Polish Counter-Intelligence Operations

Introduction:

Polish Intelligence networks were global and in part the envy of the Allies. It grew from 4 stations and 30 personnel with 30 agents to a network spanning 8 stations, 2 independent intelligence stations with 33 cells and employed over 1,666 agents (Kochanski, 2012). While CONTINENTAL ACTION (Akcja Kontynentalna) provided both military, economic, political, and diplomatic intelligence, counterintelligence was crucial to the survival of the AK and the Government-in-Exile.

Counterintelligence was part of the Ministry of National Defence (MON). The department of Offensive Counterintelligence was run under the auspices of Capt. Rudolf Plocek with a small, dedicated team collecting and analysing data from individuals or organisations that posed a threat (Pepłoński and Suchcitz (2005) and reported to Lt. Col. Miniewski. Returning agents were de-briefed and results of operations shared with the Allied intelligence agencies under the British-Polish Agreement of August 1940 (Peszke, 2011). The department (CID) was broken down into sections: General, Counterintelligence, Security and Anti-subversives. Consular officials cooperated with Polish military intelligence through consular officials performed specific duties besides their role within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs working with ‘residents’ who were full-time intelligence officers (Skóra, 2004). The main thrust of the counterintelligence was through monitoring known individuals or organisations with the Polish diaspora providing a wealth of local information (Skóra, 2004). Military Attachés were not directly involved in spying activities but gave direction to intelligence officers and couriers working within the diplomatic services. Legations in various locations like Budapest also provided some diplomatic and intelligence services that included assistance in providing forged documents for escapees and evaders until their closure as the war spread across Europe.

Poland’s counterintelligence had experimented with narcoanalysis in the 1930s through the work of Capt. Ludwik Krzewiński who developed the drugs and techniques used during interrogation (Widacki, 2022). His medical career included research and lecturing on the early development of chemical weapons and managed to escape to France with Lt. Col. Gano and served with the 1st Grenadier Division before arriving in Britain. Much of Krzewiński’s life and work remains clouded in mystery with inconsistencies in detail clouding the story (Widacki, 2021).

The screening of evacuees from occupied countries formed a key role within the department, particularly from the Soviet Gulags where many soldiers and civilians had been under NKVD control where extorsion and threats to surviving family still held within the system proved effective. Communist activity by sympathisers was also passed on to British Intelligence (SIS) to ensure security levels in Britain were maintained and ‘Action D’, the misinformation/ black propaganda department used its skills and opportunities to de-stabilise the Axis.

Re-emergence of the Polish State and Interwar Years:

Between 1918 and 1939 Polish counterintelligence was formed to protect the country, its military and defence industry plus disputed borderlands (Kimmich, 1969). During the interwar years counterintelligence was based around Poland’s foreign policy and behaviour of its near neighbours with the rise of the Nazi’s and Soviet aggression towards the newly emerged state. Polish diplomatic centres that collected intelligence were principally covered by Berlin, Moscow, Tokyo, Paris, and Prague.

The military restrictions imposed on the Weimar Republic by the Treaty of Versailles also included offensive intelligence activities (Napora, 2016) that were circumvented through use of underground organisations and private intelligence gathering firms working on behalf of the Abwehr with some acting independently for more commercial or political reasons as the prospect of the Third Reich emerged. The Polish intelligence services estimated approximately 200 assassinations between 1919 and 1923 were carried out by the Abwehr (Napora, 2016). The private organisations of the Stahlhelm (after 1924 became Reichswehrministerium) and Banschuts operated within Greater Poland, Pomerania and Upper Silesia collecting intelligence and keeping track of former German military personnel, German minorities and reported to the Abwehr as ‘detective agencies’ in effect paid locums to circumvent the treaty’s conditions. The Abwehr also used many companies to support or act as ‘fronts’ (Napora, 2016) to their activities that included:

- Wirtschaftsinstitut Für Russland und die Oststaaten

- Max Bange Import Export

- Barasch et Companie

- WJaeger, Rothe et Companie; Chemische Fabrik

- Landeschaum für die Previas Oberschlesien

- Kartell der Auskunfteien Burgel

- Ost Berichte für Industrie und Landwirtschaft

- Schiffarte-Gesallschaft

- Stinnes AEG Export-Import

- Siemens

- Singer

Linked to these operations was a quasi-trade body Deutscher Wirtschaftdienst (D.U.D) that had five departments covering a wide range of intelligence and commercial data gathering and analysis. After 1927, some restrictions of the Treaty of Versailles were eased when international supervision ceased enabling covert operations to resume.

German intelligence increased its activities towards Poland with sabotage units active in Silesia, Wielkopolska and Malopolska by the Wrocław Abwehra (Chinciński, 2005) prior to the invasion and partition of Poland. Nazi propaganda continued to portray Poland as an aggressor towards the Volksdeutschen prior to the outbreak of war (Bergen, 2008; Vitti, 2014; Siewier, 2020) as part of its justification to invade. However, Polish counterintelligence services had operatives in place. For example, Paulina Tyszewska was married to the deputy head of the Abwehr post in Gdańsk, or Lt. Reinhold Kohz or Wiktor Katlewski, a Polish national working at the German Naval Weapons Department (Marinewaffenamt) in Berlin (Skóra, 2019a) all of whose patriotism cost them their lives. During this period, counterintelligence officers operated in the free-port of Gdańsk (known as PO-2). Counterintelligence used the visa offices as a cover for its operations in its global network (Skóra, 2004). The port of Gdańsk was a haven for smugglers, forgers, common criminals, refugees, and spies with intelligence officers monitoring German activities and their network of contacts (Skóra, 2019a).

A police commissioner from Toruń, an agent Kokino (probably Adam Wysocki), was sent to Gdańsk to assist local police. As a drug addict, Kokino was blackmailed by the local Abwehr to become an agent due to his contacts with the authorities, police, and intelligence services. Unmasked, Kokino provided Polish counterintelligence with an opportunity to fabricate information that covered both real German agents and some innocent people were intended to be arrested for activities against the state. The local Abwehr realised they had been duped and Kokino met an untimely death through a road traffic accident (Anon, 2012).

Between 1925 and 1926 Lt. Heinrich Rauch of the Królewiec Abwehr recruited a Pole, Lt. Paweł Piontek through debt entrapment to spy for Germany covering Pomerania (Anon, 2012). He was tasked to set up a spy network with the focus set on obtaining documents from DOK VIII (Dowództwo Okręgu Korpusu) in Toruń. The use of relatives, an unstable lifestyle and blatant refusal to follow the ‘rules’ of conspiracy brought him to the attention of Polish counterintelligence. They used Polish informants and false documents given to Piontek knowing these would be handed over to the Abwehr. Piontek was trusted by the Abwehr, and Polish counterintelligence succeeded in turning him into a double agent for a brief period before the entire spy network was broken up with Piontek and an officer Urbaniak sentenced to death and shot by the Poles.

These were not isolated cases. Leon Adamczyk was recruited in 1925 by the Abwehr and acted as a valuable source for them providing details of Poland’s military expansion and investment during the inter-war period that also included the mobilisation plans set up in 1933-34 (Anon, 2012). On his transfer to the Korpus Ochrony Progranicza (K.O.P - border guards) Adamczyk provided information relating to the borderlands and defences, and successfully managed to escape detection throughout the war. He was eventually caught and shot in the aftermath of the war.

The head of the Polish intelligence in Berlin, Józef Gryf-Czajkowski was either ‘turned’ by the Abwehr or volunteered his services to them between 1923 and 1926. He fed false intelligence reports to Polish II Bureau on the state of the Weimar’s rearmaments programme. He also betrayed a deep cover Polish intelligence officer Capt. Jerzy Sosnowski (Georg von Nałęcz-Sosnowski, Ritter von Nalecz) to the Germans. Fortunately, the quality of Gryf-Czajkowski’s information was so poor that Polish counterintelligence was alerted. He was caught after shipping documents to Gdańsk and interrogated. He denied exposing Sosnowski. In January 1934, the District Court in Toruń sentenced him to death and shot on 2nd February 1934. Capt. Jerzy Sosnowski’s adventures and activities in Berlin became legendary and subjected to scrutiny over the level of his successes and his complicated private life with his female spies in the Reichswehr. On his exposure by Gryf-Czajkowski, the Gestapo arrested Sosnowski on 27th February 1934 and sentenced to life imprisonment while his accomplices were tried and beheaded. Sosnowski would later be part of a spy exchange in April 1936 and tried for high treason. Although he denied all charges, he was found guilty and sentenced to fifteen years in prison. On the outbreak of war, Sosnowski was either shot by prison guards at Brzesc or Jaremcze on 16th or 17th September just as the country was about to be partitioned. Alternative stories indicate he was captured by the NKVD during the partition of Poland and transported to the Lubyanka Prison in Moscow. He was later reported to have joined the NKVD and lectured in their espionage school in Saratov (where he also was reported to have died after a hunger strike for not being released under the Sikorski-Maysky Agreement). In September 1944, it is alleged he was in Warsaw during the ‘Rising with the Soviet backed People’s Army (Link: Warsaw Rising) where he was possibly killed or executed by the AK. Whatever his fate, mystery still surrounds him to this day.

Recent research has unearthed evidence of cooperation between the Reich and Soviets between 1921 to 1926 (Landmann and Bastkowski, 2017). II Bureau had become aware of close cooperation between the Reich and Soviets where combined intelligence gathering of political, economic, and military developments were used to underline the notion that the Soviets would not counterattack the Germans in Poland after the German invasion in 1939. After 1926 the relationship cooled due to friction between the two states caused by the Junkers-Werke factory in Fili near Moscow ceasing production of aircraft and the abandonment of agricultural licenses and credit support due to crop failures in the Soviet Union. Yet, on the night of 23rd to 24th August 1939, Germany and the Soviets signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of non-aggression despite these differences which had a time limit of ten years and their goal for further territorial gains in central Europe and economic cooperation was clearly stated. The Soviets had also penetrated Poland’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Świerczek, 2019). And like the Germans, the Soviets were not interested in the violation of International Law and exploited international political myopia that existed at that time, particularly the ‘Big Four’. The fate of Poland appeared to be sealed. However, Polish counterintelligence had an ‘ace up its sleeve’.

Polish Customs in Warsaw inspected a package mis-directed to Poland that prompted an immediate diplomatic protest from Germany that the package should be returned immediately and un-opened. With their suspicions aroused, Polish Intelligence technicians checked out the contents and found a commercial version of the Enigma machine. Quite calmly and with a dash of audacity, Biuro Szyfrow ordered an Enigma machine from the manufacturers in Germany by using a false cover and address. Initially Biuro Szyfrow had great difficulty in breaking captured radio traffic and in January 1929 approached the renowned mathematics institute of the University of Poznan (Budiansky, 2000; Ciechanowski and Tebinka, 2005). In 1937, the structure and function of the Enigma machine had been upgraded to include six different sets of keys, rotors and connecting plugs. In response, Rózycki constructed a ‘clock’ to Rejewski’s use of a ‘cyclometer’ thus enabling cipher traffic to be read (Budiansky, 2000; Ciechanowski and Tebinka, 2005). Through the interception an SD code used by the Wehrmacht enabled the 4th and 5th rota settings to be utilised in the code breaking.

To the reluctance of the British, the newly formed Enigma team that also included French and Polish cryptologic services, met in Paris on 9-10th January 1939. Capt. Gustave Bertrand took strong steps to persuade Alister G. Denniston (Head of Britain’s code and cypher school) to attend a meeting at the Pyry on 25th July 1939 and shown the replicas of the Enigma. Just before the outbreak of war, the Poles had by 6th July read German coded messages. On 6th September, the Polish team escaped eastwards towards Brześć and through into Romania just after the Soviet invasion with Rózycki, Rejewski and Zygalski eventually arriving in Britain after a short working stay in France (Link: Enigma).

**********

Soviet intelligence had also conducted aggressive operations in support of actions on the eastern border (Kresy) that undermined the financing and resourcing of operations against the Germans (Machniak, 2017). The Soviets had communist cells within Poland that were uncovered prior to the partition by the Germans and Soviets. After the Soviet defeat at the gates of Warsaw in January 1920, the Soviet leadership redacted the significant failure of the Red Army’s leadership that enabled the new European order after the Treaty of Versailles to be temporarily maintained (Korkuć, 2019), but under pressure due to various land grabs by Poland, Hungary and the Czech’s. Despite these minor border infringements in central and eastern Europe, the post Great War Treaty of Versailles remained functioning September 1939.

The Soviet started to undermine the Treaty of Riga by passing a resolution at the Cominton’s 5th Congress for East Galicia to be incorporated into the Soviet Union (Rogalski, 2017). The regional Commissar, Josef Stalin tried to cover his failings in the 1920 Soviet defeat through using Lord Curzon’s proposals as a cover for political manipulation within the region (Rees, 2009). After 1921 specially trained groups of Ukrainian and Belorussian Bolsheviks and Red Army soldiers slipped over the Polish-Soviet border to attack local police stations and local administrators, causing damage until the formation of the KOP in 1924 that began to restrict activities and incursions (Komaniecka, et al, 2013; Ochał, 2018). Piłsudski’s land grab and Polonization infuriated the local non ethnic Polish populous (Rogalski, 2017) with new landlords taking the more fertile land, lucrative government posts and business opportunities. Galicia had been the boundary between the old Tzarist Russia and the collapsed Austro-Hungarian border that enabled Polish claims to have some legitimacy in Piłsudski’s land grab (Eberhardt, 2012). Indeed, during the Great Terror of 1937-38 in the Soviet Union, many foreign nationals were falsely accused of being spies for foreign states (Morris, 2004) and this was used effectively during the partition by the NKVD under operational order No. 00485 issued by Nikolai Yezhof as the People’s Commissar for Internal Affairs (also known as the Polish Operation) on 11th August 1937.

The Soviets were active in recruitment of Polish agents during the early days of the 2nd Republic’s formation (Świerczek, 2019) and after the partition Poles sent to the Gulags were deemed to be a suitable source for recruitment. Research by Kuromiya (2021) suggests Soviet disinformation in the 1930s collected by a Polish intelligence officer, Jerzy Niezbrzycki, and other experienced foreign intelligence operatives in Russia, were successfully misled with the evidence buried in archives for many years. It is also known that Ursula Kuczynski (Ruth Werner) was dispatched to Gdańsk in 1939 to advise German communists after the Germans seized the port in the September campaign before retracing her steps to Warsaw and then Moscow.

Meanwhile, the local populous remained indifferent to the partition and resisted the demarcation lines (Bodridczenko, 2022) by continuing their daily lives crossing the border frequently irrespective of the current sovereignty. Post-war, those AK officers based in eastern Poland, if they had survived the war, were brutally repressed by the NKVD (Kochankski, 2012; Korcuć, 2019).

Polish counterintelligence was alerted to a potential threat from Georgian ‘social democrats’ who had ended up in Poland’s officer class after the Great War (Adamczewski, 2019). Lt. Stanisław Zaćwilichowski while posted to Paris in June 1929 met Noe Ramishvili who during a discussion, indicated plans were in place to remove Polish officers opposed to Georgian officers in the Polish army. Zaćwilichowski reported the conversation to senior officers that the move was political rather than potential collaboration with foreign intelligence services, particularly the Germans. Ramishvili was the first Prime Minister of Georgia and was assassinated in the streets of Paris in 1930 on the orders of Beria to secure Stalin’s regime (Adamczewski, 2019). Some members of the Polish Military Organisation (Polska Organizacja Wojskowa), a secret right wing nationalist party used by Piłsudski to undermine Russian and Austro-Hungarian interests in the then divided Poland (in parts of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Belarus and the Ukraine), posed a threat to the Soviet intentions for Poland and its eastern borderlands whose activities needed to be curbed with some officers dismissed from the Polish armed services.

**********

Despite Switzerland’s neutrality, Swiss counterintelligence unearthed a Soviet cell known as the Red Three. Switzerland like neutral Portugal, was an important spying ‘hub’ for both the Allies and Germany. The Soviets had no diplomatic legation in Switzerland and so the ‘cell’ worked in the shadows with limited support from Moscow. The main operation was based in a chalet in Caux above Montreux (Heim, 2022) whose local hotels housed both German and Allied POWs or Red Cross medical evacuees, many of whom were mainly ‘downed’ aircrew or evaders. Ursula Maria Kuczynski (Sonia) operated under the name of Ursula Schultz to recruit and despatch agents into Germany. From 1940 they operated a powerful shortwave transmitter with the assistance of an Englishman, Alexander Foote (Jim) who had fought in the Spanish civil war. From 1938, the Soviets had in place a Hungarian cartographer, Sándor Radó (Dora) and Rachel Dübendorfer (Cissy). Another cell included a Swiss journalist Otto Pünter (Heim, 2022). They set up a triangle of powerful shortwave transmitters in Lausanne (operated by Foote) and two in Geneva who were operated by Edmond and Olga Hamel (Eduard and Maud). Intelligence was also collected by Rudolf Rössler (Lucy), a German émigré living in Lucerne who had overall command of the Swiss operation. The transmissions had been intercepted by the Swiss and the Allies counterintelligence ‘listening’ stations. The Poles were interested in the closure of these cells due to the high number of interned Poles from the 2DSP in Switzerland (about 11,000) and their own operations within the country (Link: Polish Army/ The Polish Army in France & 2DSP Internment in Switzerland)). By early October 1943, the Swiss authorities had pinpointed the locations so that by November 1943 the cells were broken (Heim, 2022). Most of the group were tried in absentia with Foote, Radó and Dübendorfer fleeing and eventually arrived in the Soviet Union for interrogation and imprisonment until the 1950s. Foote escaped detention and worked for the NKVD. In contrast, the Lucy Ring that was an anti-Nazi operation was run by Rudolf Rössler under the direction of Brig. Masson, head of Swiss Intelligence who had managed to provide a radio and an Enigma machine. Rössler had been approached by two German officers, Fritz Thiele and Rudolf von Gersdorff who were conspirators to overthrow Hitler. Classified information was passed to Rössler via his news clipping service Bureau Ha as a cut-out to distance him from Swiss intelligence. German counterintelligence became aware of the Lucy Ring and persuaded the Swiss to close-down the operation in October 1943 after it had passed on the details of operation CITADEL on the Eastern Front (Mulligan, 1987). Rössler continued with the operation until the summer of 1944 when co-conspirators in Germany were arrested after the failure of the July plot to assassinate Hitler.

Neutral Switzerland acted as a conduit for intelligence traffic between the anti-Nazi head of the German Abwehr, Admiral Canaris and high-ranking officers in the German high command (Winter, 2011). For some time, it has been assumed the breaking of the greatest secrets of the Third Reich was based on signals intelligence (SIGINT) through the decryption of traffic through Enigma code breaking at Bletchley (Budiansky, 2000; Davies, 2001) rather than human intelligence (HUMINT). Winter (2011) suggested the use of at least two high-level agents within the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht and Oberkommando des Heeres, ‘Warlock’ and ‘Knopf’ played a significant role in the access to German strategic and operational planning too. Warlock was caught and turned in 1940-41. Knopf provided vital information during the period 1942-43 but was compromised in the summer of 1943 through decoded communications of the Polish military attaché in Switzerland (Link: Polish Army/ The Polish Army in France & 2DSP Internment in Switzerland)).

**********

While the thought of Polish treachery was an affront to the newly emerging Polish state, it must also be remembered that as a divided nation between Germany, Russia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, many former military men had sworn an allegiance to those countries and had fought for them during the Great War. These men were of interest to foreign intelligence agencies for potential collaboration who played upon their former loyalty and exerted pressure through potential threats to their families. Many senior officers, particularly in the Austro-Hungarian army conspired for the re-emergence of Poland as an independent state for many decades. Many of these officers became the ‘backbone’ to the political and military institutions in Poland during the interwar period which in part explains the rapid rebirth of the nation.

Polish Underground State and Counterintelligence:

What distinguished Poland from other occupied countries by the Axis, was that the civilian state in terms of administration, education and judiciary continued to function with the military or Home Army (Armia Krajowa) providing resistance to the Reich (Kochankski, 2012; Korcuć, 2019). Although the Nazi’s attempts to close religious, cultural and educational institutions while at the same time stealing businesses and deporting sections of the populous as slave labourers, Poland struggled on facing extreme danger and repression in all quarters of life. Even during the partition of Poland, the NKVD failed to break the structure and spirit of the country while overseeing the deportation to the Gulags of civilians and POWs.

Occupation was a ‘rich’ recruiting ground for agents in both Poland and other European Countries that helped Akcja Kontynentalna to become one of the most effective networks supporting the Allies. Other independent groups developed resistance networks, often working independently of each other (although many were affiliated to political parties), the AK and the Government-in-exile. One of the first groups to provide information and reports on the German occupation came from the ‘Muszkieterowie’ or Musketeers whose networks covered 32 towns in occupied Poland and by 1941 stretched into the Reich, Soviet Union, Hungary, and the Balkans (Pepłoński, 2005a). (Link: Home Army & SOE/ The Musketeers, Intrigue, and the Balkan Connection))

The Nazi propaganda machine had a ‘hollow propaganda triumph’. After the invasion in 1939 Einsatzgruppen units, military police, counter-partisan units, and the Security Service (SD) were active throughout Poland under operation UNTERNEHMEN TANNENBERG which included the extermination or shipment to labour camps of the intelligentsia including those who participated in pre-war uprisings in Silesia and Wielkopolska (Siewier, 2020). The notorious SONDERAKTION KRAKAU which resulted in the arrest of 183 academics mainly from Jagiellonian University, but also from AGH University of Science and Technology, the Business Academy, the Catholic University of Lublin, and the Stefan Batory University. Transported to Sachsenhausen concentration camp (Paczkowski, 2003; Kochankski, 2012; Komaniecka, et al, 2013) few survived. These actions were not overlooked by the AK and counterintelligence services where under Operacja Główki assassinations were sanctioned by underground tribunals.

In the field, counterintelligence formed a crucial role between the regional sub-stations and specialist cells focussing on specific problems. For example, Station F for France with ‘300’ and Interallié (INT) ran separate operations with the counterintelligence cell of Maj. Kazimierz Kwienciński running couriers between Vichy and the occupied zone where links to key French Vichy politicians were maintained throughout the war.

However, the networks were subject to the activities of the Abwehr, the Milice, the Gestapo and exposed to individual treachery. In the case of Interallié (INT) it was established in Paris in July 1940 and covered the occupied zone with a cell operating in Belgium whose duties were to cover all the activities of the German occupiers. The network which included an escape line was set up by Wincenty Zarembski (Tudor), Mieczysław Słowikowski (Ptak and later Rygor) and Roman Czerniawski (Armand, Valentin) who were later joined by Tadeusz Jekiel from II Bureau in London to help consolidate the network. Their main locations were Lyon, Marseilles, Bordeaux, and Toulouse in Vichy France using couriers employed by Wagon-Lits (Bennett, 2005). They also set up through Bordeaux cell ‘Italie’ reporting on troop movements by the Axis into Italy and the Mediterranean.

In November 1941 the network was exposed and destroyed (Bennett, 2005). Interallié had been penetrated by the Gestapo with hundreds arrested and some ‘turned’. Wincenty Zarembski (Tudor), Capt. Roman Czerniawski (Armand) and Mathilde Carré (La Chatte, Bagheera) were arrested with 100 agents and five radio stations closed. Roman Czerniawski and Mathilde Carré were accused of collaboration with Carré being ‘turned’ by the Gestapo. Roman Czerniawski went on to be a double agent (Brutus) and was responsible for tricking the Germans to withdraw key units from Normandy in favour of Pas de Calais. Wincenty Zarembski managed to escape to London before the double-cross was exposed. Mathilde Carré escaped from France with resistance leader Pierre de Vomécourt and on arrival in Britain she was arrested and imprisoned for treachery due to her contacts with the Vichy and suspicion of being a double agent for the Abwehr. Although sentenced to death in January 1949, it was commuted to life imprisonment and released in September 1954. She became regarded as the most dangerous agent operating in France.

At the outbreak of war Wincenty Jordan-Rozwadowski (Pascal) was acting as Aide-de-camp to Gen. Juliusz Kleeberg in the Vichy. He acted as a link to various political circles as a liaison officer to the resistance. He also worked closely with the maritime network of Polish intelligence in France (Marine, P-O4 and later Agency F). After the cell in Nice was destroyed, Rozwadowski went to Switzerland and negotiated with the Swiss intelligence a counterintelligence agreement not to interfere with Polish operations between France and Switzerland. This agreement enabled F2 to be created in France under the auspices of II Bureau in London with numerus success stories including the maps of German defences and logistics crucial to D-Day planning. The Gestapo arrested many collaborators of F2 who were made up of largely French citizens, however security processes that were in place saved Rozwadowski, having been arrested twice. Eventually, he set up cells in the northeast of France.

By 1943 the Funkabwehr were successful in listening to Polish radio traffic and had successfully decoded much of the traffic (Triantafyllopoulos, 2020) between France, Switzerland, and Portugal and had a clearer understanding to the degree of intelligence gathered on key defences, manufacturing, and logistical support for the German army. ‘FII’ as it was known (headed by Maj. Zdzisław Piątkiewicz, Lubicz) was a vast network across France employing 1,500 agents and couriers divided into smaller regional cells. Its centre was in the remote farms in the Grenoble-Chambéry area and due to a duplication in the structure, was more secure from counter-intelligence operations (Wnuk, 2005).

**********

It is difficult to gauge the effectiveness of counterintelligence operations due to restrictions on archived material, however enemy agents and traitors were successfully exposed and captured. In the case of Dr. Stefan Stary-Kon Kasbrzycki (Janusz) (TNA/ HS4/ 274) was found guilty of being a Gestapo agent in Wrocław. As a reserve officer he acted as an intelligence officer for Z.W.Z (Związek Walki Zbrojnej). After the fall and occupation of Poland, he was sent as an emissary for the AK to Germany and then became a courier to London. He revealed to theGestapo his orders, codes, and functions within the AK along with his contacts inside Germany and documents bound for London that had been intercepted and read. He had been arrested in 1940 and sent to Auschwitz that at the time housed many former Polish officers before conversion to a labour camp. He was later transferred to Groß-Rosen to the west of Wrocław. In the spring of 1943, he was liberated and arrived in Warsaw with a cover story that the Tyszkiewicz family who had close links to the Italian Royal family, had assisted in his release (TNA/ HS4/ 274). He now claimed to be a German of Polish descent. He managed to persuade the AK to allow him to work for the I.K.O (Inspectorate of Organisational Cells), an organisation dealing with Polish workers deported to Germany as slave labourers. He betrayed the following who were all executed:

- Irena Prochnik (Eliziberta) who organized workers in the Reich.

- Kamila Remiszewska in Warsaw

- Ludwik Renk in Berlin

- Jan Lachowski in Szczecin

- Marian Keller in Oebisfelde near Wolfsburg and sent to a concentration camp.

- Zofia Remiszewska

His contacts were Mikolaj and Kasbrzycki’s wife who lived in Warsaw under the guise of Paszkowska who was also implicated in the treason. At the same time Alexander Feld, the brother-in-law of Richard Maczynski, was in continuous contact with Hauptmann Gallen and Hauptsturmführer Burkner in the Gestapo. Maczynski and Feld planned to escape to Lisbon where they were detained and interrogated by the Poles. By special Court Marshall, Kasbrzycki was sentenced to death under military codes of conduct on 15th December 1943.

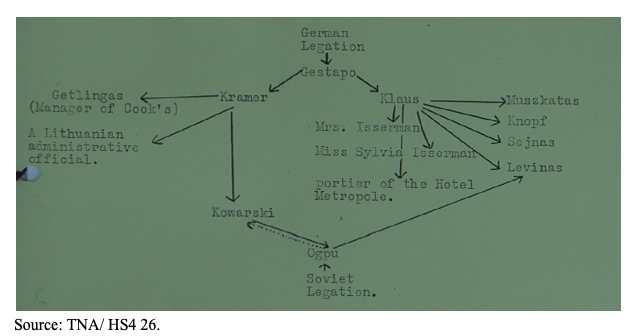

The Gestapo had their own networks employing local inhabitants who were recruited either through duress or were sympathetic to the Nazi dogma. In Lithuania, in the city of Kaunas (Kovno) the Gestapo established a small network of informers and spies. They recruited Kowarski by the Gestapo chief, Kramer under the orders of Col. Lissa through the German Legation in the city in May 1940 (TNA/ HS4 – 261). His role was to recruit agents for theGestapo and the OGPU (the Soviet State Political Directive) that reinforces the degree of cooperation between the Soviets and Germany prior to Operation BARBAROSSA (Landmann and Bastkowski, 2017). The pictogram below describes the structure and relationships.

Recruitment of agents and those seeking collaboration with the intelligence services took many forms. Through the Polish Legation in Lisbon, the Consular services provided an ideal opportunity to screen passports from those seeking transit or exit visas. It helped alert the authorities to 5th Columnists, Nazi spies, and provided a recruitment opportunity. One such case was Franciszek Moskal (Teodar Martyniuk), a courier for SOE Polish Section and was issued a diplomatic passport for operations in the Soviet Union as an ‘attaché’ to the Polish embassy in Moscow. On 24th July 1942 a passenger, Eugeniusz Mazurek aboard a ship entering Bermuda claimed he was a British agent for SIS (number 37). On checking, there was no trace of him working for SIS or SOE. II Bureau would interrogate him on his story (TNA/ HS4-261) and exposed as a fraud seeking entrance to the USA. Likewise, a Mrs. Miladowska on arriving in Portugal sought an exit or transit visa that raised concerns as it was rumoured she was a German agent (TNA/ HS4-261) who might be infiltrating another country.

Lisbon, the great spy hub of Europe played a central role in intelligence gathering and the Poles used the legation to screen individuals. For a short period of time, Col. Ignacy Matuszewski (TNA/ HS4-261) was in Lisbon in June 1941. Prof. Kot had tasked him with setting up an organization in Vichy Morocco on similar lines to ANGELICA (Link: Home Army & SOE/ Operation Monika)). Matuszewski was a career soldier who fought for the Russians in the Great War. He was also an intelligence officer, a banker who held the post of Finance Minister and diplomat who had escaped Poland after arranging with Henryk Floyar-Rajchman the evacuation of Poland’s gold reserves (75 tons) through Romania, Turkey, and Syria to France. His own escape was through Hungary via Italy to France and resided in Nice before heading to Spain where he was arrested despite his diplomatic status (TNA/ HS4-261). Temporarily imprisoned in Madrid, he was released after pressure from the British Ambassador Sir Samuel Hoare and then made his way to Lisbon where his family were due to leave for Canada. He was not in favour of Gen. Sikorski’s policy towards the Soviets, and it appears to have turned down Kot’s offer of subversive work in Morocco since in September 1941 he entered the U.S.A. The north African project evolved into Agencja Afryka run by Maj. Mieczysław Słowikowski (Rygor) as a major espionage coup for II Bureau. Serviced by feluccas out of Gibraltar, it was an extensive network that covered the whole of north Africa and played a central role in intelligence gathering for Operation TORCH in November 1942 (Ciechanowski, 2005). The agency also included counterintelligence activities against the Vichy Government (Link: Feluccas & the SOE)).

Initially, the remnants of the Polish army were secretly evacuated from Vichy France with some 2,500 travelling to north Africa between July 1940 and May 1941 with a further 4,500 to 5,000 escaping by 1944 (Bielak, 2019). On arrival at their ‘depot’ and prior to entering a military training programme, counterintelligence would have interviewed the new arrivals for 5th columnists or potential Nazi agents. The interrogation would include the need for personal references from senior officers who could vouch for them and since many were veterans of the Polish Army in France, the process was not too gruelling if documents and verification were in place.

**********

‘Black propaganda’ has formed part of counterintelligence operations to discredit the enemy through disinformation that is deniable by its source. The AK during World War II became masters of this technique through Operation N (Akcja N) with the department led by Tadeusz Żenczykowski (Kania, Kowalik and Zawadzki). Żenczykowski, a war veteran and former politician who worked for the Bureau of Information and Propaganda of the AK and later from 1943 headed the Akcja Antyk, an anti-Soviet and communist campaign. These activities were to counter the German propaganda which was attempting to erase the Polish and Jewish culture with the replacement by Volksdeutschen to legitimise Nazi atrocities and forced migration or enslavement (Bergen, 2008). The Polish state had experimented with black propaganda in the 1930s (Simic, 2010) to counter Nazi and Soviet threats (Salata, 2020) and this experience became invaluable to Operation N. Although the state Radio Polskie continued to broadcast throughout the war, it only acted a ‘voice’ for the Nazis and banned by them to the local Polish population .

Operation N was a psychological campaign against the Germans producing newspaper and leaflets purporting to be issued by German anti-Nazis. These activities included false orders for the German civilian population in all areas of Poland, particularly Warsaw that sowed chaos. Such was the quality of the content, the Abwehr and Gestapo believed the level of dissent within Germany and the military truly existed (Nowak, 1983). Sub-Department N consisted of five sections:

- Organisations

- Studies

- Subversive actions

- Editing

- Distribution of publications

Printed in secret locations around 750-900 people distributed pamphlets of religious and satirical content. It ranged from communist to monarchist in all forms of political persuasions. Many were distributed to German troops heading to or returning from the Eastern Front on troops trains (Nowak, 1983) to undermine the morale of the troops or into the Reich and Volkesdeutsche communities transplanted into occupied Poland. The titles included:

Der Soldat, Der Frontkämpfer, Der Hammer, Der Durchbruch, Der Klabautermann, Die Ostwache, Die Zukunft and Kennst Du die Wahrheit. Each was tailored to a targeted audience, for example, Die Zukunft was aimed at destabilizing the Volkesdeutsche while other publications were themed around anti-Nazi conspiracy organisations to weaken the morale of German troops into thinking the war was lost (TNA/HS4-170). The anti-Nazi organizations included:

Heimatsbund ‘Freiheit und Frieden, Süddeutscher Freiheitsbund, Der Verband Deutscher Frontsoldaten and Der Deutsche Demokratenbund.

To compliment these actions, radio stations also played a leading part. The BBC Polish section regularly broadcast bulletins (Nowak, 1983). Radio Swit was encouraged by SOE’s Polish section (E/UP) to broadcast bulletins on sabotage operations as long as no one was endangered (TNA/ HS4-167). Swit (Dawn) broadcasted on 31 metre band between 8am to 7pm via a powerful transmitter purportedly in Europe whereas in fact it was in Britain, a ship off the coast of East Anglia (Davies, 2003). To provide a degree of authenticity, the AK would provide ‘local’ news and events to enrage the Germans. Radio Wawa (slang for Warsaw) was based at Fawley Court near Henley and used coded messages within open messages to communicate to various groups in the underground army (Davies, 2003) and were different in approach to the messages sent to the French partisans, for example.

The BBC’s Polish section began broadcasting on 7th September 1939 and started bulletins with “Tu mówi Londyn” by Józef Opieński (Bretan, 2022). A small team of journalists worked closely with the government-in-exile and SOE to broadcast on Wednesdays and Saturdays at 20.30 and provided a vital link to the Allies and more importantly the government-in-exile (Moriss, 2015). Despite time limited broadcasts, it became a symbol of resistance even though listening to the BBC or radio Swit and Wawa was punishable by death (Davies, 2003).

As part of the disinformation campaign operation MARTINI was to broadcast ‘news’ into Germany. The eastern zone was covered by the AK and the western zone would be covered by Wojskowa Organizacja Propagandy Dywersyjnej which was attached to VI Bureau, with centres in France and Switzerland (TNA/ HS4-170) with the material being agreed on by SOE and the Polish General Staff based in the Rubens Hotel in London and in consultation with Britain’s P.W.E. Diversionary propaganda was also broadcasted from Turkey into central Europe and the Balkans with the similar content to destabilise the German troops in the occupied countries.

The use of newspapers in the USA (over 100 Polish language publications) aimed at the diaspora were also used to alter America’s views on the European turmoil (TNA/ HS4-170) with leaflets dropped in containers for Cichociemni operations such as operation JACKET (TNA/ HS4-170) for the local population. The first leaflet drop was planned for operation RUCTION in November 1941 despite Jan Librach’s request to drop bombs, not leaflets that was in the end ignored by SOE. Soviet transmissions were also monitored by both the Poles and British (Military Section: Russian) and the War Office (Russian Section) with MI8 and GC&CS being passed information for analysis (Maresch, 2005).

Whilst psychological warfare through black propaganda had a measurable effect on the German occupiers, the Polish Underground State maintained its judicial system. For those who collaborated and those occupiers whose brutality could not be overlooked would be punished. Death squads and assassins played an important part in destabilizing the Nazi regime in Poland under Operacja Główki. Gauleiter Franz Bürckel, the Governor of Pawiak Prison in Warsaw was assassinated on 7th September 1943 after an underground court sentenced him to death due to his brutality towards the Jews, Polish civilians, and prisoners, many of whom ended up in Auschwitz and Sachsenhausen. Operation KUTSCHERA was carried out by the Polish underground Kedyw (sabotage) by members of the Grey Ranks scouts. Known as the ‘Butcher of Warsaw’ he oversaw the roundups of civilians as hostages to reduce AK attacks on the occupying Germans (Lukas, 1997). After the assassination, hundreds of Poles died in reprisals despite a bounty being offered for the perpetrators arrest and capture, few of the original team survived the action. Anton Hergal, the Nazi commissioner who controlled the press was wounded twice in 1943. Others who were targeted included:

- Herbert Schultz, SS Obersturmführer assassinated 6th May 1943.

- Ernst Lange, SS Tottenfürher 22nd May 1943 by the Kedwy Battalion Zośka.

- August Kretschmann, SS Hauptscharfürer who commanded the concentration camp in Gęsiówka prison in Warsaw on 24th September 1943.

- Ernst Weffels, SS Sturmann, part of the Pawiak Prison personnel for his role in torture and cruelty to women prisoners.

- Albrecht Eitner, an agent for the Abwehr assassinated on 1st February 1944.

- Willy Lübert and Walter Stamm, were responsible for organizing the roundups (łapanka) for slave labour camps on 1st February 1944 and 5th May 1944.

- Karl Freudenthal, Kreishauptmann for the murder of Poles and deportation of Jews on 5th July 1944.

These actions indicated no officers or collaborators were ‘safe’ and maintained tension for the occupiers and fear amongst the collaborators. As part of the AK’s sabotage and diversionary actions, the Wehrmacht and the SS were forced to allocated badly needed troops for the Eastern Front into occupation duties and counter-partisan actions across occupied Poland, tying up badly needed reserves as the tide of war turned in 1943.

The Japanese Connection:

An outstanding operation was the cooperation between Poland and Japan as an unlikely ‘bed-fellow’. Japan had recognised Poland after the Treaty of Versailles> and instructed Sugihara Chiune who was based in Helsinki between 1937 and 1939 and then posted to Kaunas between 1939 and 1940 (Krebs, 2017; Pałasz-Rutkowska, 2022) into intelligence gathering against the Soviets. The Polish agents were issued with Japanese or Manchurian passports with diplomatic immunity. Although some agents were arrested, the network aided Jews escaping persecution as well as collecting economic and military intelligence on the German preparations for war in Königsberg (Kaliningrad) against the Soviets.

The Polish - Japanese network also operated out of Sweden’s Station ‘Anna’ and substation ‘Północ’ (Pepłoński, 2005b; McKay, 2020) and the cooperation evolved out of the need for the Japanese to decipher intercepted Soviet cables during the 1920s (Pałasz-Rutkowska, 2022). The degree of cooperation extended towards training in Poland with Capt. Terada Seiichi with the Polish 2nd Air Regiment. Pałasz-Rutkowska (2022) estimated more than a hundred officers and non-commissioned officers attended these intelligence training courses during the inter-war years to assist in gathering intelligence for the Poles on Soviet activities. Indeed, the Japanese Attaché Yamawaki acted as an intermediary between Germany and Poland to reduce pre-war tensions regardless of Poland’s resistance to their proposals.

Col. Nishimura, the Japanese Military Attaché in Stockholm also provided shipping and naval intelligence gathered in Haparanda and Boden (Pepłoński, 2005b; McKay, 2020) after the outbreak of war that acted against Japan’s neutrality.

Ambassador Tadeusz Romer played a key role in the cooperation between Poland and Japan despite uncertainty when Germany signed a non-aggression pact with the Soviets on 24th August 1939 upending the Anti-Comintern Pact the Poles and Japanese had signed on 6th November 1937 (Pałasz-Rutkowska, 2008). The net effect was to strengthen Japan’s support for stronger diplomatic ties, assisting in funding Polish (Jews) refugees through obtaining exit or transit visas to Japan and funded relief work for interned Poles in the Soviet Union (Pałasz-Rutkowska, 2017).

Although Stockholm became the centre of operations, other centres had been in Kaunas, Berlin and Königsberg with envoys also representing Polish interests in the Vatican, the Balkans and Manchuria. Stalin had been deeply concerned over the level of cooperation between the two countries (Kuromiya, 2009) while a much larger Soviet deception game was being played out. However, the relationship was complex and while Poland shared intelligence with the Allies, the Japanese also shared intelligence with the Germans exposing the relationship to potential misleading or black propaganda entering the system (Pałasz-Rutkowska, 2022). The role of the Japanese assisting the Jewish community should not be overlooked and remains significant in the story of the holocaust. This relationship seems contradictory to the events that occurred in the Pacific that overshadowed Japanese involvement in Europe and Scandinavia.

Selected References

Anon (2012) “Espionage Among Officers of the Polish Army 1918-1939”, https://www-konflikty-pl.translate.goog/historia/1918-1939/szpiegostwo-wsrod-oficerow-wojska-polskiego-19181939-czesc-druga/?_x_tr_sl=pl&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc (Accessed 22.02.2024)

Adamczewski, P. (2019) “Several Documents on German and Georgian cooperation during the interwar period and World War II are kept in the Polish archives in London – Part II”,Sensus Historiae, Vol. XXXIV, No.1, pp.25-48.

Bergen, D.L. (2008) “Instrumentalization of Volkesdeutschen in German Propaganda in 1939: Replacing/ Erasing Poles, Jews, and Other Victims”, German Studies Review, Vol. 31, No.3, pp.447-470.

Bielak, M. (2019) “Ewakuacja żołnierzy polskich z Francji do Wielkiej Brytanii i Afryki Północnej w latach 1940–1941”, OBEP IPN, Poland.

Budiansky, S. (2000) “Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War II”, Viking, UK.

Ciechanowski, J.S. (2005) Literature on the Activities of Polish Intelligence in World War II”, in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch5.

Davies, N. (2001) “Heart of Europe: The Past in Poland’s Present”, OUP, UK.

CDavies, N. (2003) “Rising’ 44: The Battle for Warsaw”, Macmillan, UK.

Eberhardt, P. (2011) “Migracje Polityczne Na Ziemiach Polskich (1939 – 1950”, Polska Akademia Nauk Instytut Geografii I Przestrzennego Zagospodrowania, Poland.

Heim, G. (2022) “Secret Agents at Lake Geneva”, ETH Library, Switzerland (Accessed 29.02.2024)

Kochanski, H. (2012) “The Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War”, Allan Lane, UK.

Komaniecka, M; Samonowska, K; Szpytma, M and Zechenter, A. (2013) “Katyn Massacre – Basic Facts “, The Person and the Challenges, Vol.3 No.2, pp.65-92.

Korkuć, M (2019) “The Fighting Republic of Poland 1939-1945”, IPN, Poland.

Krebs, G. (2017) “Germany and Sugihara Chiune: Japanese-Polish intelligence cooperation and counterintelligence”, Deeds and Days, pp.215-230.

Kuromiya, H and Pepłoński, A. (2009) “The Great Terror: Polish – Japanese Connections”, Cahiers du Monde Russe, Vol. 50, No. 4, pp.647-670.

Kuromiya, H. (2021) “Jerzy Niezbrzycki (Ryszard Wraga) and the Polish Intelligence in the Soviet Union in 1930s”, Przegląd Historyczno-Wojskowy, No. 4, pp.190-207.

Landmann, T and Bastkowski, P. (2017) “Manifestations of Closer German-Soviet Political, Economic and Military Relations, in the Years 1921-1926, from the Perspective of the State Security, as assessed by the Second Department of the General Staff of the Polish Armed Forces”, Tadeusza Kościuszki Journal of Science of the gen. Tadeusz Kosciuszko Military

Academy of Land Forces, Vol. 49, No. 2, pp.16-32.

Lukas, R.C. (1997) “Forgotten Holocaust: The Poles Under German Occupation 1939-1944”, Hippocrene Books, USA.

Machnak, A. (2017) “Polish military intelligence and counterintelligence activities against the Soviet Union 1918-1939: a description of operations from the files of the main directorate of information of the Polish army”, UR Journal of Humanities and Sciences, DOI: 10.15584/johass.2018.1.1

Maresch, E. (2005) “Polish Radio Intelligence Service and Sigint”, in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch47.

McKay, C.G. (2020) “From Information to Intrigue: Studies in Secret Service Based on the Swedish Experience, 1939-1945”, Routledge, UK.

Morriss, A. (2015) “The BBC Polish Service During the Second World War”, Media History, Vol.21, No. 4, pp.459-463.

Morris, J. (2004) "The Polish Terror: Spy Mania and Ethnic Cleansing in the Great Terror”, Europe-Asia Studies, Vol.56, No.5, pp.751-766.

Mulligan, T.P. (1987) “Spies, Ciphers and ‘Zitadelle’: Intelligence and the Battle of Kursk, 1943”, Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 235-260.

Napora, A. (2016) “German non-governmental organizations operating for the Abwehr in Poland in the years 1918-1927”, Journal of Science of the Military Academy of Land Forces, Vol.48, No. 4, pp.46-61.

Nowak, J. (1983) “Courier from Warsaw”, Wayne State University Press, USA

Ochał, A. (2018) “Problemy żandarmerii Korpusu Ochrony Pogranicza z marynarzami Flotylli Pińskiej w 1927 r. Przyczynek do historii formacji w świetle dokumentów żandarmerii KOP”, Przegląd Historyczno-Wojskowy, Vol. XIX, No. 3-4, pp.98-113.

Pepłoński, A. (2005) “Co-operation between II Bureau and SIS”, Intelligence Co-Operation Between Poland and Great Britain During World War II”, The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee, Vol. 1, pp.181-197.

Pałasz-Rutkowska, E. (2008) “Ambassador Tadeusz Romer. His Role in Polish - Japanese Relations (1937-1941)”, Silva Iaponicarum, No. XVIII, pp.82-138.

Nowak, J. (1983) Pałasz-Rutkowska, E. (2017) “The Polish ambassador Tadeusz Romer – a rescuer of refugees in Tokyo”, Deeds and Days, Vol. 67, pp.239-254.

Pałasz-Rutkowska, E. (2022) “Intelligence Cooperation Between Poland and Japan During the Second World War”, Prace Historyczne, Vol. 149, No. 2, pp.319-342.

Pepłoński, A. and Suchcitz, A. (2005a) “Organisation and Operations of the II Bureau, of the Polish General Staff), in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch9.

Pepłoński, A. (2005)“Scandinavia and the Baltic States”, in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch34.

Peszke, M.A. (2011) “The British-Polish Agreement of August 1940: Is Antecedents, Significance, and Consequences”, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp.648-658.

Rogalski, W. (22017) “Divided Loyalty: Britain’s Polish Ally During the Second World War”, Helion & Co, UK

Salata, O. (2020) “The Radio Propaganda as an Innovative Element of the Military Tactics and Strategies of the Nazi Germany 1933-1941”, SKHID, No. 2 (166), pp.42-47.

Salata, O. (2020) “The Radio Propaganda as an Innovative Element of the Military Tactics and Strategies of the Nazi Germany 1933-1941”, SKHID, No. 2 (166), pp.42-47.

Siewier, M. (2020) “Polish-German Struggles for Influence in Upper Silesia During the Sanitation Period (1926-1939)”, Humanities and Social Sciences, Vol. XXV, No.27, pp.111-123.

Simic, B. (2010) “Radio Service of the State Propaganda During the 1930s, Cases of Poland, Yugoslavia and Bulgaria”, TОКОВИ ИСТОРИЈЕ, Vol.3 pp.37-54.

Skóra, W. (2004) “The Cooperation between the Consular Services 0f II Republic and Military Intelligence”, The Polish Foreign Affairs Digest, Vol.4, No.3, pp.169-205

Skóra, W. (2019a) “Okno na świat” i „dwójka”. Działalność placówki polskiego wywiadu i kontrwywiadu wojskowego w Gdyni w latach 1933-1939”, Przegląd Zachodniopomorski, Vol. 34, No. 2, pp.99-131.

Skóra, W. (2019b) “Polish Diaspora and Military Intelligence of the Second Polish Republic 1918-1939”, Studia Polonijne, T.40 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18290/sp.2019.11.

Świerczek, M (2019) “Intelligence infiltration of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs by Soviet intelligence”, Przegląd Bezpieczeństwa Wewnętrznego, Vol. 11, No. 20, pp.258-279.

Triantafyllopoulos, C. (2020) “The Codes of the Polish Intelligence Network in Occupied France”, http://chris-intel-corner.blogspot.com/2015/04/the-codes-of-polish-intelligence.html (Accessed 01.03.2023).

SWidacki, J. (2021) “Major Ludwik Krzewiński, MD – the Creator of Polish Narcoanalysis”, European Polygraph, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp.41-51.

Widacki, L. (2022) “Ludwik Krzewiński – Creator of Polish Narcoanalysis”, Miscellanea Historico-Iuridica, Vol. XXI, No. 2, pp.203-222.

Winter, P.R.J. (2011) “Penetrating Hitler’s High Command: Anglo-Polish HUMINT, 1939-1945”, War in History, Vol.18, No.1, pp.85-108.

Wnuk, R. (2005) “Polish Intelligence in France 1940-1945”, in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch21.

Vitti, E. (2014) “Propaganda in Poland 1938-1945. The Conditioning of the Masses Between the Reich and the General Gouvernement”, Il Politico, Vol. LXXIX, No.2, pp.216-233.

Additional References:

Bretan, J. (2022) “This is London: The Wartime Story of the BBC Polish Section”, Culture.pl (Accessed 29.02.2024).

Briggs, A. (1995) “The War of Words: The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom: Vol. III”, OUP, UK.

Campbell, K.J. (2011) “A Swiss Spy”, American Intelligence Journal, Vol. 29, No. 2, pp.159-162.

Champion, B. (2011) “Heidi and Seek: Cases of Espionage and Covert Operations in Switzerland, 1795-1995”, Swiss American Historical Society Review”, Vol.47, No. 2, pp.1-18.

Ciancia, K. (2020) “On Civilization’s Edge: A Polish Borderland in the Interwar World”, O.U.P, UK.

Korbonski, S. (2004) “Fighting Warsaw – Story of the Polish Underground State 1939-1945”, Hippocrene Books, USA.

Newcourt-Nowodworski, S. (2020) “Black Propaganda: In the Second World War”, Sutton Publishing Ltd, UK.

Tremain, D. (2018) “Double Agent Victoire: Mathilde Carré and the Interallié Network”, The History Press, U.K.

Zaniewicki, W. (2007) “L'armée polonaise clandestine en France (1942) d'après des archives inédites”, Verites Pour L’Histoire, France.

Selected Websites:

https://www-konflikty-pl.translate.goog/historia/1918-1939/szpiegostwo-wsrod-oficerow-wojska-polskiego-19181939-czesc-druga/?_x_tr_sl=pl&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc

https://operacja-polska.pl/nke/about-polish-operation/document/857,11th-August-1937-Moscow-Operational-order-No-00485-of-the-Peoples-Commissar-for-.html

https://warsawinstitute.org/phenomenon-polish-underground-state/

https://polishhistory.pl/operation-kutschera/

https://warsawinstitute.org/home-army-liquidation-operations/

https://culture.pl/en/article/this-is-london-the-wartime-story-of-the-bbc-polish-section

https://www.cbc.ca/radio/asithappens/as-it-happens-tuesday-edition-1.5277837/high-stakes-stuff-how-the-bbc-aided-the-resistance-during-ww-ii-using-music-1.5277845

https://blog.nationalmuseum.ch/en/2022/01/red-three-at-lake-geneva/

Selected Films

“Bay of Spies” (Zakota szpiegów), (2024) Directed by Michał Rogalski with Bartosz Gelner, Karolina Kominek, Mariusz Bonaszewski, Wiktoria Supryn, Michał Balicki, Maria Świłpa, Anna Radwan, Karol Pocheć and Anna Karczmarczyk.

“Enemy of My Enemy” (NK) New film about Capt. Witold Pilecki and the resistance in Auswitz and produced by Jayne-Ann Tenggren.

(NK) Directed by James Marquand with Morgane Polanski, Frederick Schmidt, Agata Kulesza, Ingvar Sigurdsson and Malcolm McDowell.

“Secret Enigmy” (1979) Directed by Roman Wionczek with Tadeusz Borowski, Piotr Fronczewski, Piotr Garlicki, Tadeusz Pluciński, Jerzy Kamas and Janusz Zakrzeński.

YouTube Clips

– Mathilde Carré

– BBC’s Secret War

- Enigma

– Sefton Delmar – Master of Black Propaganda

– Pathé news reel 1939

– Polish troops arrival in Britain as a reminder

| |