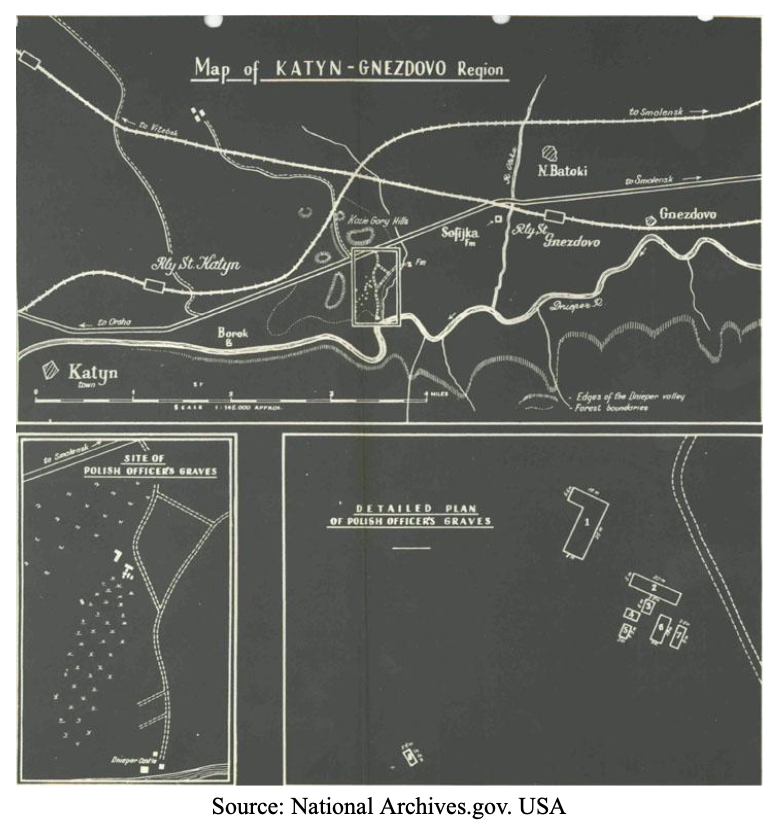

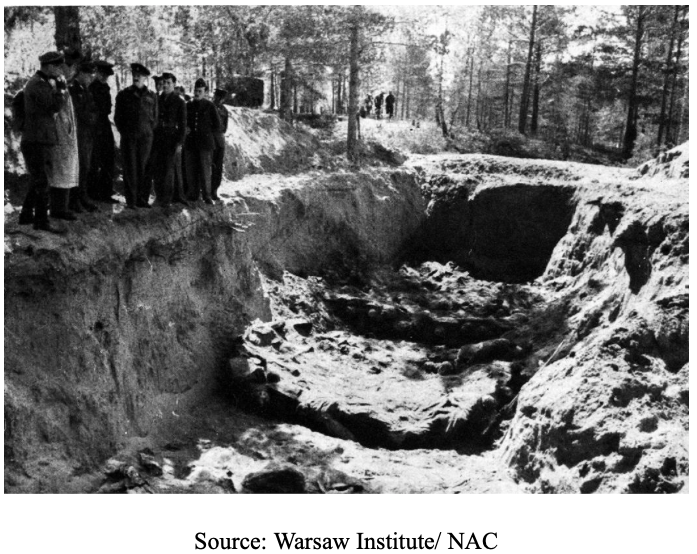

| Smolensk- Katyń |

3rd April 1940 first prisoners from Kozelsk taken to Kozie Gory death pits in the Katyń Forest. By 11th May 1940 4,421 citizens executed. |

| Kharkov-Piatykhatky |

5th April 1940 first prisoners from Kozelsk taken to the NKVD building in Dscherschinski Street basement and executed. Bodies taken to Forest Park in Kharkov about 1.5Km from Piatykhatky village. By 12th May 1940 3,820 executed. |

| Kalinin (Tver)-Miednoye |

4th April 1940 first prisoners from Ostashkov to 6 Soviet Street in Kalinin and executed in the basement. By 26th May 1940, 6,311 had been executed with bodies transported to death pits at Miednoye. |

| Bykivnia (Ukraine) |

1,980 Poles buried along with 150,000 different nationalities of victims of the NKVD. |

| Kuropaty (Belarus) |

Mass graves were discovered in 1988 containing 100-200,00 Belarusians, Jews, other nationalities including Poles – all victims of the NKVD. |

Based on Komaniecka, et al, (2013) and Urban (2020).

The Germans occupied the area around Smolensk from July 1941 until September 1943. On 13th April 1943, Berlin announced mass graves containing Poles had been discovered in the Katyń Forest. A team under Professor Gerhard Buhtz started to identify the victims whose names were published in Polish-language German press (Komaniecka, et al, 2013; Urban, 2020). Immediately Stalin refuted any claims to the atrocity and blamed the Nazis of mass murder that resulted in the Polish Red Cross (PCK) being invited on 16th April to participate in the investigation. Stalin’s outrageous behaviour included accusing the Polish Government in Exile of collaborating with the Nazis that resulted in the Soviets ‘breaking off relations’ with the Polish Government in exile (Komaniecka, et al, 2013; Urban, 2020).

The ‘technical’ commission consisted of the following:

1) Belgium: Dr. Spelers, Professor of Opthamology an the University of Gent.

2) Bulgaria: Dr. Markov, Forensic Medicine and Criminology teacher at the University of Sofia.

3) Denmark: Dr. Tramsen, Prosector at the Institute of Forensic Medicine in Copenhagen.

4) Finland: Dr. Saxén, Professor of Pathological Anatomy at the University of Helsinki.

5) Italy: Dr. Palmieri, Professor of Forensic Medicine and Criminology at the University of Naples.

6) Croatia: Dr. Miloslavich, Professor of Forensic Medicine and Criminology at the University of Agram.

7) Netherlands: Dr. de Burlet, Professor of Anatomy at the University of Groningen.

8) Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia: Dr. Hdjek, Professor of Forensic Medicine and Criminology in Prague.

9) Rumania: Dr. Birkle, Forensic Doctor of the Rumanian Ministry of Justice and first assistant at the Forensic Medicine and Criminology Institute in Bucharest.

10) Switzerland: Dr. Naville, Professor of Forensic Medicine at the University of Geneva.

11) Slovakia: Dr. Subik, Professor of Pathological Anatomy at the University of Bratislava and Slovakian Chief of State Public Health Works.

12) Hungary: Dr. Orsós, Professor of Forensic Medicine and Criminology at the University of Budapest.

The report was published 30th April 1943 with clear guidance on how the soldiers had been murdered and the likely dates of between March and April 1940 based on the evidence found during the investigation (Komaniecka, et al, 2013; Petrov, 2019; Urban, 2020). Dr. Tramsen, a Danish member of the investigation was aware and briefed like the rest of the commission not to discuss findings with the Nazis to avoid propaganda by them. While some evidence included German manufactured ammunition that had been supplied pre-war to both Poland and Russia, the evidence was conclusive. What perpetuated part of the ‘Katyń Lie’ was Dr. Tramsen’s insistence that the report should be amended to “it is regarded as probable that the shootings took place between March and April 1940” which was never included (TNA HS4-212) in the final report, but sparked concerns in the British F.O to see if Dr. Tramsen had other views or information that had not been officially disclosed since the relationship with Moscow had high importance to the allies.

The Nazi propaganda machine had a ‘hollow propaganda triumph’. After the invasion in 1939 Einsatzgruppen units, military police, counter-partisan and the Security Service (SD) were active throughout Poland under operation UNTERNEHMEN TANNENBERG which included the extermination or shipment to labour camps of the intelligentsia including those who participated in pre-war uprising s in Silesia and Wielkopolska or the notorious SONDERAKTION KRAKAU which resulted in the arrest of 183 academics mainly from Jagiellonian University, but also from AGH University of Science and Technology; the Business Academy and the Catholic University of Lublin and the Stefan Batory University with transports taking them to Sachsenhausen concentration camp (Paczkowski, 2003; Kochankski, 2012; Komaniecka, et al, 2013).

Land grabs by Volksdeutache and displaced Romanians of German descent, deportations and theft had started in earnest in December 1942 with some 10,000 farms and 30 villages cleared by the SS in areas around Zamośc and Lublin with residents deported to labour or concentration camps such as Oświęcim and continued in many districts until March 1943 (TNA HS4-144). The German massacre in the Pripet marshes in July 1942 indicated the extent and scale in the involvement of the German army with the Police Battalion 15/III, SS, SD, Gestapo, and tank units participating (TNA HS4-212).

The Katyń Lie:

Such was the intensity of Nazi propaganda machine’s output and Stalin’s denials, lies and disinformation and despite the Allies had significant corroborated evidence, doubts remained in some circles in order to protect the relationship with Moscow. A muted response ensured the Allies relationship with Stalin remained intact (Gleason, 2016; Urban, 2020) at a critical point of the war, much to the chagrin of the Polish Government in Exile who could not comprehend the British Foreign Office stance on the matter.

To perpetuate the lies, deceit and disinformation, the discredited Soviet Commission led by Nikolai Burdenko reported the massacre occurred in the Autumn of 1944 (Komaniecka, et al, 2013; Gleason, 2014; Urban, 2020) with the Soviet version ‘tainted’ (Petrov, 2019). Notwithstanding the clear rejection of the commission’s findings, the Soviets tried to include Katyń linking it to Nazi war criminals in the Nuremberg trials in 1946 with little success and became part of the ‘Katyń syndrome’ throughout the ‘Cold War’ (Petrov, 2019) with outdated books still being published in Russia until 2003 (Komaniecka, et al, 2013). Somehow, the Soviets and Allies had almost erased Anders extensive research and reports on the treatment of Polish POWs and were convinced the missing officers had been executed at Katyń (Anders, 1949). While the Nazis were more public in their mass killings and reprisals on the Polish local populous, the Soviets used more covert or uninhabited remote areas to conceal their crimes (Paczkowski, 2019) making post war investigations more difficult as Poland was still occupied and run by Soviet sympathisers (Paczkowski, 2019).

The NKVD sought out and arrested anyone who was involved in the exhumation and examination of the death pits in Katyń (Komaniecka, et al, 2013) as continuation of the cover-up. When the Soviets entered Kraków on 18th January 1945, the NKVD sought out members of the AK and in March 1945 arrested Dr Jan Robel and his team followed by the writer Ferdynand Goetel, and Dr Marian Wodzinski who were tried for collaboration with the Nazis (Komaniecka, et al, 2013) while others managed to escape abroad.

The British stance is revealed in various reports held in the British National Archives (TNA). There is clear evidence that the Foreign Office (FO) lacked understanding in the exiled Poles situation over Katyń and the Curzon Line (TNA HS4-144). A FO circular (TNA HS4-137) gave a detailed and conclusive report in 1943 of the Soviet complicity (TNA HS4-144). Prior to his death, Sikorski had Anders with the help of the AK investigated surviving prominent POWs and officials in both occupied Poland and in Russian camps when forming plans to evacuate them to the Middle East. Their investigation indicated 190,584 personnel were deported and published their findings in a report dated 24th June 1941 (TNA HS4/137). While Sikorski pushed the FO to assist in forming an army under Anders, the Soviet’s complained Anders was reluctant to fight for them on the eastern Front. The Soviets were suspicious of Anders who was seen as a ‘reactionary’ whose proposed Division would be loyal to Sikorski or a future Poland outside Soviet influence (Kochankski, 2012; Rogalski, 2017; McGilvary, 2018).

The Soviet backed Polish Division led by Colonel Berling under the ‘spiritual’ guidance of Wanda Wasilewska had staged a ceremony of ‘taking the oath’ on 14th July 1943 in front of a team of international journalists. The communist division was well equipped and ready to join clearing out ‘Fascist aggressors’ in Europe (TNA HS4-137). Sikorski had no intention that the evacuated Poles to the Middle East would face Soviet indoctrination and this formed a series of issues that led to the breakdown in relations between the Soviets and the Poles from mid-1943. British relations with the Poles were made worse by the FO’s insistence the Poles handed over their ciphers and codes (TNA HS4-144).

In an unusual ‘twist’ to the Katyń lie (TNA HS4-140), a United Press International Correspondent named as H. Uxkull, based in Stockholm reported on 7th July 1944 that a Dutch underground paper had evidence from several German policemen who had participated in the mass murder and were bizarrely on holiday in Holland. They claimed the ‘Polish Officers’ were reportedly Jews dressed in Polish uniforms and killed by the Gestapo with the discovery being manipulated by Goebbels for the Nazi propaganda machine. If true, Uxkull felt there was sufficient weight in the claim and conveniently explained the size of the massacre but felt the disappearance of Polish officers was not resolved. Uxkull further suggested that the Polish officers had been transported to Siberia by the Soviets in 1939 and their whereabouts remained a mystery for which Uxkull gave no explanation. The report concluded the concept of ‘crime and guilt’ in Soviet Russia is very different from the Allies notion where the context of protecting the Soviet State through liquidation rather than a less dangerous individual who may be incapable of injuring the state and therefore given a different form of punishment. This approach by Uxkull seemed to be a convenient explanation for the Katyń massacre and the subsequent Soviet denials, further advancing the ‘Katyń syndrome’.

As sense of ‘closure’ arose through the investigation by the Polish Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) launched on 24th November 2004. Its aim was to end the lies and deceit over the Katyń massacre based on an assumption that it was a war crime and a crime against mankind that could still be prosecuted (Gabriel, 2008; Komaniecka, et al, 2013) and covered the period 1939 to 1990. By the end of 2012 2,887 witnesses mainly drawn from victim’s families had been interviewed. True to form, in 2005 the Russian Federation made available only 67 out of 183 volumes of Soviet investigation files from its archives and took until 2012 to release more files, leaving only 35 still classified which leaves the investigation still being conducted.

Additional Soviet Atrocities:

The Katyń massacre was not an isolated act by the Soviets. As the 1st Ukrainian and 1st Belorussian Front pushed west in the winter of 1943-1944 with the help of partisan units, operation BAGRATION under Rokossovsky’s command routed German Army Group Centre and the Soviet forces crossed the river Bug on 18th July and on the 29th of July 1944 reached the river Vistula (Davies, 2003).

At this stage of the war, the Polish-Soviet relationship remained tense and lacking in trust at Government and local levels due to numerous field reports from the AK indicating further localized atrocities between the Soviet forces and partisan operations against the AK (TNA HS4-138). However, a report dated 22nd June 1944 by a former POW, RAF WO. T. Storey (TNA HS4-138) indicated the poorly equipped AK relationship with the Soviet partisans was of ‘armed neutrality’. Storey reported that in his observations AK officers regularly met but had a very different agenda to the Soviet backed partisans who appeared to be better supplied. This led Storey to explain the logistics of arms drops to Poland by the RAF.

Unfortunately, the overall evidence is quite different. In a report (TNA HS4-133) there was clear evidence of widespread atrocities and threats to AK units especially in the east of the country (TNA HS4-138). Early indications showed the P.P.R (Polish Workers Party) and commanders of the People’s Guard had in July 1943 agreed in the liquidation of officers in the AK with the Central Committee asking for lists of leaders to be drawn up which was duly done. In Krasnostav, local chairman Josef Pobreziak had a list of AK in Lublin and further meetings provided lists for: Kraków, Białystok, Grodno, Płock, Częstochwa, Radom, and Końskie (TNA HS4-138).

During September to October 1943 threatening letters were sent to The Secret Army (AK) leaders and officers in the voivodships of Podlasie and Polesie with the warning “who is not with us is against us. Those who are not with us will be shot” (TNA HS4-133) with further follow-up operations by the People’s Guard against the AK where in the Lublin district the local battalion commander circulated posters calling on the local populous to destroy leaders of the “reactionary independence organization” under the slogan of “Down with the officers, the helpers of Hitler”. In the same month, communist detachments in the Grodno region (now Belorussia) carried out death sentences on Poles who were known to be hostile to communism. In Wilno (Vilnius) and Nowogródek (Navahrudak) Soviet Fifth Column detachments attacked local AK units demanding their acquiescence to the communists where refusal was assassination as in the case of the Trans-Niemen Battalion with ordinary ranks conscripted into the Soviet army. In Polesie, communist Fifth Columnists tested the ‘metal’ of the AK by inviting them to meetings in the surrounding forests where they disappeared and left no trace through an effective cover up of the atrocities.

On 28th February 1944 Soviet backed partisan units in the Łuków region in eastern Poland had been surrounded and disbanded by the People’s Guard with no reported loss of life. However, the fate of AK units was not always the same experience. On 30th January 1944 a Cichociemni officer BOMBA had disappeared and believed to be in Soviet hands. It was established that he had been taken to the Soviet HQ in Broniłsawka 42Km south-west of Warsaw, under instructions of General Newmanow and Colonel Bohun along with two officers and ten men of the local AK unit. At the same time Colonel Bohun visited the AK HQ and demanded disbandment or face liquidation which was resisted, and the fate of the unit is not recorded in the dispatch. Those Cichocemni who were caught up in the advancing Soviet Army faced summary execution or forced to spearhead attacks on heavily German fortifications (TNA HS4-138).

On 1st January 1944, the commander of the local AK at Przebraze, Colonel Maczynski whose unit had defended the village valiantly, was accompanied by Dr. Pieta and a local leader Lt. Drzazga from Łuck (Lusk) to attend a meeting to discuss co-operation between the local AK and partisans. The body of Colonel Maczynski was found by a patrol on 4th January. A few days later, on 8th January 1944 a patrol by the AK found the bodies of Dr. Pieta and Lt. Drzazga, both shot in the back of the head just 1Km from a Soviet camp. Such was the extent of Soviet aggression in the disarming and liquidation that it was suggested back on 29th March 1943 to send an Inter-Allied Mission to eastern Poland to observe and supervise operations.

As the front moved west through Poland detachments of the Polish People’s Army (Ludowe Wojsko Polskie) and Soviet forces liquidated local As the front moved west through Poland detachments of the Polish People’s Army (Ludowe Wojsko Polskie) and Soviet forces liquidated local AK units near Radomsk, Płock, Grójec, Garwolin, Radomsko, Iłza, Ostrów, Opatów, Busk, Kielce, Tarnobrzeg and Częstochwa, seizing arms and property with the People’s Guard liquidating ‘spies’ and informers in the villages of Okolbudy and Zapusty. Even the Polish Workers’ Party (P.P.R) assisted the Soviets and communists through the sentencing of Michael Karwacki to death and in Rzeszów the local leader of the P.P.R party ordered the death of Chłewicki on the grounds of collaborating with the Nazis. In Radom the commander of the AK Capt. Dabrowski was denounced to the Gestapo (TNA HS4-138) which showed an extraordinary level of duplicity. units near Radomsk, Płock, Grójec, Garwolin, Radomsko, Iłza, Ostrów, Opatów, Busk, Kielce, Tarnobrzeg and Częstochwa, seizing arms and property with the People’s Guard liquidating ‘spies’ and informers in the villages of Okolbudy and Zapusty. Even the Polish Workers’ Party (P.P.R) assisted the Soviets and communists through the sentencing of Michael Karwacki to death and in Rzeszów the local leader of the P.P.R party ordered the death of Chłewicki on the grounds of collaborating with the Nazis. In Radom the commander of the AK Capt. Dabrowski was denounced to the Gestapo (TNA HS4-138) which showed an extraordinary level of duplicity.

The extent to which the People’s Guard and communists were prepared to use local Poles including the P.P.R, underlines the extent to which not only lists of names drawn up, but also chilling threats or facing the reality of death. Those in lower ranks of the AK who were captured on the Polish-Belorussia border were interned initially at Milaszewo near the village of Nesterowicze (Nesterovichi) in the Grodno area (TNA HS4-138). As mass arrests continued by the NKVD of the 8th and 9th Infantry Divisions under General Halka, some 200 officers and 2500 O. R’s were detained in Majdanek, near Lublin, a former concentration camp while slaughter of the AK continued. The Government in Exile lobbied for the Allies to recognize the Home Army to be treated as combatants (under the Geneva Convention) (TNA HS4-139). Miedniki near Wilno held 5-7,000 men, and Lubartów, near Lublin held about 6,000 men mainly from Berling’s (now known as Zymierski’s Army) whom the Soviets were treating as treasonous. Another camp at Rembertów on the outskirts of Warsaw mainly held Volksdeutache.

Discussions set out on 7th April 1944, brokered by Britain’s Foreign Office between the Government in Exile, the Soviets and AK in the Wolhynia to form the 27th Wolhynia Division under local Soviet control. Their loyalty and overall control would be to the Polish authorities in Warsaw and London. It seemed a far-fetched proposition when considering the liquidation of AK units (TNA HS4-138 and TNA HS4-139). Despite the discussions including an inter-allied unit liaising with BLO’s in Moscow, the plan was possibly a mechanism for more members of the ‘secret army’ to be flushed out and dealt with. The degree of suspicion and distrust blocked the plan developing any further.

After the collapse of Operation TEMPEST (‘Rising 44), AK units encountered further Soviet hostility. Prior to the start of TEMPEST, the local commander in the Lublin area reported on 26th July 1944 the 35/ VIII Infantry regiment was intercepted by the Soviets and disarmed (TNA HS4-139). It had been rumoured 3 Divisions of Berling’s Army was marching towards Lwów (Lviv) which turned out to be false, however the commander of the AK was forced to sign a declaration of joining Berling’s Army with a revolver pressed to his head.

A substantial report (TNA HS4-140) describes the conditions in Poland between 11th January until 1st May 1945 of the newly ‘liberated’ Poland by the Soviets. The newly formed Lublin Committee acted as a puppet to the Soviets and NKVD who for all intents and purposes ran an annihilation programme in Poland to ensure the AK, independent, patriotic and intelligentsia which included landowners, noncommunist politicians and even Red Cross officials, would be neutralized from post war rebuilding of the Polish state. The Lublin Committee at this stage had no real powers and were deemed to be fiction for the Allies assessment of the newly formed government.

Mass arrests were made at night and usually disappeared without trace or summarily shot. Former Gestapo agents and collaborators were re-employed by the NKVD in many locations throughout the country, particularly in the Białystok/ Grodno area. The NKVD often wore Polish army uniforms while operating in the countryside and those local populous found with weapons or listening to radios were summarily executed. Those arrested were held in special concentration camps where prisoners were placed naked in pits in the ground after extensive torture. One technique employed, was to make prisoners stand for long periods with sharpened skewers close to their eyes where sleep or movement would impale them. The report also indicated 8,000 prisoners were held in the fortress at Lublin. The report concluded that on the disbandment of the AK on 19th January 1945, enabled the NKVD to hound out any survivors with somewhere in the region of 40,000 arrested as a result.

In April 1945 returning POWs from Germany were arrested for collaboration with the Germans with younger Poles being deported to Russia mainly to Kaluga as forced labour just like in Hungary or Czechoslovakia. The NKVD had increased its intensity to seek out any former members of the AK where in Siedlce 24 people were arrested and shot in the street while in Kraków a professor was also shot in the street. In Silesia the NKVD declared “German fascists do not exist here. They must have fled, and the German people do not constitute a menace to us. Pacifist Poles should be considered the most dangerous element and even Germans should be used to help wiping them out”. By 6th March 1945 bounties were being offered and any AK officers caught should be executed without trial. Such was the size of mass arrests that a new camp at Skrobów in the Lublin Voivodship was opened in April 1945.

The mass deportations re-started in January 1945 with 15,000 men, women and children sent east. In Lwów (Lviv) deportations started in the summer of 1944 and in January 1945 more than 4,000 people were arrested and sent to Luhansk labour camp in Russia followed by a further 5-6,000 of which about 60% were Poles and women made up about 20% of the contingent. Those sentenced to hard labour for 15 years were sent to camps in the Far East of Russia. The deportations from Lublin amounting to 15,000 people. As a result, members of the P.P.R were assassinated and locals to flee into the forests. Much of these events were corroborated in an interview with Miss Jane Walker who had served with the Polish Red Cross in Warsaw and had extensive knowledge and experiences within Soviet occupied Poland (TNA HS4-140). These reports from Poland were also corroborated in interviews with Lt. Jan Ciaś (courier), Lt. Wegierski (ex-POW), Lt. K Bieda (AK), Lt. W. Daszkowski (ex-POW) and K. Buszko that have extensive details confirming the extent of Soviet aggression and reign of terror (TNA HS4-140).

The Soviet army during early stages of the invasion of Poland in 1943-44 behaved well in many areas, however as other units entered Poland, rape, looting, stealing, and requisitioning anything the soldiers fancied occurred. For Zymierski’s Army (formerly Berling’s Army), they were not received well and had to use forced conscription to maintain numbers. They also persuaded lower ranks from the AK to join them, most likely under duress. Many fled to the woods that also hid renegade AK units. Link to Operation Vistula Berling was arrested after knowingly hiding former officers of the AK within his army to protect them with the 8th Infantry Regiment joining partisans in the forest in early January 1945 (TNA FO371-47709). Those more war hardened troops in Zymierski’s Army who had survived internment camps in Russia, had low allegiance to the Soviets and the dire shortage of trained officers impacted upon their effectiveness in action. The distrust also emanated from the slaughter of the Kosciuszko Division during an offensive in the central sector of the Eastern Front. The advancing troops indicated to the Germans they were coming over to give themselves up. The Soviet artillery shortened their barrage and only 600 men survived with a reserve battalion disarmed by the Soviets with many shot in the field of battle. There is no evidence of where the survivors were taken in the filed report (TNA HS4-138).

The scale of the horrors by both German and Soviet acts of genocide in Poland were not fully understood by the Allies and came as a shock to the Polish diaspora (Kornat, 2019) and later the Allies. Retribution by the Soviets was swift with the politburo. At the trials in Moscow of former Nazis, the ‘evidence’ did not include Katyń due to a mysterious ruling by the Politburo (Petrov, 2019) despite the findings by the Burdenko Commission.

Special legislation in the form of the Polish Presidents decree on 30th March 1943 sought to address the confluence of both political and jurisprudence that was to settle the concept of ‘war crime’ that had been defined under the Hague Conference in 1907 (Kornat, 2019). This was due to the Polish Penal Code being unequal in the definition and sanctions in the task of punishing German crimes despite strenuous efforts by the Government in Exile to acquaint world governments, the public and diplomats over the crimes committed (Kornat, 2019). While there were issues with the location, format and jurisprudence, an international commission was favoured by the Allies and not the Poles, hence the presidential decree.

The Russian stance remained that Katyń was not genocide, but a common crime and that under Russian law had expired (Komaniecka et al, 2013). This resulted in a deposition to the European Court of Human Rights between 2007 and 2010 since the Russians insisted the Polish officers had simply ‘went missing’. Complaints were handled in the European Court of Human Rights on 16th April 2012 which ruled it was a war crime and not expired with the continued stance by Russia that documents withheld through being classified, was inhumane and humiliating to survivor’s families (Komaniecka et alHello Julian

, 2013). The court challenged the effectiveness of the Russian investigation with the Grand Chamber judgement delivered on 21st October 2013. By a majority vote the court had no competence to examine the complaints against Russia under Article 2 (right to life) and Article 3 (prohibition of inhuman or degrading treatment) under the European Convention on Human Rights. Unanimously, the Grand Chamber concluded that Russia had failed to comply with its obligations under Article 38 (obligation to furnish necessary facilities for examination of the case) of the Convention. Some closure was beginning to take place.

Further Reading

Anders, W. (1949) “An Army in Exile: The story of the Second Polish Corps”, Macmillan & Co. UK.

Applebaum. A. (2003) “Gulag: A History”, Penguin Books, UK.

Davies, N. (2003) “Rising’ 44, The Battle for Warsaw”, Macmillan, UK.

Furr, G. (2013) “The “Official” Version of the Katyn Massacre Disproven? Discoveries at a German Mass Murder Site in Ukraine”, Socialism and Democracy, Vol.27, No.2, pp.96-129.

Gabriel, D. (2008) “Prosecution of Nazi and Communist crimes in Poland”, Crimes Committed by Totalitarian Regimes, editor Peter Jambrek ; translations The Secretariat-General of the Government of the Republic of Slovenia, Translation and Interpretation Division]. Ljubljana: Slovenian Presidency of the Council of the European Union, pp. 177-184.

Gleason, T.R. (2014) “Decade of Deceit: English-Language Press Coverage of the Katyn Massacre in the 1940s”, Presented to the History Division at the annual Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication Conference, USA.

Karski, K. (2013) “The Crime of Genocide Committed against the Poles by the USSR before and during World War II: An International Legal Study”, Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law, Vol.4, No.3, pp.704-758.

Kochanski, H. (2012) “The Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War”, Allan Lane, UK.

Komaniecka, M; Samonowska, K; Szpytma, M and Zechenter, A. (2013) “Katyn Massacre – Basic Facts “, The Person and the Challenges, Vol.3 No.2, pp. 65-92.

Kornat, M. (2019) “Lex Retro Agit: Polish Legislation on Nazi German War Criminals in the Concepts of the Polish Government-in-Exile in London (1942-1943), Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law, Vol.4, No.3, pp. 315-331.

Lukas, R.C. (1990) “The Forgotten Holocaust: The Poles under German Occupation 1939-1944”, Hippocrene Books, USA.

McGilvray, E. (2018) “Anders’ Army”, Pen & Sword Military, UK.

Mockaitis, T. (2022) “The Russian army has a long history of brutality — Ukraine is no exception”, The Hill (https://thehill.com/opinion/international/3264042-the-russian-army-has-a-long-history-of-brutality-ukraine-is-no-exception/) (Accessed: 10.09.2022)

Moorhouse, R. (2019) “First to Fight: The Polish War 1939”, The Bodley Head, UK

Paczkowski, A. (2003) “The Spring Will Be Ours: Poland and the Poles from Occupation to Freedom”, Pennsylvania State University, USA.

Paczkowski, A. (2019) “Crime, Treason and Greed: The German Wartime Occupation of Poland and Polish Post-War Retributive Justice” in “Political and Transitional Justice in Germany, Poland and the Soviet Union from the 1930s to the 1950s”, Brechtken, M; Bułhak, W and Zarusky, J (Eds), Wallstein Verlag/ Hubert & Co, Germany, pp.143-178.

Petrov, N. (2019) “Judicial and Extra-Judicial Punishment and Acts of Retribution against German Prisoners of War, 1941-1945” in “Political and Transitional Justice in Germany,

Poland and the Soviet Union from the 1930s to the 1950s”, Brechtken, M; Bułhak, W and Zarusky, J (Eds), Wallstein Verlag/ Hubert & Co, Germany, pp.265-296.

Prazmowska, A.J. (1995) “Britain and Poland 1939-1943: The Betrayed Ally”, Cambridge, Russian, Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies, Series No. 97.

Rees, L. (2009) “World War II Behind Closed Doors: Stalin, The Nazis and The West”, BBC Books, UK

Roberts, G. (2022) “Atrocities in Ukraine and the Katyn Analogy”, www.geoffreyroberts.net (Accessed 19.08.2022)

Rusin, B. (2013) “Lewis Namier, the Curzon Line, and the shaping of Poland’s eastern frontier after World War I”, Studia z Dziejów Rosji i Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej, XLVIII, pp. 5-23.

Thompson, E.M. (1990) “The Katyn Massacre and the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in the Soviet-Nazi Propaganda war”, in “World War 2 and the Soviet People”, Soviet and East European Studies Eds, Garrard, J and Garrard, C, St. Martins Press, UK.

Williamson, D.G. (2009) “Poland Betrayed: The Nazi-Soviet Invasions 1939”, Pen and Sword, UK.

Urban, T. (2020) “The Katyn Massacre 1940”, Pen & Sword Military, UK

Websites

The Katyn Massacre – Mechanisms of Genocide

The Katyn Massacre - Mechanisms of Genocide

Records Relating to the Katyn Forest Massacre at the National Archives

Polish History

The history of Katyn Massacre

Katyn Forest Massacre

The Katyn lie. Its rise and duration

THE SECRET SOVIET GENOCIDE OF WWII

Soviets admit to Katyn Massacre of World War

Notable Filmography:

Stalin and the Katyn Massacre (Les bourreaux de Staline - Katyn, 1940) (2020) Director: Cédric Tourbe.

The Last Witness (2018) Director: Piotr Szkopiak

Katyń (2007) Director: Andrej Wajda

Katyń Forest Massacre – documentary by TMARKE FUR BILDE

Katyń Forest Massacre – documentary by TMARKE FUR BILDE

Selected youtube.com resources:

Mark Felton Productions – Katyń – WWII’s Forgotten Massacre (2021)

Military History - Katyn Massacre | the WAR CRIME that the USSR tried to hide in WWII

Disturban History - The Katyn Massacre - Short History Documentary (2020)

Russian History Documentaries – Katyń massacre, a truth revealed (2018)

|