SOE, Poles and the Balkan Connection

Background

A network of Polish communications, couriers and agents stretched throughout Hungary, Yugoslavia, Albania, Turkey to Greece. SIS and SOE were aware of the network particularly when coded ciphers sometimes ended up in the wrong hands within British Intelligence whether it was SIS, SOE or the Foreign Office (FO) (TNA/ HS4-234). Such was the size and locations of the network that SOE in Cairo made a request on 31st January 1942 if any personnel were available for 5th Column work in the Balkans and Hungary (TNA/HS4-234) since some 25,000 people of Polish extraction lived in Yugoslavia. Those SIS or SOE agents that were selected were given little time to prepare or research their proposed operational areas with a distinctive lack in knowledge of languages and geographical factors let alone culture, politics or socio-economic facts (Hibbert, 2001).

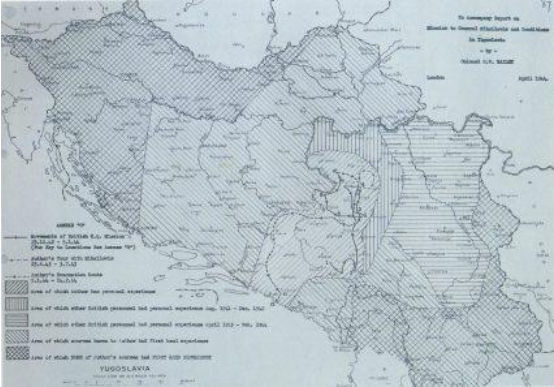

Britain’s overall strategic policy and planning for Yugoslavia, Albania and the Balkans appears at first hand to be one of duplicity or as in the case of Yugoslavia, confusing and contradictory (Barker, 1976). In realpolitik, it was akin to military success based on financial and military ‘returns’ and ‘efficiency’. End result, SOE supported the anti-communists in Greece and the communists in Yugoslavia and Albania (Foot, 1990) using ‘shadow missions’ initially led by Major L. G. Barbrook (Atkin, 2021). OSS had access to intelligence from SOE and SIS, but felt they lacked the quality in leadership and the need for unity in a command structure for campaigns in the latter stage of the war where Churchill’s choice in backing Tito still resonates today (Duke; Phillips, and Conover, 2014).

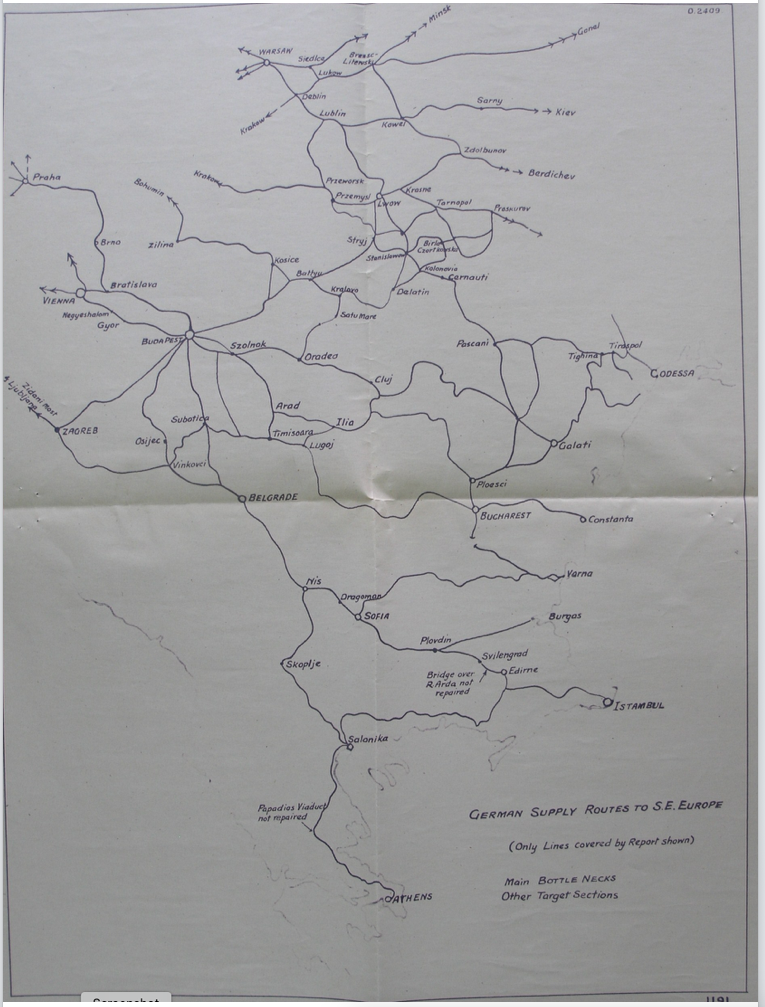

Britain’s interests in Yugoslavia stemmed from the strategic value of their lead, chrome and zinc mines and the River Danube transporting oil from Romania to Germany (Atkin, 2021). For Albania and Bulgaria, SOE lacked local knowledge or networks for any meaningful strategy to develop at the out-set of war. Prior to the German invasion of Yugoslavia, MI(R) had identified key points on the transport network for demolition or mining (Ogden, 2010; Atkin, 2021) and was unaware SIS had a long-standing intelligence gathering operation there through an agent Julius Hanau who had good contacts within the Royal Yugoslav Army.

Yugoslavia

The invasion of Yugoslavia started on 6th April 1941 under the code name APRIL WAR or OPERATION 25. Although the German Wehrmacht led the planning and invasion, it was an Axis attack that took advantage of the instability of the country after a coup d’etat on 27th March 1941 when the Regent Prince Paul of Yugoslavia was overthrown by King Peter II with the assistance of General Simović and minor support from SOE. King Peter II was related through marriage to the Duke of Kent’s sister in-law, and it was assumed he would be pro-British (Foot, 1990). Mussolini had invaded Albania between 7-12th April due to its strategic position in controlling the Adriatic Sea and had also been an Italian Protectorate between 23rd June 1917 to the summer of 1920 with long cultural links to Italy spanning centuries. Italy was tasked to enter Yugoslavia through Ljubljana, the disputed territory of Slovenia that had been ravaged in World War 1 between Italy and Austria. The German multi-pronged attack from Romania, southwestern Bulgaria, Ostmark (then part of Germany) and Hungary quickly overwhelmed the Royal Yugoslav Airforce. The sudden collapse of the Royal Yugoslav Army offered little resistance in many regions. The Armistice of 17th April 1941 was an unconditional surrender which saw the country partitioned by the Axis powers based on geographical, historic and lose cultural claims.

General Simović’s rule was very short-lived and with the collapse of the Yugoslav forces. A Serb Officer Colonel Draža Mihailović, had fled to the hills just south of Belgrade and messaged for British assistance (Foot, 1990). SOE responded by sending in a mission BULLSEYE via a submarine (HMS Triumph) Maj. D.T (Bill) Hudson (Marko) a mining engineer with no experience of guerrilla warfare but experienced in sabotage operations in Greece and Turkey including the sinking of two Axis merchant ships by limpet mine in Split harbour (TNA/PRO/ HS9/758/1); three Yugoslavs: Majors Ostojić and Lalatović, and W/T operator Sgt. Veljko Dragićević with two WT sets (Foot, 1990). Once ashore at Petrovac, they made their way inland and ran into a partisan group led by Tito (Josip Broz) who allowed them to continue their mission to Mihailović despite a civil war raging in Yugoslavia. Tito’s partisans were fighting Mihailović’s Četniks and the Axis Army, notably the Germans assisted by Italians and Bulgarians. Hudson’s task was to contact all parties irrespective of religious, national, or political beliefs to unite them against the Axis powers.

The struggle between Tito and Mihailović was entrenched and developing a rationale for policies by SOE was hampered by inconsistent reports received from Hudson (Foot, 1990). These inconsistencies and the breakdown of Mihailović’s broadcasting system led to a communications support operation COLLABORATE in the autumn of 1942 where Capt. Peter Lofts (TNA/ PRO/ HS9/934/6) would improve the organisation of ciphers for security and W/T traffic (TNA/ PRO/ HS5/ 888). Two planes were allocated for the drop at Sinjajevina mountains in the north of Montenegro on 26th September 1942 with additional clothing supplies and four W/T (type Collins) sets and batteries with 14,450,000 Liras, £10,000 in gold to support the existing team in the field and not destined to support Mihailović (TNA/ PRO/ HS5/ 888). Each plane was to fly with fifteen minutes separating them. The team also included two W/T operators (Sgt. Ainworth and Sgt. Emly) and a Yugoslav Cpl. Boris Slamnik (his sister was living in Slavonski Brod, Croatia) to be dropped 17Km northeast of Kolašin. Both W/T operators were injured with Ainsworth receiving a fractured ankle and Emly badly bruised with no injures to the other two. The canisters landed within 50 metres of the fires lit by the reception party on the LZ with some minor damage to the contents due to the parachutes being less effective in protecting the contents, but not the W/T sets. Somehow some of the batteries were missed from the supply drop. Capt. Lofts was to brief Hudson’s team and Mihailović that imminent victory in Libya would release Allied soldiers and equipment, however, these missions needed to be prepared for imminent invasion spearheaded by the Germans. The need to expand cells in Croatia, Bulgaria, and Albania was high on the agenda for the team. Mihailović pressured the team to hand over W/T sets and the cash which was rejected by Hudson on instructions from Cairo. Hudson who became fluent in Serbo-Croat having worked in Yugoslavia pre-war (TNA/ PRO/ HS9/758/1) was informed that Capt. Lofts needed to set up and support propaganda broadcasts through encouraging Mihailović to collect any relevant stories, local events, and news so that the transmissions looked genuine while also including propaganda (TNA/ PRO/ HS5/ 888). Hudson’s mission was rebuffed by Tito and undermined by two SIS agents sending separate reports. A poorly organised HQ became a recipe for disaster to the mission and may have ultimately led to SOE focussing on Tito (West, 2019), however Hudson was ‘politically aware’ and recognised support for Tito was beneficial in that over 100,000 Serbs fighting a guerrilla war would pin down valuable divisions (TNA/ PRO/ HS9/758/. Hudson also recognised Tito was ‘active’ whereas Mihailović a passive resistant leader. Hudson survived the severity of poor communications and resupply, harsh winters, and hardships to be extricated in early 1944 by plane, flown to Bari and then Britain for briefing of the

FRESTON Mission.

There is evidence to suggest that disinformation within SOE added to Churchill’s ‘blunder’ in switching support to communist led Tito’s forces. There is evidence to suggest that SOE base in Cairo (SO(M)/ Force 133) fed deliberate distorted information and sabotaged relations to convince London to abandon Mihailović for Tito through the activities of James Klugmann a committed communist and probable Soviet agent (Kemp, 1958; Martin, 1990; Bailey, 2005). While this stance has merit, the final choice was taken on military grounds, not political, however Foot (1990) suggested it was Keble who lobbied for Tito with Klugman’s input to the change strategy which was according to Bailey (2005) was of little importance. Ultra-traffic indicated Mihailović was too close in friendship with Italian supported Ustaše, a Croatian fascist ultranationalist party supporting the Axis powers (Foot, 1990) whereas Tito was fighting on multiple fronts more effectively especially against the Germans. Both men had a different end game goals for Yugoslavia: Tito a communist state and Mihailović a Serb dominated kingdom. The result was for Brigadier Fitzroy Maclean who acted as Churchill’s personal envoy to be attached to Tito and Brigadier Armstrong to Mihailović. Armstrong was under pressure to stop Mihailović harassing Tito’s partisans through being rewarded arms supplies. Maclean was instructed to confirm if Tito’s republic HQ was based in Užice, along with his military strength and locations of sub-camps while also discussing Tito’s post war political position (TNA/ PRO/ HS5/888). It was also suggested there was another way of funding operations in Yugoslavia through a mad-cap scheme to contact Dr Vlada Markovitch, former president of the Izvozna Bank in Belgrade. Through an intermediary (referred as Miss M) any Dinars used would be supported by an equivalent sterling sum deposited into a London bank. Miss M and the Markovitch family could leave Belgrade via Istanbul and eventually return to southern France where they had a villa in Nice (TNA/ PRO/ HS5/888). Unfortunately, this section of the archive does not indicate what the outcome was.

The Polish II Bureau had set up a cell in Belgrade in March 1940 after the ‘Romek’ base in Budapest had been evacuated after the Hungarian Intelligence had arrested members of the cell (Przewoźnik, 2005). Belgrade was a natural choice since several courier and escape routes passed through Yugoslavia. Belgrade was staffed by former Romek staff: Captain Władysław Guttry (Grot), Captain Tadeusz Werner (Ostoja) and W/O Zygmunt Burghardt (Lipcyński) setting up cell Sława (Przewoźnik, 2000). The cell was commanded by Major Wiktor Zahorski (Tramp) who arrived from Budapest in August 1940 and then later by Captain Władysław Guttry who with his brother Kazimierz set up a post in Jagodina in central Serbia (Przewoźnik, 2005) that experienced a break in regular communications. Co-operation and communications improved with the arrival of Captain Jerzy Szymański from the ‘Muł’ Base in Cairo to reactivate courier routes and work with Mihailović (Przewoźnik, 2005). In addition, Capt. Szymaniak who resided in Belgrade under French citizenship as Victor Senner, was known to SIS and after his departure, Countess Potocka carried on intelligence gathering that was passed through the Vatican to London (Bennett, 2005).

SIS were also active within the region from early 1942 handling W/T traffic for SOE and thereby having access to signals (Ritchie, 2004). Access to some regions were more difficult adding to the complexities of communications, networks and arms drops. SIS infiltrated Maj. Novak to act as a representative (Inter Services Liaison Department /ISLD) for Mihailović in Slovenia, however, Ritchie (2004) suggested there is evidence that some members of SIS were prejudiced towards the communist partisans which left operational gaps until May 1943 when a cipher given to SOE indicated partisans had killed 3,000 non-communist Slovenes and only 100 occupying troops. Reliability of reports was an issue and the priority seemed to confirm action against Axis troops and installations was a lower priority in the civil war which was exasperated through a shortage of air transports to meet the demand made from field agents which began to ease in February 1942 when special duties aircraft moved to Darna in Libya.

SIS and SOE carried out joint operations within Yugoslavia. The first, FUNGUS was a blind drop near Drežnica on 20th April 1943 and made their way to partisan HQ in Brinje, Croatia. The party consisted of Yugoslav emigres Alexander Simić-Stevens and two Yugoslav Canadians, Petar Erdeljac and Pavl Pavlić, who were recruited by the SOE and trained at Camp X in Canada (Off, 2004). HOATHLEY I, followed the same night as a backup to FUNGUS and consisted of Steven Serdar, Milan Druzic and George Diklic former miners trained in sabotage (Petrou, 2018; West, 2019). On 18/19th May 1943 they were joined by Maj. Anthony Hunter (FUNGUS) who acted as a BLO to the Croatian partisan HQ with W/T operator Sgt Ronald Jephson. Major Jones travelled on to Slovenia on a sabotage mission. The second group landed during the German offensive FALL SCHWARZ or the Battle of the Sutjeska making the mission more hazardous throughout June 1943.

FALL SCHWARZ was an Axis counter-partisan operation that started on 15-16 May 1943 and set out with three phases to destroy the partisans near Sutjeska in south-eastern Bosnia and capture Tito. Mistrust and misunderstanding resulted in key differences between the Italians and Germans where it was felt necessary by the Germans to disarm the Četniks. The operational plan was adjusted to the local terrain where artillery and planes supported the actions in the region between Tara and Piva canyons and Durmitor mountains. The 1st Mountain Division, the battle group LUDWIGER, 369th Infantry Division and supported by Bulgarian and Croatian units formed a semi-circle with the escape over the Piva river blocked.

The initial battle 15-20 May saw Axis troops encircle the partisans in the Durmitor mountains that resulted in a war of waste and attrition leaving civilians to seek shelter in the forests and mountains. The partisans broke out towards eastern Bosnia 21-27 May and escaped the encirclement near Foča suppressing counterattacks. 118th Jäger Division tasked with blocking an escape route over the river Piva proved ineffective when partisans broke out near Vučevo situated on a plateau west of Piva that resulted in turning the 118th Jäger Division towards Sutjeska. On 18th May 1943 the 7th SS Volunteer Mountain Division Prinz Eugen and the Italian Division Ferrara moving north towards Šavnik, met stiff resistance from the First Dalmatian and the Fifth Montenegrin Brigades. On 27th May 1943 the British military mission TYPICAL, an ISLD operation led by Col. William Deakin and Capt. William F. Stuart accompanied by two W/T operators Sgts. Walter Wroughton and Peretz (Rose) Rosenberg (from the Jewish Agency), Ivan ('John') Starčević (translator) and Sgt. John Campbell cipher clerk and bodyguard were parachuted in (Ritchie, 2005; West, 2019) and moved to Tito’s HQ to assist in the co-ordination of operations with the partisans. They were tasked to liaise between the partisans and any future major offensives by the Allies. Captain William F. Stuart was killed during an air-raid on 6th June and the group successfully broke out of the encirclement near Tjentište later on the 13th June 1943.

In March 1942 The Polish II Bureau changed the Sława cell to Drawa and to be commanded by Captain Józef Maciąg (Wala) under the code name of Captain Nash who was parachuted into Homalijska Planina in eastern Serbia on 15-16 June and later joined Mihailović troops. Capt. Józef Maciąg extended the networks across the region and were called: Pristina, Ohrida and Larissa (Przewoźnik, 2005) and were effective in their role.

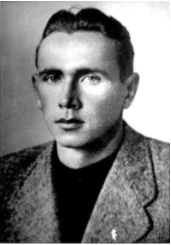

Capt. Józef Maciąg or Nash (Wala) (TNA/HS 9/1086/3) key task was to set up radio contact through SOE in Cairo and allow access to Polish networks (Przewoźnik, 2005) while attached as a PLO/ BLO to the partisans. At the outbreak of war, he was a second lieutenant and had served in the September Campaign as a soldier in the 34th Infantry Regiment and fought near Kock in defence of Brześć in eastern Poland. Having escaped to Palestine through Romania, Hungary, and Yugoslavia he joined the Independent Carpathian Rifle Brigade in the Middle East. In 1943, he joined the British SOE and parachuted into Albania on 15th June 1943 as a BLO to partisans in Holmolje region in eastern Serbian in operation HARBOURNE (Maresch, 2005).

EXCERPT was dropped on 21st May 1943 consisting of Capt. Rootham, Lt. Hargreaves and Cpl. Hall as W/T operator and report to Maj. Greenwood who commanded the area. It was scheduled that the team would join the Četniks under Maj. Piletic. The focus of the sabotage operations was to attack shipping on the Danube, the Bor Copper mine and any Axis supply lines by road and rail transport covering the area around Negotin with expectation to penetrate Romania and Bulgaria. Greenwood, a Cambridge graduate of 1932 also studied at the Sorbonne, Paris and in Berlin specialising in economics (TNA/ PRO/ HS9/617/7) had some fluency in several languages including Serbo-Croat. As a BLO had worked hard at his role for fourteen months and was respected by the Četniks. Capt. Rootham’s team set up the reception committee in the Homolje region for operation RANJI on 15-16 June 1943 whose mission was to penetrate Bulgaria that ended in disaster when the mission leader, David Russel (Albert Thomas) was murdered (Ogden, 2010).

The mission was to be supplemented by operation EXCERPT 13 (formally ALLEGORY/ HARBOURNE) (TNA/ PRO HS5/ 889) scheduled for September 1943 when weather and conditions permitted to reinforce the missions in the Homolje area. The reception committee would be under the command of Major Jasper Rootham and the mission lead Capt. Vercoe (Cove), would be under Rootham’s command. The primary objective was in the transfer of mail and intelligence from Poland bound for Cairo via Istanbul with the secondary task of rounding up any escapees or Polish POWs. Co-operation with local BLO’s and Četniks for sabotage and collection of intelligence was also required. W/T traffic would be through Capt. Nash to Cairo and then transferred to the Poles at T.O.K, the Poles HQ.

Hargreaves and Rootham were active within the region with the archives indicating eighteen different attacks despite the brutal retaliation by the Germans upon the local Serb population (TNA/PRO/ HS9/1086). The engagements covered:

- On 13th September attacked a German column at Knjazevac capturing twenty Germans

- the blowing of the railway station at Rabrovo on 23rd September 1943 near the Bulgarian-Serbian border where twelve trucks were destroyed

- 2nd October engaged German and Bulgarian troops at Slivar, 7Km from Zajecar

- 25th October with the Golubacki and Zvishki units attacked a Bulgarian column at the village of Misljenovac

- 29th October engaged the Vlar Russians at Klocevac

- Sunk 2 barges and damaged 2 ships on the Danube at Djerdap

- 5th November the Knjazevac Brigade in the vicinity of Jeliskovac ambushed the Germans with 11 dead, 14 wounded and 25 prisoners

- 20th October - anti-partisan engagement with 30 Germans in the village of Maliljubica

- 3rd November attacked a train near the Bor mine and disarmed 6 Germans and 5 Bulgars

Through these actions, it is clear the mission was in danger and on the run to escape any anti-partisan sweeps through the countryside. On 1st December 1943 a small band consisting of seven Poles, five Serbs, two Greek cooks, a British Sgt. W/T operator, and an escapee left their camp. The group consisted of Capt. “Miki” (Hargreaves), Capt. “Nesz” (Nash), Capt. Patterson, Maj. Eric Greenwood, Cpl. Giuseppe Vella, and Cpl. Cecil Ridewood (Signals) on a trip to the mountains near Luka. Cpl. Vella was an unusual member of the group. A Doctor of Literature from the University of Rome and of Italian-Greek descendants, he had been expelled as an ‘undesirable alien’ from France for communist activities in 1932 (TNA/ PROHS)/1525/7). This mission was possibly code name RUPEE.

On 11th December, the group had been in the village for just a few days when a German attack caught them by surprise. Hargreaves was ill and bed-ridden and trapped in the hut under machine gun fire and later caught. Although the guards started the defence of the village, Nash was killed in action and only the W/T operator Rada and a few Poles escaped. The mission was stripped of stores and the W/T set and ciphers had been captured. They had possibly been betrayed or caught through RDF scans (TNA/HS 9/1086/3). Hargreaves was taken to the Gestapo prison in Belgrade, interrogated and sentenced to death before transfer to Buchenwald where it was accepted, he was a British officer, and then transferred to Colditz under the protection of the Red Cross.

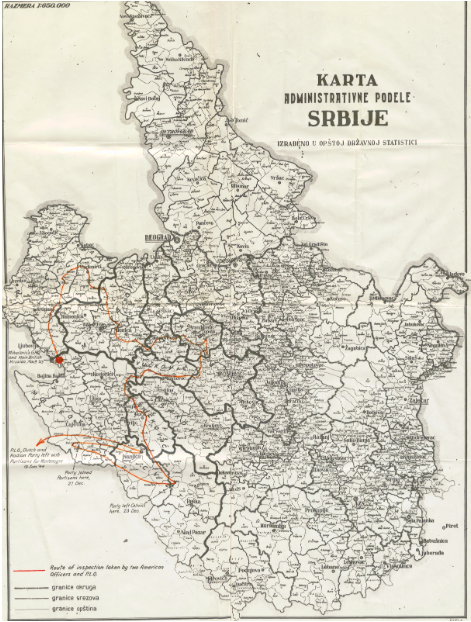

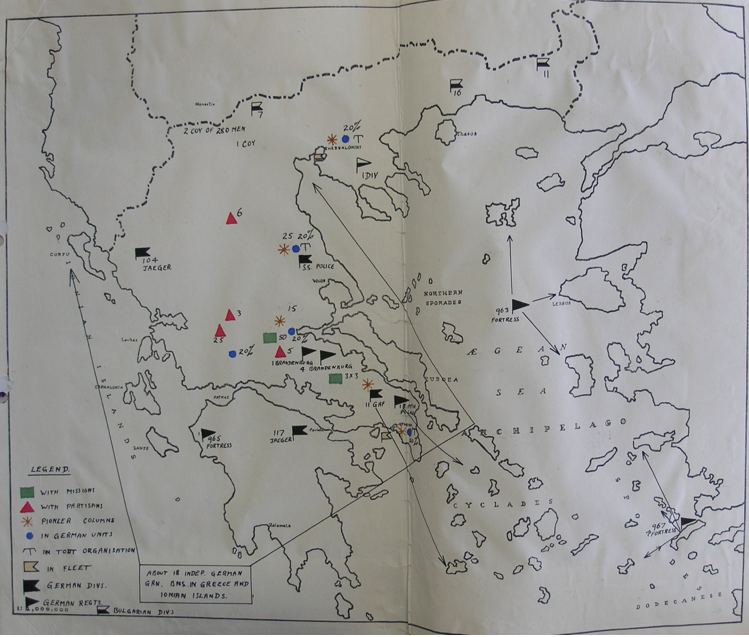

Known locations of SOE operations in Serbia (HS7/202)

The FUNGUS operation followed the move of the partisan HQ to Otocac commanded by General Ivan Gosnjak. He commanded the 4,6,10 and 11 army corps and the British operation swelled with the arrival of other SOE/SIS officers in transit and escaped POWs. The role of FUNGUS enabled them to arrange for operation TYPICAL to be parachuted into Tito’s HQ in Montenegro. The team consisted of Maj. Anthony Hunter, four commandos and a W/T operator Corp. Jephson (Ritchie, 2004). Maj. Anthony Hunter remained in Croatia and later moved to Montenegro as a BLO to Petar "Peko" Dapčević commander of the Second Proletariat Division who had witnessed the Italian surrender at Berane in September 1943.

Italy’s capitulation in September 1943 enabled the partisans to consolidate their positions in Croatia and Slovenia through disarming six Italian divisions (Ritchie, 2004) with many Italians joining Tito’s forces. It was at this point Maclean felt the ‘tide of war’ turning (West, 2019) and resulted in MACMIS. Operation MACMIS was organized by SOE and ordered by Churchill to reappraise the role and effectiveness of Tito’s partisans. Maclean understood the need for a team to be equipped with a range of skills that in the field made them stand out for their quality in running the operation. The team consisting of Maclean, Robin Whetherly (SAS), Maj. Vivian Street, John Henniker-Major, Sappers Peter Moore, Donald Knight, and Mike Parker (supply and logistics), Gordon Alston, an intelligence officer, and with security covered by Sgt. Duncan, Cpl. Dickson, and Cpl. Kelly plus two W/T operators. Past experiences of teams being ambushed, murdered, and robbed (Ritchie, 2004; West, 2014; West, 2019) changed the emphasis of this operation’s composition. On 17th September 1943 the team was parachuted into Mrkonjić Grad and quickly moved to Jajce to meet Tito. Mclean set out the plan for supporting Tito through officers being sent to each of the main partisan HQs with W/T sets for communications, intelligence, and re-supply. Despite the Italian armistice, supply by sea was still an unknown at this stage. It became clear to Mclean that Tito’s post war ambition was for a Soviet supported communist republic irrespective of SOE’s support.

Operation JUDGE followed FUNGUS in a support role to Hunter. With the Italian capitulation, SOE were keen to improve material and Mission support to the partisans. On 12th October 1943 Hunter had arranged a resupply drop with a guard of partisans to stop pilfering. The choice of DZ was inappropriate for paratroopers had Hunter been informed (Ritchie, 2004). The team consisting of Maj. Owen Reed, Paul Stichman (Canadian origin acting as interpreter) and Sgt. Paddy Ryan became embroiled with Tito’s preferences for stores and not personnel and Reed became confined to Hunter’s quarters. It was only when a resupply Liberator crashed near the village of Kosinjski that Reed was allowed to participate in operations and on 11th November Tito granted permission for the JUDGE Mission to commence (Ritchie, 2004). Both operations merged under Hunter’s command while relations with the partisans deteriorated due to their demands for greater logistical support and realisation of an Allied invasion of Yugoslavia was now unlikely. Hunter’s position became untenable and left for Fitzroy Maclean’s base in Bosnia and eventually evacuated to Italy on 3rd December whose contribution to the mission and the partisans should not be underestimated (Ritchie, 2004).

At some point Hunter returned to Yugoslavia and was met by Kemp (1958) at Berane before his mission was evacuated. Reed continued with his mission where the workload became unbearable due to Stickman joining the partisans and the need to learn three foreign languages. Reed was now responsible for supply drops, organising resupply by sea, collection of intelligence, coding/ encoding ciphers, BLO work and accommodating SOE and ISLD agents in transit through the region (Ritchie, 2004). His work also included the evacuation of escaped POWs while coping with shifting bases to avoid German anti-partisan action and bombing by the remnants of the Luftwaffe based in Zagreb. Equally, Jephson was hard working and had to be exfiltrated by a Dakota from Krbavsko Polje near Udbina along with US aircrew as he needed medical attention (Ritchie, 2004). Eventually, an OSS officer from Tito’s HQ, Major George Selvig replace Reed on 7th May 1943 with his own evacuation at the end of June 1943 before he had completed a list of suitable ports and airfields for resupply runs. Returned to duty, again his exploits in supporting the partisans with supplies, removing wounded partisans, orphans and POWs to Italy was heroic and selfless. Having moved to a more secure area of the Mala Kapela mountains in January 1944, Reed established excellent relations with the partisans through his role with the ISLD. The German Spring Offensive against the Croatian partisans enabled valuable intelligence including captured cipher codes to be transmitted back to Bari.

During a lull in the spring fighting, Reed set out suitable DZ and airfields to improve mass landings and evacuation of valuable aircrew. In northern areas, starvation was evident with partisan requests for both food and medical supplies altering their logistics. The requests were accommodated through more resources and expanding air transport being granted to the bases in Italy and this made a huge impact on operations. Against this backdrop, the ever-present threat from German counter-partisan actions and the Luftwaffe kept the Croatian HQ of Gosnjak at Dunjak on high alert as the forests and mountains became the refuge for civilians too.

On the morning of 25th May 1944 Reed observed the mass formation of the Luftwaffe flying south from Zagreb for Tito’s HQ at Drvar supported by ground troops. An emergency signal produced a response that was timely despite Tito’s evacuation and subsequently Drvar was over-run (Kemp, 1958). Between 26-30th May over 1,000 sorties were flown by RAF and USAAF on selected targets through intelligence provided by Reed (Ritchie, 2004) with Allied air superiority altering the Yugoslav war. A substantial reduction in German action due to the Second Front and Allied landings in Normandy provided some temporary relief to the partisan forces. Reed again identified alternative landing strips at Gajevi for the evacuation of Allied airmen with the first flight arriving on 10th June 1944.

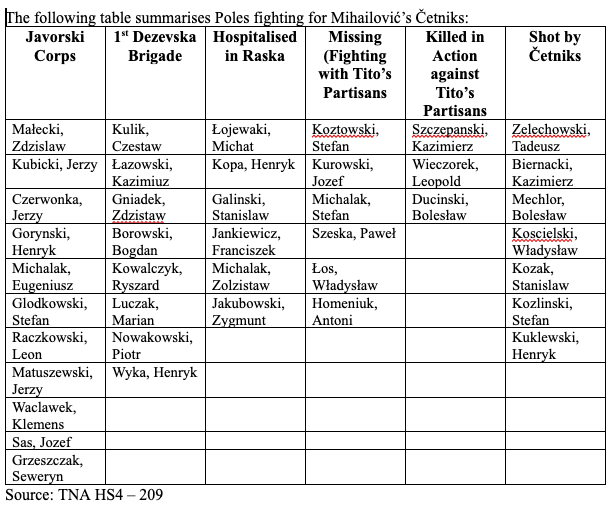

The conditions the Poles were fighting under with Mihailović’s Četniks were harsh and treated as inferior by the Četnik officers who felt the Poles did not deserve the same level of food. Such was the concern of using Poles against Tito’s partisans that Brigadier Armstrong passed his views onto No. 1 Special Force (TNA HS4 – 209) as these actions were damaging relations with Tito that forced an air evacuation of them and the British Mission in June 1944 that initially been blocked by Tito.

Slovenians conscripted into the Italian Army were re-trained and utilised by SOE through the ISLD working on reuniting the Primorska (Slovene Littoral) with Yugoslavia (Bajc, 2002) and ending conflict that started pre- World War 1. The Slovenians collected intelligence, manned W/T sets and acted as translators or interpreters passing information back to SOE and some partisan groups (Bajc, 2012). Although SOE failed to unite all potential resistance movements, nor preventing conflict between them (Bajc, 2002) their actions had a lasting effect on the missions and any degree of success.

In November 1943 General Gubbins had received reports from Capt. Patrick Howarth, a liaison officer to the Poles who thought that it was feasible to use Poles in Yugoslav operations (Przewoźnik, 2005). Przewoźnik (ibid) suggested the report was contentious due to the political situation within Yugoslavia, however it was also the eve of the Tehran Conference (28th November to 1st December 1943) and Stalin’s wish for Poland’s eastern border to be drawn upon the lines of Lord Curzon’s 1920 boundary submission to the Paris Conference 1919-1920. As a result, the Poles were withdrawn and Drawa’s activities ceased. The network had stretched from Yugoslavia, Romania, and Bulgaria on both sides of the Danube River.

Jan Kumosz (born in Kozara, Bosnia)

Jan Kumosz (born in Kozara, Bosnia) was working in Yugoslavia prior to the war as a teacher in Zagreb (base of II Bureau’s Station ‘J’). Promoted to captain, his battalion of 400 soldiers was based in the Kozarski Mountains where they fought both Mihailović’s Četniks and the Ustaša after fleeing across the river Vrbas. Several Polish units were transferred into the 14th Central Bosnian Shock Brigade which he commanded from July 1944. Their actions ranged from disarming Croats to the capture of the cities of Kotor-Varosa, Dervent, Lepenica and later Banja Luka. Post war, he worked with the new Communist government to resettle Poles who had fought in Bosnia to Bolesławiec in Lower Silesia, Poland. He entered the Polish parliament (Sejm) after the 1957 elections representing the Polish United Workers until 1961.

Major Aleksander Ihnatowicz- Świat (Turbina, Słonka, Ataman) at the outbreak of war was a Major in the cavalry reserve and after arriving in Britain became a weapons instructor at Audley End (STS 43) and Ostuni (OW No. 10) in Italy training Cichociemni. He had escaped from internment in Hungary and arrived in France and posted to an armoured motorized unit in Bollène based in the Vaucluse and Rhône Valley just north of Orange. Evacuated to Britain on 23rd June 1940 to Plymouth, he re-joined a mechanised unit the 14th Jazłowiec Lancers Regiment based in Scotland. He was then selected for specialist forces training at Inverlochy (STS 25) specialising in weapons and diversionary tactics and then posted to Audley End as an instructor to the Cichociemni. It appears there were personal issues while at Audley End that resulted in him transferring to the British Army as a 2nd Lieutenant ‘on loan’ for two years and shipped to Cairo and then Italy. From 8th November 1943 he was posted to Ostuni to train a specialist team to capture German armaments also. training 185th Italian Commando Battalion.

On 17th to 18th March 1944, he was parachuted into Yugoslavia in Zlatibor (held by the Četniks). The team managed to capture two FG42 machine guns developed for German paratroopers and delivered them to the village of Gruda near Dubrovnik in Croatia where the team were exfiltrated by submarine and returned to Brindisi.

Polish Intelligence had identified several Polish units in Tito’s territory fighting for the Yugoslav National Army of Liberation and partisan detachment. These were:

- Polish battalion attached to 13th Division of N.A.L in the Lika area in Croatia.

- Polish Engineers Coy. In the Lasinja – Kupa River area.

- Polish Battalion based in Bosnia with the N.A.L

In the Wehrmacht several units had significant of conscripted non-German elements:

-

104 and 107 Jaeger Divisions (30% made up of Ctech’s, Alsatians, Hungarians and Poles numbering 7,200

-

Poles conscripted in Landesschütz bataillonen (Territorial) 5,000

- Europeans in Todt organisation 5,000

- 2 Ostbataillonen (90% Eastern European) 1,400

- Italians used as auxiliaries and pioneers 10,000.

Attempts to join II Corps put huge pressure on individuals who were encouraged to formally join the N.A.L army (TNA/ HS4 – 206). Mihailović’s intransigence to release Poles forced the F.O to instruct Brigadier Armstrong to facilitate evacuation of the Poles otherwise his attitude and approach towards the Poles would be made public (TNA/ HS4 – 208) and by 26th March 1944, the Yugoslav Government had levied such pressure Mihailović relented.

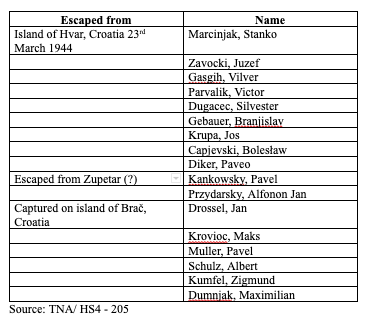

Various PLO’s became involved with exfiltration of conscripted Polish soldiers into the Wehrmacht and set up repatriation centres in a variety of locations throughout the Balkans. On the island of Vis, off the coast of Croatia the following soldiers were waiting for transport to Italy on 19th July 1944 and included non-Poles (TNA/ HS4 – 205). The non-Poles were most likely treated as DP’s (Displaced Persons) and eventually handled through the International Red Cross.

By the end of November 1944, 21 Poles were awaiting evacuation from Split who had been there for some time and requested a speedier response through petitioning the Polish Ambassador to the Vatican to intervene due to the friction between Tito and the Polish Government in Exile. The delay in part was some of the group needed to be interrogated and held in the No. 1 Transit camp for refugees.

In total, some 35,000 conscripted Poles were repatriated and incorporated into II Corps in Italy (Grabowski, 2009).

A small Polish-Russian partisan group (approximately 76 Poles and 17 Russians) was formed out of the liberated Loibl Pass Concentration Camp which was a sub-camp of Mauthausen (Bałuk, 1995). The camps largely contained French nationals. There were two camps to the north and south of the pass and were used by the Universale Hoch- und Tiefbau AG as slave labour from the SS to construct a strategically important tunnel linking Yugoslavia to Austria that eventually would be used to extract Wehrmacht divisions in Yugoslavia.

Albania

SOE operations in Albania was akin to entering a void. During the inter-war years, the FO and SIS placed little value on intelligence gathering since the impoverished country lacked strategic value and they subsequently left a low-key diplomatic presence prior to the Italian invasion (Zidaru, 2020). Foot’s (1990) analysis was brutally short. Missions to northern Albania focussed on local chieftains, notably Abas Kupi, a loyalist to exiled King Zogu and were more anti-communist than anti-Axis or to southern Albanian communist partisans under Enver Hoxha. Part of the complexities facing missions to Albania lay in the dismemberment of Yugoslavia in mid-1941 with western Macedonia and Kosovo being returned to Albania to correct an earlier injustice dating back to 1912 (Hibbert, 2001). The ambivalence, fear of Serbian dominance and dislike of Tito’s grip within the geo-politics of the region added to the woes of the missions since their intelligence was lacking detail in their briefings (Foot, 1990; Hibbert, 2001). The Albanian Section was run by Maj. Cripps and Philip Leake with support from Margaret Hasluck who had resided in Albania, near Elbasan since 1919 prior to expulsion by the Italians in 1939 for espionage (West, 1992).

Albania was annexed by Italy on 7th April 1939 and ‘colonised’ by them. Although the Albanian parliament voted on 12th April to depose King Zogu and unite with Italy, the country was destitute with Mussolini pouring in economic and food aid with the army and civil service being merged with the Italians and in effect becoming a ‘puppet state’. The failure by Britain to protect King Zogu, an anglophile was through appeasement (Petrov, 2002 and 2013) rather than a strategic plan. As a result, King Zogu fled over the border into Greece where he was not welcome and eventually left for Turkey with a large entourage in the hope the Allies would eventually return him to the throne and therefore volunteered his services to the British to no avail (Petrov, 2013).

The missions sent into Albania focussed on attacks on the Italians and the development of a communist backed partisan group with repeated calls for the resistance groups and local chieftains to unite despite their antagonism based on ethnic, cultural, and geo-political beliefs (Hibbert, 2001; Zaugg, 2019). Like Yugoslavia, the lobbying of support for Hoxha came through the deception by Soviet agents working within SOE base at Bari, Italy (Bailey, 2006). It is interesting to note that Kemp (1958) while being briefed for his Albanian operation in Cairo was surprised to see Klugmann occupying a confidential position. Klugmann had been the secretary and inspiration behind the Cambridge University communists and recruited by the NKVD in 1936. Kemp was an acquaintance of Klugmann while studying there and questioned Klugmann’s allegiance.

Polish interests lay in developing courier routes and exfiltration of POW’s, Wehrmacht deserters of Polish origin and forced labourers. With the surrender of Italy in July 1943, it led to the collapse of the Levizja Nacional Çlirimtare (National Liberation Council) that placed difficulties for BLO’s on the ground where civil war and in-fighting blighted operations (Osborn, 2016) with the OSS limiting their efforts too (Haxha, 2017).

SOE’s demand that OSS accepted British line of command further curtailed operations (West, 1992) rather than improve them. Instead, SIS sent 5 operations to circumnavigate difficulties which included:

- TANK 17th November 1943 via motorboat from Italy

- BIRD March 1943 providing reception committee assistance to the other three groups (West, 1992).

An early SOE mission consisted of Flt.Lt. Andy Hands, had been sent to Dibra to contact the local chieftains with a follow up mission STABLES parachuting in Maj. Riddell and Capt. Anthony Simcox to establish the mission there with Hands moving north towards the Kosovo border (Hibbert, 2001). Dibra became the focal point of missions as it was at the epicentre of the resistance group led by Haxhi Lleshi (Hibbert, 2001). Hands and Riddell liaised with Haxhi Lleshi and Fariq Dinë spending much time and effort commuting between Dibra and Peshkopia trying to get the two leaders to cooperate (Hibbert, 2001) to pretty much no avail due to Enver Hoxha having set his sights on a territorial land grab due to the local political vacuum. Dibra, many noted was full of contradictions with the chieftains more concerned over territory than advancing any plans to defeat the Axis.

SOE stepped up operations in late 1943. BLO’s Sandy Glenn and Anthony Quayle (later a distinguished actor) were operating on the coast with limited success (Best, 2021). Kemp (1958) later recalled that Quayle had escaped from the Valona area by sea when his life was in danger, not from the Germans but from the partisans and Balli Kombëtar (National Front) who had pursued and robbed him with attempts on his life and ending up living in a cave.

The CONSENSUS mission took off on 17th April 1943 led by Billy McLean, Capt. David Smiley, Garry Duffy (demolition expert), W/T operator Corporal Williamson and an Albanian Elmaz (interpreter who left the mission and was interned as a result) and landed in northern Greece at Epirus before crossing over the border into Albania with another SOE group led by Brigadier Myers (West, 1992) to meet Hoxha.

Brigadier Edmund (Trotsky) Davies was parachuted into Albania on 15th October 1943 into Benina with the DZ organised by the CONSENSUS team. (Kemp, 1959; Foot, 1990; Bailey, 2006; West, 2019). Included in the drop was Maj. Jim Cheshire, Lt. Frank Trayhorn acting as interpreter and W/T operator and Captain Alan Hare, Sgt. Chisholm, and Bob Melrose. In November 1943 Billy McLean and Capt. David Smiley returned to Cairo via Bari in an MTB (Petrov, 2006; West, 2019) with Smiley returning in April 1944 with Julian Amery (CONSENSUS II).

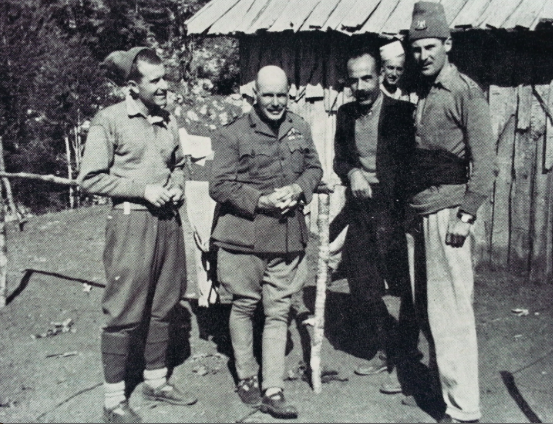

‘Trotsky’ Davies with McLean

Dropped the following night to the same position were two three-man teams to act as liaison officers (BLO). The first team consisted of Maj. Alan Palmer and Capt. Victor Smith and Jock Huxtable the W/T operator (Kemp, 1959; Bailey, 2006). The second team consisted of Capt. Jack Bulman, Lt. Frank Smyth, and W/T operator Harry Button (Bailey, 2006). Dropped with them were canisters containing arms, ammunition, medical supplies, and field office equipment to run a major liaison operation based at Bise. Davies main task in the ill-feted mission was to identify those parties actively engaged in action against the Germans (Kemp, 1959; Foot,1999; Petrov, 2006) and set up an effective communications and supply base for them. Enver Hoxha became the focus of the mission as he led the LNC and appeared to be more active against the Axis than any of the other groups or local chieftains.

Also in the drop party was a Polish Captain Michael Lis or Leon/ Michał Gradowski. Code named ‘Lis’, the Polish for Fox, Michał was an experienced underground operator running couriers from Poland via Budapest as part of the Musketeers resistance group that had links to Britain’s SIS. Led by the charismatic and eccentric inventor/ engineer Stefan Witkowski (Mulley, 2013), the resistance group were highly secretive and potentially posed a threat to Sikorski’s ZWZ/ AK intelligence gathering.

In his obituary, M.R.D. Foot outlined an exceptional war-time career. Educated in Belgium’s Louvain University in agriculture, Gradowski returned to Poland and enrolled in the army and commissioned as a lieutenant in the 24th Cavalry Regiment. Captured by the Soviet forces, he jumped off the train with two other escapers with one shot and the other recaptured. Many of those on the train were murdered at Katyn. Michał escaped to German occupied Warsaw where friends introduced him to SIS through the Musketeers where upon he became engaged in underground activities such as forging and fabricating false seals or courier work to Budapest. As a courier, he smuggled micro-film into Budapest that was destined for Istanbul where he met the reception agent Christine Granville (Krystyna Starbek) (Mulley, 2013). Gradowski was later caught trying to cross into Yugoslavia but escaped again from a moving train. A local priest assisted him, and they conversed in Latin as the only common language. At one point he masqueraded as a Baron and managed to get a flight to Belgrade where he noted strength of the Luftwaffe and ground defences. Through impersonating himself as a Baron Ostrog of Estonian origin, his forged papers were so good he managed to persuade a German Consul to give him a lift to Istanbul (Mulley, 2013) where he met SOE Station chief Gardyne de Chastelain who recruited him into the organisation.

Christine met Michał in Cairo having been shipped there for training. Michał was to be trained as a Cichociemni or Silent and Unseen (special forces) despite a knee injury. First in Cairo and then Mount Carmel in Palestine (badge number 0288/1600, Lieutenant, Special Section C-in-C General Staff, parachuted on orders Minister of National Defence) (Anon, 1993) he completed the training. Mount Carmel was an SOE training centre in a monastery near Haifa and was designated STS102/ ME102 where parachute jumps and completion of other SOE courses such as radio and ciphers took place to meet demand for operatives in regional theatres of war which included Slovenia, Hungary, Yugoslavia, and Albania. The Haganah who were to be infiltrated into Hungary (Bauer, 1966; Bajc, 2002) also were trained at Mount Carmel. Michał was parachuted into Albania in operation WORKROOM (Maresch, 2005) on 10th October near lake Ohrid on the border of Albania and Macedonia. His prime task was to set up escape routes for Polish POWs and those conscripted into the Wehrmacht. This part of the operation was not successful, so Michał joined operation STEPMOTHER.

Kemp’s operation (STEPMOTHER) lasted 10 months in Albania. Flown from Darna in northeast Libya on 10th August 1943, the team consisted of Sgt Allcott (RAF), and W/T operator Cpl Roberts who had been parachuted in a month earlier. Two Halifaxs’ carried four missions together: SCULPTOR led by Major Tilman, SAPLING led by Maj. Gerry Field and Maj. George Seymour leading the SCONCE mission. They were to be dropped together to meet McLean and Smiley at the village of Shtyllë in the mountains about ten miles southwest from Korçë (Kemp, 1958). The mission was frustrated due to the lack of cooperation by the partisans. This was highlighted when a planned attack on a German convoy being cancelled at the last moment by brigade commander Mehmet Shehu who, despite having 800 men did not want to risk exposure to a German outpost nearby. Kemp had a low opinion of the communists whose behaviour seemed focused on rival partisan groups rather than attacking Germans and sabotage operations. Betrayed after trekking through Kosovo in difficult conditions, it took several months to extract him, and the final straw was accusation of endangering the partisans in Montenegro.

Capt. Michael Lis joined Riddell and Kemp as an extra BLO (Kemp,1958) whose group had an established camp made up of huts and camouflaged tents in the mountains. They had regular patrols and sabotage actions taking place in the vicinity (Bailey, 2009). Dibra, the partisan HQ for Haxhi Lleshi that had been held since the Italian armistice came under intensive attack on 7th November (Kemp, 1958; Hibbert, 2001; Bailey, 2009). British missions at Peza and Biza had been destroyed with a few survivors making their way to Dibra that took several days due to the intensity of the action by German 3rd Brigade. They had to pass through the Marantesh hills in appalling conditions with a mule train of 60 animals laden with kit (Bailey, 2009). Lis reappeared on 20th November at the camp in Martanesh while Riddell, Kemp and Gregson-Allcott fled to the hills and on the run from further German anti-partisan action. Lis had lost all his kit during the escape from Dibra (Bailey, 2009). It is through Michał’s citation for the Military Medal we understand what happened at Dibra (TNA/ PRO WO373/184/25). On 16th November 1943 Michał gallantly decided to remain as the BLO in a forward position with the Albania partisans. Under constant fire and shelling, he withdrew when the rear-guard had been broken and they managed to escape into the foothills. Kemp with Gregson-Allcott and their translator, Tomaso collected their mules and kit and left Dibra for Pesshkopijë on Riddell’s suggestion to save their mission (Kemp, 1958). A planned counterattack further east would prevent Xhem Gostivari’s (Macedonian warlord allied to the Germans and Italians) retreat (Kemp, 1958). However, the Germans beat them to Pesshkopijë and needed to move to the new HQ at Sllovë where they would find Michał. Haxhi Lleshi withdrew the remnants of his force and crossed the river Drin to join Enver Hoxha’s forces (Kemp, 1958; Hibbert, 2001; Bailey, 2009).

Trotsky Davies was eventually forced to abandon his camp at Biza, after being perused by the Germans, dumping all equipment and supplies with the partisans. His guards absconding (Kemp, 1958) leaving starving frost-bitten men to fend for themselves. Ambushed on 8th January 1944 by hostile Albanians, Davies was wounded and captured along with two officers. Nicholls and Hare managed to escape and trek south (Kemp, 1958). At the same time Enver Hoxha’s partisans fled the Cermenlikë massive and trekked south (Kemp, 1958; Hibbert, 2001; Bailey, 2009).

The winter in Albania was harsh with the British missions under constant anti-partisan operations, threatened with potential betrayal and lack of re-supply that put many teams close to starvation and illness of which Michał succumbed. Some of the remaining teams made for Xibër. Mclean stepped in and reviewed all their missions, concluding that the poor state and health conditions required evacuation for most of the SOE personnel as this would pose a risk to the others (Bailey, 2009).

In January 1944, Riddell set out to find the survivors of Davies mission and found John Davis and Gregson-Allcott had been on the run for the bulk of the winter dodging anti-partisan patrols and hid with Albanian families or in shepherd’s huts. Riddell arranged a drop at Dega, the first since November 1943 with most of the supplies pilfered by the local population. In February, Riddell found Michał who had been in hiding with the Lita family (Bailey, 2009) and in poor health.

On 28th March 1944 three Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 medium bombers landed at Berane to take Kemp back to Bari (Kemp, 1959). Michał along with Cooper, Gregson-Allcott and Chisolm were flown out of Berane in July with those fit for duty joining McLean’s mission (Bailey, 2009). Michał prior to demob in 1947 was thought to be tracking down war criminals in Germany and eventually settled to a civilian life in France.

Greece

The invasion of Greece by the Italians acted as the catalyst for setting up a communications and intelligence cell in the autumn of 1940 supported by Polish VI Bureau and Gen. Kazimierz Sosnkowski (Przewoźnik, 2005). The cell Grzegorz was the responsibility of Col. Alfred Krajewski (Adam Korab) in Athens despite the Polish envoy Władysław Schwarzburg-Günther opposing the plan. Grzegorz worked in conjunction with Istanbul (Bey), Sława in Belgrade and Romek in Budapest. Col. Alfred Krajewski was assisted by II Bureau and SIS with some support from the Greeks in setting up and maintaining the communications network (Przewoźnik, 2005). The internal conflict between II and VI Bureau hampered the effectiveness of the cell resulting in it being withdrawn in April 1941 with little achieved. Although there were further proposals for re-establishing a cell in Athens, the events in this theatre of war overtook any further development.

While the Poles lost a valuable communications and courier routes through Greece, SOE lacked the research and resources to develop a strategy in dealing with the conflicts between the partisan groups EAM, ELAS and the KKE (Petrov,2009), leaving agents and BLO’s exposed (Ogden, 2010). An inactive untrustful partisan army (Foot, 1990) threatened both operations and developing a strategy for the country. The invasion of Greece had taken SOE by surprise and the unimaginative field agents hampered effective operations (Foot, 1999). The muddled approach saw SOE associate itself with the left and SIS concentrate on utilising connections through Greek intelligence and monarchists that amplified British internal conflicts in Cairo (West, 2019). SOE operations focused on relatively small sabotage and demolitions or on communications on the mainland whereas the flotilla operations in Crete achieved much more. The muddle in Greece impacted upon post war conflict and the CIA’s operations for decades (West, 2019).

However, Station ‘T’ based in Jerusalem worked with one of the most famous allied agents, Capt. Jerzy Iwanow-Szajnowicz (Ciechanowski, 2005) (Athos) whose exploits would be challenging to believe in fiction. Resident in Greece since 1925, he was educated in Belgium and France and brought up by his Polish mother. A gifted athlete and swimmer who had represented Greece, he had returned to Greece due to the outbreak of war to organize the evacuation of refugees and soldiers through Thessalonica.

In 1940 he was recruited by Capt. Tadeusz Zdzisław Szefer (Kościelny) who was based in II Bureau in Athens, and both were evacuated to Palestine on SS Warsaw (Anon, n.d). Station T recognised his value due to his ability to speak 6 foreign languages and planned to return him to Greece (Anon, n.d). Although he initially joined the Carpathian Rifle Brigade, he undertook specialist training at the behest of SIS who had recruited him at the end of May 1941 (Ciechanowski, 2000; Anon, n.d). On 21st October 1941 he was returned to Salonika aboard the British submarine Thunderbolt captained by Lt. Commander Cecil Crouch (Anon, n.d). He was tasked to carry out intelligence gathering on shipping at Piraeus and the airbase at Attica, setting up W/T communications and sabotage. He conducted reconnaissance of the German fortifications at Marathon and through the Nation Rebirth Organization (OAG) set up an extensive network of agents (Anon, n.d).

Capt. Jerzy Iwanow-Szajnowicz also inspired a breath-taking raid on the Malziniotti factory based in New Faleron (Ciechanowski, 2005) without a shot being fired. The sabotage in the Malziniotti factory was carried out by adding an oil destroying substance to aero engines causing new and serviced engines to seize up during flight (Anon, n.d). As a champion swimmer, he used his skills to lay limpet mines on a German submarine (U-133) and the Destroyer Hermes (Ciechanowski, 2000; Day, 2022; Anon, n.d) which were sunk off the coast of Attica. Other exploits include diversionary raids and destruction of fuel dumps on airfields at Chasani, Eleusis, Tatoi and Patras (Day, 2022; Anon, n.d). It is thought he may also have been responsible for the sinking of 6 more vessels that mysteriously disappeared in Greek waters (Anon, n.d). With a price on his head and the inability for SIS to evacuate him, Jerzy attempted to escape to Turkey. Betrayed and imprisoned in Averoff, he was shot on 16th December 1942 while attempting to escape from the execution site at Kessariani. (Ciechanowski, 2005). Caught with him were the Gianatos and Kontopoulos families who were tortured by the Gestapo and sentenced to death.

British intelligence was aware of a high number of Polish escapees stuck in Greece. The Wehrmacht had a significant number of conscripted Poles within their ranks who could be used to start a revolt against the Germans which had been discussed within SOE (TNA/ HS4 – 209).. Polish Liaison Officers (PLO’s) were sent initially to Athens and then to major islands or into the hills where some Poles were with Andarte (partisan) bands (TNA HS4 – 206). Estimates of Poles in Greece ranged from a few hundred to 25,000 that would cause operational and logistical headaches for Polish-British Missions and Force 133. Only 7,000 were in Greece at various locations due to the Wehrmacht withdrawals of troops to Italy and France in August to September 1944 (TNA/ HS4 – 206). Mass desertions were not to be encouraged through propaganda due to lack of transport facilities despite a Polish BBC announcement (TNA/ HS4 – 205). Another difficulty was ELAS hostility towards conscripted Poles that might place them in personal danger, making the role of the PLO’s more difficult (TNA/ HS4 – 209) and the constantly shifting politics surrounding ELAS (TNA/ HS4 – 205).

It was also known there were 4,300 Poles remaining in Romania of which 1,100 were of military age with some Polish government employees numbering between 30 to 60 that would require the Anglo-Soviet Committee to release them and a need for a PLO to assist, however, those who were politically sensitive to the Soviets were to keep a low profile for later evacuation (TNA/ HS4 – 206). This demonstrates that as the Germans evacuated the Balkans, the influence of the Soviets would make each evacuation more complex due to the local political circumstances.

Capt. Buryn would lead the Polish mission to Greece from his office in Cairo. ‘Outposts’ had been set up in different locations by the Polish VI Bureau based in Bari to process the various Polish conscripts: Palaia-Yannitsou, Italy; Goura, Corinthia, Greece; and Tsouka, Phthiotis, Greece. Staffed by Poles, their role in the repatriation and debriefing process was essential in the repatriation process and had full British Foreign Office and War Office approval and given priority.

On Leros, (Operation DODECANESE/ RUBICON) the Wehrmacht garrison was approximately 5,500 with 800 conscripted Poles with a high level of desertion in the Zerwasi area that needed an immediate evacuation from Pireus due to the low morale of the conscripts and had reportedly resorted to eating dogs. Other locations included Attica with several hundred needing evacuation, 600 on Rhodes (who wanted to attack the Germans), 200 at Yannena (Ioannina), 40 from Corfu and 10 from Crete. Three Poles were selected to be infiltrated into Greece and act as PLO’s. 2nd Lt. Stanisław Lukas (Capt. Long) mission to Crete to outpost “Stranger” between 11th to 12th September 1944 and returned on 12th March 1945 working with Force 133 (SOE Section covering the Balkans). On arrival, Crete had almost been completely evacuated by the Germans and his work on repatriation of conscripted Poles into the Wehrmacht was limited, however managed to after exfiltrating 200 Poles from Chania and several hundred from Attica (TNA/ HS4 – 206; TNA/ HS9 – 948 – 5). Such was the volume, SOE requested Capt. Long (Lukas) be released from Polish VI Bureau duties and support the evacuations from Chania.

Operation EDES ran from 16th September until 13th December 1944 (TNA/ HS4-207). An LAC dropped Capt. Makowski (Benn, Andrzj 2, Tomek 2,) onto a beach somewhere along the coast of Kastrosykia. On the beach were 70 German POWs and 8 conscripted Polish Wehrmacht deserters awaiting collection who were then sent to M.E 48 in Italy. Makowski was sent to the Paramythia Mission with Lt. Sisley and US Capt. A. Rogers (OSS) probably to investigate the massacre that took place between 19th and 29th September in 1943. Although there were several deserters in Louros, to the south, Col. Tom Barnes requested they went to liaise with Col. Zervas’s 10th Andartes Division. The Germans had withdrawn from Paramythia area along with Corfu, Igoumenitsa, Ioannina and Preveza. His mission was to search for Poles conscripted into the Wehrmacht and planned to repatriate them into Ander’s Army (TNA/ HS4 - 206) through the repatriation centre in Salonika that celebrated liberation on 2nd November 1944. Other repatriation centres were set up at Athens and Patras for transfers to Italy. Retraining would take place in Palestine after being interrogated at M.I.C (Maardi Interrogation Centre) in Cairo. By October 1944, Makowski was posted to Corfu after suffering from Malaria. He was evacuated to Cairo on 12th December and arrived on 18th December 1944. Some 700 Poles were incorporated into the Polish II Corps with a further 400 still with the Wehrmacht on Crete, Kos and Leros. A further 200 were blocked by the Greek authorities with Capt. Soyker in Athens legation seeking their release (TNA/ HS4-207).

Operation SPEARHEAD 1 was planned in August 1943 (TNA-HS4/141) to insert a Polish officer (PLO) to initially join WORKROOM 2 team to interrogate and vet Polish deserters from the Wehrmacht that included those who were now operating with the resistance (Link: Polish Intelligence/Continental Action).

Their duties would include intelligence gathering and if recruited enough soldiers would be directed towards sabotage, propaganda operations and recruitment of Poles from Todt organisation to bolster numbers. There were on-going concerns within the British ‘circles’ about the nature of these operations and their relationships within the Polish apparatus of VI Bureau (DAY) and the Ministry of Interior (NIGHT) that needed reassurance from Col. Mercik (SUN) who coordinated Polish operations from Cairo that the operation was viable.

In Operation SPEARHEAD II, Lt. Stanisław Hołły (Capt. Kula), an infantry officer and Cichociemni, was parachuted into Kastania in southern Greece 13th September 1943 on an intelligence operation with Lt. Col. James (Hamish) Torrance, a highly accomplished field operator. Initially, Kula was working with British NCO’s at Bertuli and sent to the post at Larissa where he was working alongside Makowski until October 1944 where he was recruiting TODT deserters and escaped POWs. While there, he was informed that there were 28 Poles with the ELAS “Battalion of Death” based at Makrakomi just over 120Km away. ELAS refused to allow Kula to negotiate their release and returned to Karpenissi where the BLOs were based. Unknown to Kula, the Poles based with ELAS were asked to join in the Greek Civil War against EDES which they refused and were disarmed. Although they intended to join Kulas, ELAS gave them three alternatives: evacuation to Serbia, interned in Greece for the duration of the war or fight. They escaped and joined the BLOs mission. The report was compiled by Władysław Malankowski (TNA/ HS4 -208) and resulted in British operations and policy changes to evacuate all Poles as soon as possible since there was a real threat of being killed. Negotiations with ELAS resulted in evacuations progressing with completion by mid-March 1944.

Kula himself had temporarily been arrested at Gardiki by ELAS and disarmed. On his release made his way to Marmara on a special mission with the BLOs before marching through various ELAS strongholds to Veneto where he was picked up by a caique on 25th December 1943 and taken to Smyrna. Here, he took a train to Aleppo and then flew to Cairo landing on 3rd January 1944 (TNA/ HS4 – 208). Evacuated with Kula was a Polish Jew Aleksander Queller who had been part of Palestine contingent and caught by the Germans. As an escapee, Queller had distinguished himself as an interpreter speaking fluent Greek and was recommended for posting to Force 133 who had a policy not to recruit Jews (TNA/ HS4 – 208).

The volume of repatriations of Poles through Athens required an additional PLO Capt. Kes (Lt. Gerhard Sykora a.k.a Sanders) to command the operation from the end of October 1944 and his duties included the setting up another ‘outpost’ at Patras. His mission was completed 31st December 1944 with evacuation in January 1945.

On 25th to 26th October 1944 2nd Lt. Antoni Zaleski (Capt. Anthony Glen/ Giewont 2, Sten) an infantry officer, was landed at an unknown destination in Greece and involved in rounding up Polish conscripts into the Wehrmacht on behalf of Force 133 (TNA/ HS4 – 206) and developing a courier route to Bulgaria. By end of October 1944, he was sent to assist the PLO based in Yannena (Ioannina) due to the volume of Poles still needing to be processed. He returned to Cairo on 9th December 1944.

Lt. Tomasz Kurasiewicz ran an intelligence reconnaissance and propaganda mission. Little is recorded of his mission.

2nd Lt. Jerzy Lissowski (Capt. Fox), an infantry officer, landed 25th October 1944 to organize courier routes and assist with repatriation of Poles around Salonika.

Lt. Jerzy Skolimowski (Capt. George Deen; George Skolly), an artillery officer, landed 14th September 1944 for intelligence operation, distribution of propaganda and sabotage on Crete (TNA/ HS4 – 205). By the middle of November 1944, the arrival of PLOs in Greece encouraged Poles held by Greek guerrillas (ELAS) to escape which raised objections to PLO’s presence in the vicinity which was meted out on Skolimowski (TNA/ HS4 – 207) when ELAS refused to allow any to be repatriated. By October 1944, Skolimowski was in Lamia, in central Greece and reported the retreating Germans were blocking civilian traffic through the lines. He had noticed many ships were returning to Alexandria from Piraeus empty and suggested these were used to transport the Poles rather than back to Italy. He returned to Cairo on 9th December 1944.

Lt. Jerzy Waletko (Bart) landed 5th to 6th May 1944 recruitment of conscripts and TODT organisation workers and was active in the Trikala area in north-western Thessaly in October 1944. He was in contact with the 7th Andartes Brigade and liaised with ELAS to release Poles operating with them which was refused. He operated in the mountainous area around Triklino in N.W Greece and was also in contact with the A.M.M in Kardista in western Thessaly where he was blocked form contacting Poles directly and had to negotiate through an intermediary which proved both difficult and showed few results. However, desertions from the 104th German Division with 15 Poles evacuated from Agrinio, 25 from Arta and Preveza and 50 individuals from the ‘outpost’ at EDES H.Q.

Capt. Lake (2nd Lt. Szantyr) would work around POW camps in liberated areas in October 1944 and was posted to liaise with Greeks in Athens to improve the process for the Poles to be released whose role was no longer needed by early November 1944.

By the end of October 1944, SOE felt their role in Greece was concluded and that all the PLO’s should return to H.Q. 3 Corps (3rd Carpathian Rifle Division) in Cairo to await further instruction as Force 133 no longer required them while the UNRAA led by an American Mr Gerstensang, would make their facilities available to the evacuation and housing of Poles (TNA/ HS4 – 206). The total number of Poles evacuated were by 12th January 1945:

- Poles arrived in Italy (Bari) - 700

- Poles in Greece obstructed by ELAS - 200

- As POWs in Wehrmacht in Crete - 200

- As POWs in Wehrmacht in Kos/ Leros - 200

Capt. Sykora was highly commended in his role in managing the evacuations from Greece (TNA/ HS4 – 207) and married to an Egyptian Nelly Kahil before returning to Britain for demobilisation. His operations in Greece were held in high praise by SOE.

Romania

During the inter-war years Poland had supplied Romania with arms and aircraft and geopolitically mutually supported each other (Hrenciuc, 2007). With the rapid collapse of the September campaign by the surprise Soviet intervention (Kochanski, 2012; Zidaru, 2015) Rydz-Smigley decided the Romanian Bridgehead was untenable and ordered all units east of the Vistula withdraw into Hungary and Romania who were neutral at this stage with the view to reforming on French soil (Zaloga and Madaj, 1991). On 17th September the Polish president, Ignacy Mościcki and his entourage crossed into Romania with a safe passage to the port of Constanța (Kochanski, 2012). Britain and France made little effort to persuade the Romanians to release Polish personnel of whom some were interned in appalling camps. It was estimated that 30,000 Polish soldiers and airmen were interned in Romania and a further 40,000 in Hungary with smaller numbers in Lithuania (13,800) and Latvia (1,300) (Zaloga and Madaj, 1991; Kochanski, 2012). Displaced civilians in Romania were around 10,000 in 36 provincial centres (Kochanski, 2012) who eventually fled to Hungary or the Middle East with a small number returning to Poland after the war (Majewski, 2017). Marshal Edward Rydz-Smigley, the Commander in Chief, was interned at Dragoslavele until his escape to Budapest under a false name.

In early December 1939, the decision to set up Station R (Roman) headed by Lt. Col. Tadeusz Skinder as part of ‘Action South’ (Dubicki, 2005) for trusted and secure communications with Poland. Based in Bucharest and subordinate to II Bureau, it had several section operating there: Intelligence led by Maj. Joźef Bińkowski; Counterintelligence: Maj. Stanisław Kuniczak and general duties by Capt. Stefan Konarski (Dubicki, 2005). A secret liaison team led by Lt. Col. Ludwik Sadowski worked closely with Romania intelligence and possibly responsible for sabotage. Linked to Station R was ‘Stasia’ and ‘Cezar’ based Černovcy in the Ukraine linked to the AK GHQ based in Lwów with some 50 couriers regularly crossing the borders (Dubicki, 2005). R Station was a vital link between the AK, London, and SIS for communication and the need for the SIS to have a good understanding of Romania’s political, economic, and military strength.

The Station worked closely with British Military Intelligence (MIR) when Capt. Hazell and Capt. Burland were transferred to SOE who assisted in the smuggling of arms, W/T sets and nitroglycerine into Poland from Romania and military intelligence personnel via the network used by couriers (Dubicki, 2005). A major sabotage plan was devised to block the Danube to disrupt fuel supplies to Germany by sinking chain-linked barges across the river (Dubicki, 2005; Ogden, 2010).SOE, SIS and the Poles in Hungary

The development of the Station was thwarted in November 1940 when an anti-Allied and pro-German policy enacted by the Iron Guards and Gen. Antonescu discovered the extent of Polish activities on their soil which meant a secret evacuation took place. It was not until mid-1941 that Capt. Bolesław Ziemiański, an experienced intelligence operative re-established a network, assisted by Henryk Jagiełło and Mieczysław Karpiński both formerly of counterintelligence and were able to draw upon the large Polish diaspora in Romania (Dubicki, 2005) for assistance. While operations to sabotage the lock gates and shipping in the Iron Gates through mining the river caused some damage, the disruption was more minimal due to insufficient use of explosives. Operation HUSH HUSH was another attempt by the Allies to use an old freighter the SS Mardinian, Panamanian flagged, carrying Royal Marines and manned by the Royal Australian Navy on a ‘one way mission’ to sabotage the Iron gates also resulted in failure when the ship was detained by the Romanian Customs and all the arms and munitions confiscated at Giurgiu (Ogden, 2010; Fazio, n.d).

Freight traffic was monitored with some accuracy since a Pole based in Bukovina, Maksymilian Osman managed to gain employment with DDSG, an Austrian owned Danubian shipping line who regularly reported on military, equipment, and oil shipments. Ziemiański’s network was supported by a second network between 1941 and the autumn 1943. Capt. Bronisław Eliaszewicz (Bruno Ortwin) ran cell Tandra, and the second cell was Tulsa under Capt. Ziemiański. Eliaszewicz who operated under the guise of a Japanese Military Attaché that was later penetrated by Romanian Intelligence and the Gestapo. The quality of the intelligence gathered and the range covering German and Romanian army units, state of airfields, the strength of anti-aircraft batteries at the Ploiești and oils shipments was deeply appreciated by SOE and SIS (Dubicki, 2000). Despite the arrests, operatives managed to deliver important intelligence to Istanbul up until 8th January 1944.

The Poles and SOE saw an opportunity to destabilise the Axis while the Germans were placing greater pressure on Marshall Antonescu over greater commitment to the eastern front through commitment of 600,000 men and further suppression of opposing political parties from 1942. The Poles continued to produce quality intelligence that included Black Sea defences and the initial peace talks between the Soviets and the Romanians. On 23rd August 1944 the coup d’etat led by King Michael 1, accepted ceasing of all hostilities against the Allies. The Soviets already occupied Moldovia and used the power vacuum to occupy the rest of Romania as a hostile state. The armistice signed on 12th September 1944 was on Soviet terms that resulted in 160,000 Romanian soldiers being deported to Russia.

Operation AUTONOMOUS impacted on Polish operations that enabled some personnel to be withdrawn to Italy, however Ziemiański’s team was arrested by the Soviets and imprisoned in Warsaw while Capt. Bronisław Eliaszewicz and Capt. Bogusław Horodyński were deported to the USSR gulags (Dubicki, 2005). Col. Wiesner of the British Mission sought to help evacuate remaining Poles to Italy, however the Soviets requested a report on their activities before assistance would be granted and with the arrest of Ziemiański, the remaining team were compromised. Operation YARDARM was the symbolic ending of operations in Romania (Bennett, 2005).

SOE

After the Legionnaire’s rebellion and the installation of pro-Axis Marshall Ion Antonescu between 21-23 January 1941, the SOE mission in Bucharest had largely escaped with the diplomatic mission. Although there was some limited radio contact through a W/T set left in Prince Stirbey’s house (he was the father -in-law of Eddie Boxshall, ran SOE’s desk in London), the main resistance contact was Luliu Maniu, head of the Peasants Party (Foot,1990; Haynes, 2019; West, 2019; Zidaru, 2020b) who turned out to find difficulties with any proposed activities (Foot, 1990). Indeed, Foot’s analysis of the Romanian section indicates the internal struggles within SOE in Cairo and then Bari making operations ineffective.

RANJI was led by Maj. David Russel with W/T operator Nicolae Turcanu and dropped into Romania on 15th June 1943 to set up communication links with Maniu. Russel was reported to have been murdered for his gold coins (Zidaru, 2020a). On 9th November Maniu requested a special delegate to be allowed to leave Romania due to political changes that was granted after London had contacted the Soviets and the Americans that accelerated the need for AUTONOMOUS (Zidaru, 2020a).

AUTONOMOUS led by Gardyne de Chastelain (former head of SOE in Istanbul) on 22nd November 1943 was aborted when the Liberator failed to find the DZ in Albania and lost signals while running out of fuel over the Adriatic (West, 2019). The second attempt on 21/ 22 December 1943 failed when the team were arrested by local gendarmes before they could meet up with RANJI (Ogden, 2010; West, 2019; Zidaru, 2020a). The team was transferred to the Abwehr in Bucharest and used in propaganda to embarrass the British since the storyline was the team were sent to negotiate a separate peace with Marshall Antonescu thus annoying the Soviets at the same time (West, 2019; Zidaru, 2020a).

Political complexity developed further when Prince Barbu Stirby arrived in Cairo to secretly negotiate an armistice (West, 2019) and the Iasi-Chisinau Soviet offensive on 22-30 August 1944 to break into Bessarabia put greater pressure on Romania to break away from the Axis powers (Zidaru, 2020a and 2020b) The failed coup d’etat on 23rd August 1944 by King Mihai I and the Soviets defeat of the German and Romanian armies was a drastic blow that can be compared to the German defeat at Stalingrad. With over 1m Soviets marching eastwards and onto Bucharest, the British invasion of Romania through Greece became less likely since the Allies had already secretly agreed Romania would be in the Soviet sphere of influence which meant SOE lost interest in further operations (Zidaru, 2020a).

| Organisation(s) |

Operation Name or Operatives |

Personnel |

Aim/Activity of Operation |

| SIS

MI (R)

Section D

Subversion and propaganda

|

|

Lt. Col. William Harris-Burland OBE

Capt. Max Despard DSO, RN

Major W.R. Young (D Section)

Hon. Col. George Taylor, CBE

John Toyne

Treachy

Anderson

|

Sabotage |

| SOE Missions |

RANJI

AUTONOMOUS |

Capt. David Russel MC,

W/T Op. Nicolae

Țurcanu (Reginald)

St. Maj. Petre Mihai

Reception at Homolje (Serbia):

Lt. Col. Jasper Rootham

Lt. ‘Mickey’ Hargraves

W/T Op. Sgt. C.E. Hall

Lt. Col. ‘Chas’ de Chastelain, DSO, OBE

Maj. Ivor Porter

Maj. Charles Maydwell (withdrawn)

Capt. Silviu Metianu

|

To contact Agent Section D Luliu Maniu

Russel was murdered for gold coins he was carrying on 4th September 1943 leaving Nicolae

Țurcanu to complete the mission and prepare for AUTONOMOUS. |

| M19 |

MANTILLA (1943)

GOULASH (May 1944)

SCHNITZEL (June 1944)

RAVIOLI

DOINER

|

Sgt. Isaac Macarescu

Sgt. Levy (Raico) Depesco

Shaika Trachtenberg

Isaac Ben Ephraim

Sarah Braverman

|

See Operation AMSTERDAM:

Goulash was a 2-man MI9 team dropped near Craiova in Romania 2-3 May to rescue 300 British and US airmen and assist local Jews. Captured next day that triggered Schnitzel 3-4 June and followed up by Ravioli 30-31st July. These teams reached Bucharest to liaise with the Jewish Agency.

Operation Doiner was in August and caused a significant diplomatic stress point. The operation continued to enable the Palestine Office to issue identity papers and transit permits to Palestine for Jewish refugees from Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia much to the irritation of Molotov that strained Soviet relations with Marshall Antonescu and Maniu and SOE’s incursion into Foreign Office Affairs. It could also be described as one of the earliest Cold War incidents.

|

Sources: Ogden, 2010; West, 2019.

Turkey

Turkey’s neutrality was a convenient ‘highway’ for intelligence exchanges and movement of missions, refugees and escaped military personnel. Istanbul has been described as the ‘Intelligence Capital’ (Bennett, 2005) with most consulates and delegations engaged in intelligence. Polish Intelligence had been operating prior to the war (Ciechanowski and Dubicki, 2005). The Poles recognized that SIS and Turkish Intelligence were closely co-operating and would be more productive than their own (Bennett, 2005) until the arrival of Col. Sadowski in November 1943 whose role was to co-ordinate all Polish networks in Turkey. Intelligence cell No.3 and others in Istanbul was under the control of Station ‘T’ in Jerusalem from the summer of 1940 and initially led by Capt. Jerzy Fryzendorf of II Bureau (Kresowiak) with subsequent numerous changes in leadership. One of the notable successes of Cell. No. 3 was to decipher codes sent from the German Consulate (Ciechanowski and Dubicki, 2005).

An independent Station Bałk was set up under Maj. Piechowiak to counter German activities in the infiltration of former Poles into the armed services or masquerading as members of underground armies to commit sabotage disguised as escapees (Ciechanowski and Dubicki, 2005). Through this route the following agents were identified after interrogation and checking with the AK in Warsaw and London: Ryszard Mączyński, Tadeusz Dębnicki, Bronisław Biernacki, Mieczsław Bratkowski, Stanisław Swedkowicz, and Jan van der Linde (Ciechanowski and Dubicki, 2005). In the case of Jan van der Linde, he was not of Dutch origin and claimed he worked for “Miecz i Pług” (Sword and the Plough). Unfortunately, while serving in Warsaw as Hans Merz had arrested Col. Janusz Albrecht, the AK Chief of Staff and was known to the AK and later SOE (Ciechanowski and Dubicki, 2005).

Italy

E/ UP and VI Bureau’s operations were not just confined to the Balkans or felucca operations operating out of Gibraltar. SOE operations in Italy after the invasion of the mainland in September 1943 became entangled with the internal crisis between the Italian Communists and partisan groups such as the Justice and Liberty Brigade in northern Italy. SOE operations fell into three main categories: guerrilla attacks on the German and Fascist Italian personnel and supply lines.