Operation WACHLARZ

(Operation FAN)

Introduction:

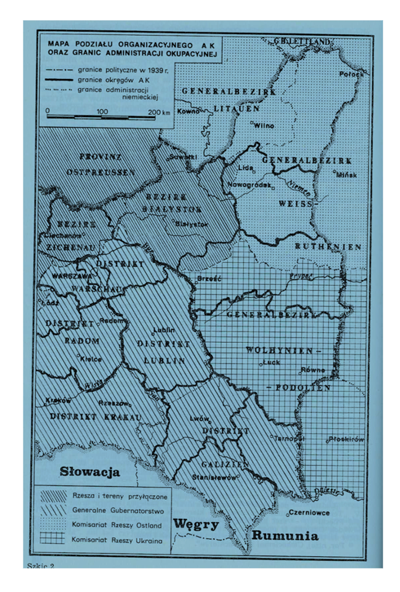

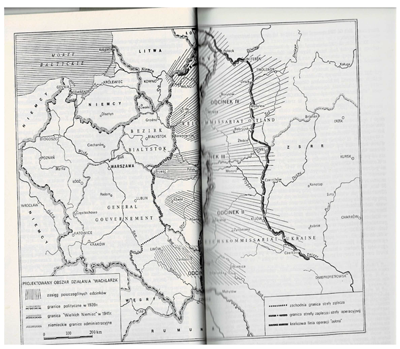

It would be wrong to assume that on the defeat of Poland with its partition between the Reich and the Soviets, the country would be subdued and subservient to the occupiers. After the Germans launched their attack on the Soviets in Operation BARBAROSSA, a mixture of Polish underground units started their offensive of sabotage and diversionary attacks on supply columns (Williams, 2012). At this stage of the war, the Polish underground movement was fragmented and worked alongside political parties that meant the Union of Revenge and Wachlarz operated semi independently until the Home Army or Armia Krajowa brought them together under the Directorate of Diversion (Kedyw) and a more unified movement. The Polish sabotage campaign behind the German front in Russia is often overlooked and was spread-out as a ‘fan shape’ from Warsaw to the Baltic Coast and the Black Sea. This was to the east of the 1939 border or from the banks of the river Dvina to the Dnieper (Garliński, 1969; Chlebowski, 1985; Bałuk, 1995).

The operation:

Although the Wachlarz operation was known to SOE (called the ‘Big Scheme’ by SOE), they initially operated with a degree of independence as part of the ZWZ. In the autumn of 1941, the ZWZ command established a diversion unit that was the forerunner of a planned larger uprising. The C-in-C of the ZWZ, Gen. Stefan Rowecki, gave a twelve-point response to the plan outlining the agreed operational areas, its secrecy within the ZWZ, the need not to overlap with other operations and that recruitment and financing would be separate from the ZWZ (Chlebowski, 1985). Sent to areas behind the German divisions, they were tasked in sabotage and use diversionary actions targeting bridges and rail communication networks (Chlebowski, 1985; Bałuk, 1995). The unit was initially commanded by Maj. Jan Włodarkiewicz (Damian) who was killed in mysterious circumstances in Lwów on 18th March 1942 and then succeeded by Maj. Adam Remigiusz Grocholski (Doktor, Brochwicz, Miś, Inżynier, Waligóra) (Bałuk, 1995) from April 1942 until March 1943. The Wachlarz was divided geographically by areas under German occupation with orders emanating from Warsaw and areas under Soviet occupation was commanded by Gen. Michał Tokarzewski-Karaszewicz before operation BARBAROSSA which was launched on 22nd June 1941.

Initially, the period from September 1941 to April 1942 was focussed on recruitment, training in subversion skills and establishing routes behind the rear lines of the Wehrmacht. The integration into local communities with false names and alibies and develop arms dumps and caches were prioritised too. Integration into the local population was perilous since the regions had restrictions on movement and employment with all the local population having to register their whereabouts to local Reich administrators. Certain areas were forbidden to enter. However, during the winter of 1941/ 42, German companies and the Todt Organisation needed labour to fill the employment void and began to recruit locally (Chlebowski, 1985) which enabled the Wachlarz units to infiltrate both the organisations and various barred regions. During this period, the Eastern Front stretched from the outskirts of Leningrad and the Oblast, south towards the outskirts of Moscow, Taganrog on the Azov Sea and the Crimea.

The second phase which ended in May 1942 was a trial period of moving the first teams or patrols of the Wachlarz into strategic and forward positions, particularly the bridges over the Dvina and Dnieper and other key communications in readiness for sabotage operations to commence to damage the extended supply lines. General Stefan Rowecki issued a five-point plan:

- Contribute to the destruction of the material strength of the Germans

- Contribute to the hindering of the provisioning of the (eastern) front by the Germans

- Guerilla warfare in the rear of the Germans

- Delay the approach of the Soviets

- Start join actions with Polish Ukrainians

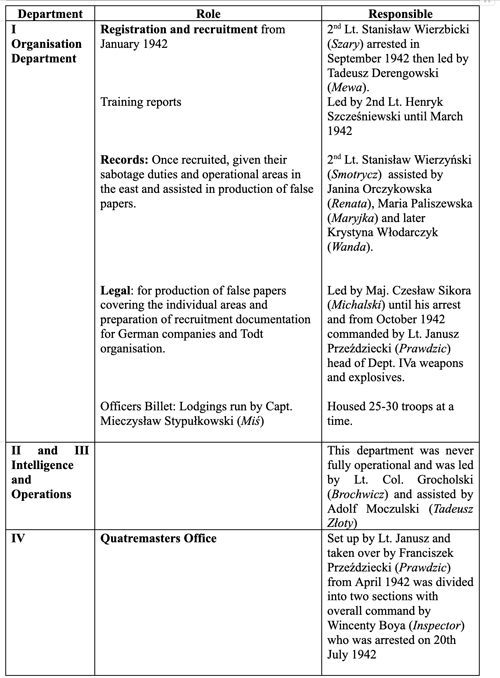

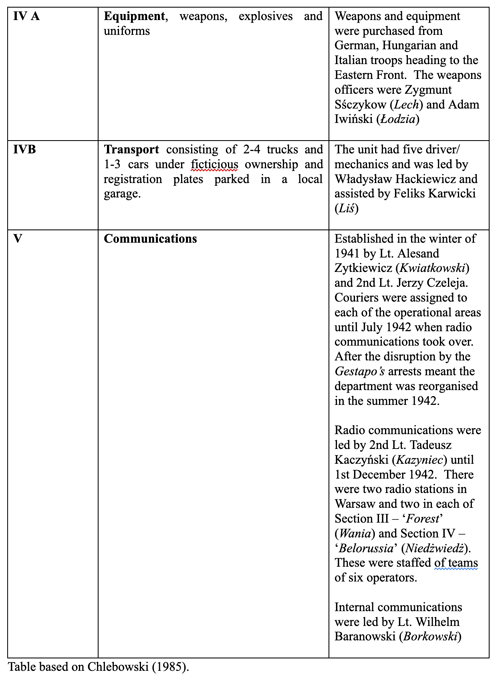

The plan used the word ‘contribute’ rather than other nouns like destruction since it shows a degree of military limitations imposed through the lack of resources and gives direction to the teams’ abilities. The commander of the Wachlarz, Lt. Col. Adam Grocholski (Brochwicz, Doktor, Iżynier) stipulated operational security, and counterintelligence would be managed through limiting access to the various units and the setting up of specific departments to control the operation into the following:

- Security led by Lt. Col. Grocholski

- Internal communications

- Organizational intelligence

- Operations

- Quartermaster handling both transport and communications.

The patrols would consist of an officer and four to six ORs with three to four patrols located in key areas and the sabotage was planned to coincide with each other (Chlebowski, 1985). There were two plans:

- Variant A: This was seen as the minimum plan to destroy 45 bridges including ones over the river Dvina and Dnieper including the access roads.

- Variant B: Blow up or burn an additional 100 bridges and roads leading to the east from occupied Poland.

On 1st December 1942, German counter-intelligence and the Gestapo almost destroyed Department V with the arrest of 2nd Lt. Tadeusz Kaczyński (Kazyniec) and 2nd Lt. Szczesniewski (Zuraw). The followiing day, more arrests threated to blow the network of couriers. As a result the couriers were controlled through the Chief of Staff to improve internal security.

The issue over the success or failure of the Wachlarz lay in the hands of the Government-in-Exile in London and the Allies shift in relations towards Stalin as an Ally, since the emergence of the eastern borders and the Curzon Line came into play during the development of the Sikorski-Maisky Agreement in July 1941. While thousands of Poles imprisoned by the Soviets were freed, the borderland covering eastern Poland would become a stumbling block in Polish and Soviet relations that became a ‘thorn in the side of Churchill and Roosevelt’. With the Wachlarz operating in a complex ethnic area made up of Poles, Ukrainians, Belarussians and Latvians together with a challenging landscape of swamps and forests, the overall conditions could not have been worse, but ideal for partisans. Once the area had now been declared to be in Soviet interests, the Poles felt betrayed. In effect the Treaty of Riga 1921 had been ripped up by Stalin.

Support Operations by Cichociemni

Polish Special Forces (Cichociemni) were dropped into Poland to bolster the quality of the units and provide instruction in sabotage, diversionary tactics, use of small arms and explosives and intelligence gathering. 27 Cichociemni were assigned to the operation which occurred in extremely difficult conditions since the operational areas had suffered from Soviet deportations and replaced by Soviet citizens and deportees from Lithuania and in some locations Volkesdeutch.

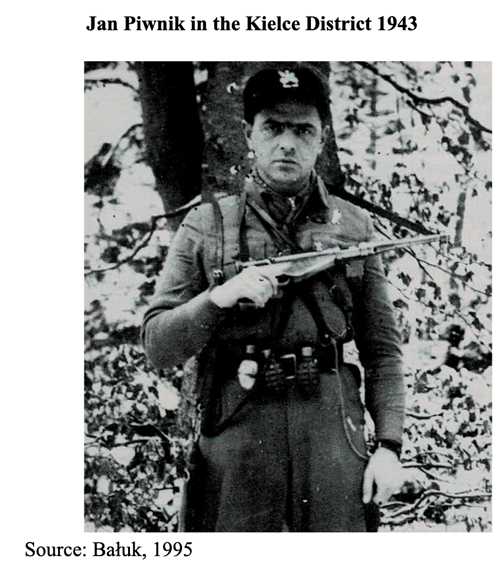

Jan Piwnik had been trained as a Cichociemni (Hyperlink: Cichociemni page) and dropped into Poland in Operation RUCTION on 1st-2nd November 1941 with Capt. Niemer Bidziński (Ziege) and a courier Lt. Napoleon Segieda who carried money to support ZWZ activities. They were dropped over Czatolin, 20Km from Skierniewic in the Łódź Voivodeship in central Poland with four W/T’s and radio receivers plus correspondence for the ZWZ.

Jan Piwnik was transferred to Równe in eastern Poland (Ukraine) until his arrest by the Gestapo in July 1942. Captured with him was Jan Rogowski, deputy commander who had been parachuted into Poland in Operation COLLAR on 3rd-4th March 1942. Piwnik managed to escape from prison and returned to Warsaw where he was ordered to lead the spectacular storming of the prison in Pińsk where he successfully released members the Wachlarz including Capt. Alfred Paczkowski (Wania) who was one of the first commanders of the Wachlarz and had trained as a Cichociemni in Britain. Paczkowski while operating in Section III had been arrested along with Marian Czarnecki (Rys, Ruski, Ignacy), the Deputy Commander of Section III; Piotr Downar (Azorek) and Mieczysł Eckardt (Bocian) who died during his interrogation by the SS (Cheblowski, 1985). All had been captured when trying to blow a bridge over the river Horyn to the east of Równe and an important communications transport link to the Eastern Front.

The raid was planned in a flat in Brześć by Piwnik after a guard tipped off the Wachlarz (Chlebowski, 1985) that the prisoners were being transferred to Pińsk. The impact of Gestapo raids almost caused the collapse of Section IV in Minsk that resulted in the Wachlarz to come under the command of the Kedwy (ibid). The city and prison were heavily fortified with a garrison of 3,000 Wehrmacht and Ukrainian troops. Although a bribe of 60,000 Reich Marks had been offered with no result, Piwnik decided an attack was the only option (ibid). Piwnik concluded the success would be based on surprise and the use of other Cichociemni to join the teams.

These consisted of:

- Group I: Led by Jan Piwnik (Ponury), Władysław Hackiewicz, (MSZ, Zaleski), Zbigniew Wojnowski, (Motor, Zbigniew Sulima) who was dressed as an SS officer.

- Group II: Lt. Jan Rogowski, (Czarka) Cichociemni from the COLLAR mission, Lt. Waclaw Kopisto, (Kra) Cichociemni from the SMALLPOX mission, Zbigniew Słonczyński, (Jastrzebiec, Jastrząb, Turoń, Dzik).

- Group III: 2nd Lt. Michał Fijalka, (Kawa) Cichociemni from the SMALLPOX mission, Wiktor Hołub, (Kmicic), Czesław Hołub, (Ryks), Skwierczyński, (LDym).

- Group IV: (Wrona), (Kruk), Władysław Westwalewicz, (Plomien).

- Group V: Edward Pobudkiewicz, (Montera), Henryk Fedorowicz, (Pakunek

- Group V: Edward Pobudkiewicz, (Montera), Henryk Fedorowicz, (Pakunek

Just before 17.00 on 18th January 1943 an Opel Kadet drove up to the gates of the prison. An SS officer (Zbigniew Wojnowski) rudely demanded the prison gates to be opened. As the car drove into the courtyard, a prison guard started to close the gates and was shot by Wojnowski. The second group entered the prison and ran across the courtyard into the prison offices and ripped out the phone cables and at the same time guarded the entrance hall. The next group entered the offices of the Oberwachtmeister and shot the occupants, one of whom managed to shoot Czesław Holub in the arm. On finding the prison keys, a team consisting of Czesław Holub, Zbigniew Słonczyński, Wiktor Holub and 2nd Lt. Michał Fijalka scaled an internal wall into the courtyard where the SS Officer Zbigniew Wojnowski distracted the guards who were overpowered. The Opel rolled into the inner courtyard to where the prisoners were held. Storming into the cells shouting in Russian to confuse any remaining prison guards, Paczkowski was released and bundled into the car and fled before being discovered.

The overloaded Opel burst its tyres before being rescued by a Ford truck driven by Edward Pobudkiewicz, (Montera) and headed towards Janów Poleski (in today’s Belarus) where they switched trucks to a Chevrolet that had a hiding place and made their way to Drohiczyn. The Ford truck acted as a decoy and headed towards Brest. Spikes were scattered across the roads to deter any pursuit.

It was all over in 15 to 20 minutes according to various accounts. Having sprung valuable AK officers from a heavily guarded prison in a daring raid, the ruse of being Soviet soldiers didn’t really work and the remaining 40 prisoners and the tragic end to 30 hostages highlighted the moral dilemas senior officers faced when planning covert operations (Chlebowski, 1985). Many of the teams headed towards Warsaw which took several days to avoid raising any suspicions.

Piwnik’s next assignment was to organise AK groups in the Radom area before his transfer to the Nowogródek District as leader of the VII battalion of the 77th Home Army Infantry Division. He was killed in action against the Germans during operation TEMPEST on 16th June 1944 near the village of Jewlaszcze (Śledziński, 2012, Turner, 2022). (Hyperlink: Warsaw Rising) His wife, Emilia Malessa (Marcysia) commanded the AK cell Zagroda consisting of about 100 couriers working on foreign communications at the AK HQ in Warsaw. She participated in the Rising and managed to escape from transports taking her to a labour camp. On the disbandment of the AK Marcysis was arrested for membership of NIE by the UB and tortured possibly giving away the identity of comrades on the premise no further action would take place by Józef Różański of the NKVD. Although pardoned by Bierut and shunned by former AK combatants, she committed suicide in 1949.

The following Cichociemni missions were sent to support the Wachlarz:

Operation BOOT 27th -28th March 1942 from Tempsford after an aborted flight in February. The team consisted of: Lt. Zbigniew Bąkiewicz (Zabawka), 2nd Lt. Lech Łada (Żagiew), Lt. Jan Rostek (Dan), Lt. Tadeusz Śmigielski (Ślad) and Rafał Niedzielski (Moncy). Accompanying them was a courier: 2nd Lt. Leszek Janicki (Maciej, Zasobniki) carrying money for the underground army and assigned to the Government Delegation. They were dropped over Przyrów, 34 Km from Częstochowa with their kit spread around the LZ taking time to retrieve it.

Lech Łada was assigned to Section II of Wachlarz at Równe and in the autumn 1942 formed a sabotage unit with the help of Gryzoni partisans (escaped Georgians) who joined the AK. Jan Rostek was transferred to the intelligence unit in Kiev and arrested on 14th January 1943 by the Abwehr and murdered. Rafał Niedzielski served with the Wachlarz diversionary unit in the Lvov – Tarnopol – Płoskirów – Winnica – Żmerynka area until joining the Ponury and carried on with sabotage. He was killed while attacking a train near Wólka Plebańska in August 1943.

Operation BELT took off 30th – 31st March 1942 at 19.05 from Tempsford in Halifax (L9613 V) for south-central Poland near Końskie. The team consisted of Maj. Jerzy Sokołowski (Mira), Capt. Tadeusz Sokołowski (Trop), Lt. Stefan Majewicz (Hruby), Lt. Piotr Motylewicz (Krzemień), and Jan Jokiel (Ligota). The courier Lt. Jerzy Mara-Meyer (Filip Zasobniki) also carried money to fund the local AK detachment. They were dropped 6Km from the planned LZ.

Sokołowski left for Warsaw before being transferred to the Wachlarz sabotage unit that operated behind the German Eastern Front and he was joined by Tadeusz Sokołowski and Piotr Motylewicz. On attacking a prison in Mińsk, many prisoners and the attackers were killed. Sokołowski survived and became an instructor at the diversionary school Zagajnik in Warsaw. In an assassination attempt on a German agent in Warsaw, he was shot and handed over to the Gestapo and taken to their HQ in Alei Szucha and tortured. Sentenced to death, he was transferred to Auschwitz on 5th October 1943 along with 1,500 prisoners.

The courier, Lt. Jerzy Mara-Meyer had been made head of the special branch to resist expulsions in the Zamość region where the Germans planned to develop a colony (Williamson, 2012). He was killed in the Battle for Wojda blocking the expulsion of Poles whose successful actions forced the Germans to abandon the plan.

Operation CRAVAT 8-9th April 1942 was the last one for the trial period. The Halifax (L9618 W) took off from Tempsford 8th – 9th April 1942 as the dark season was coming to an end for these missions. On board were Lt. Teodor Cetys (Wiking) who later wrote about his exploits, Lt. Stefan Mich (Jeż), Lt. Alfred Zawadzki (Kos), Lt. (General Staff) Henryk Kożuchowski (Hora), Lt. Roman Romaszkan (Tatar) and Lt. (General Staff) Adam Boryczka (Brona, Adam, Albin) and carried packages of money for the AK. They were dropped over Drzewicz, near Lake Dybrzk in the Pomeranian voivodship in northern Poland.

Adam Boryczka was engaged in sabotage operations against railway traffic and trained saboteurs at the Wachlarz commanding the AK Vilnius district between January and March 1943. The Gestapo ambushed him on 7th July 1943 and was wounded, requiring convalescence until August 1943. He Commanded an AK unit in the Rudnicka Forest (Brony) and was involved with many skirmishes until injured again on 1st April 1944 at Ostrowiec. On 7th July 1944 he attacked a column of escorted prisoners with many hundreds escaping into the surrounding countryside. When the NKVD entered Vilnius, AK soldiers were forced to lay down arms or join the Soviet Army. He fled to the Rudnicka Forest and met up with other units commanded by Lt. Col. Janusz Prawdzic-Szlaski and Lieutenant Colonel Maciej Kalenkiewicz. He remained in the forests until the disbandment of the AK.

Henryk Kożuchowski was assigned to the 3rd Operational Department in Łódź District and was subsequently arrested by the Gestapo on 5th December 1942. In June 1943 he escaped, and the AK’s counterintelligence had evidence the escape was staged and sentenced to death for treason which was carried out. He was rehabilitated by a commission in 1980. Zawadzki was assigned to the 3rd Operational Department in the Silesian district. In December 1942, he was arrested by the Gestapo on the Piotrowice railway station and transferred to Cieszyn and murdered.

In the autumn of 1942, the Home Army reorganised and organisations such as Wachlarz, ZWZ and Osa (Special Combat Actions) who operated in the General Government area who specialised in assassinations, became part of a more cohesive and unified organisation called Kedyw (Kierownictwo Dywersji) or Directorate of Sabotage and commanded by Brig. General Emil August Fieldorf (Nil, Maj) from December 1942 to March 1944 and later replaced by Lt. Col. Jan Mazurkiewicz (Radosław) until August 1944 (Garliński, 1975; Bałuk, 1995, Williamson, 2012).

Operation SMALLPOX took off from Tempsford in Halifax (W7773 S) also on 1st – 2nd September 1942. The team consisted of Capt. Bolesław Kontrym (Żmudzin), Lt. Mieczysław Eckhardt (Bocian), Lt. Hieronim Łagoda (Lak), Lt. Leonard Zub-Zdanowicz (Ząb), 2nd Lt. Michał Fijałka (Kawa) and Lt. Wacław Kopisto (Kra). They were dropped over Łoś-Bogatki area between Grójec and Warsaw.

Kontrym was assigned to the Wachlarz for sabotage operations at the beginning of September 1942. He took part in the storming of the prison at Pinsk and later became head of security of the Central Investigation Service liquidating agents and informers. During the Warsaw Uprising in 1944, he commanded 4th Company and wounded four times. Appointed commander of the 3rd battalion (36th Infantry Regiment) until capitulation and sent to POW camps: Lamsdorf, Fallingbostel, Bergen-Belsen, Gross-Born and Sandbostel from where he escaped in April 1945. From May 1945, he was deputy commander of the 9th Flanders Rifle Battalion attached to the 1st Polish Armoured Division. Mieczysław Eckhardt was assigned to the Łoś-Rogatki forest district, north-east of Grójec. He was arrested on 19th November 1943 and was murdered.

The Kedwy was an element within the planned Operation BURZA (Storm or Tempest) to capture occupied cities from the Germans and disrupt their ability to hold their positions on the Eastern Front. The operation started in central Poland and covered the General Government, Dąbrowa Basin, Kraków Voivodeship, Białystok and Brześć areas where the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) were a threat to areas associated with the Curzon Line. The operations covered sabotage, diversionary activities, destruction of rail networks and reprisals with self-defence from German, Soviet and the UPA attacks (Bałuk, 1995).

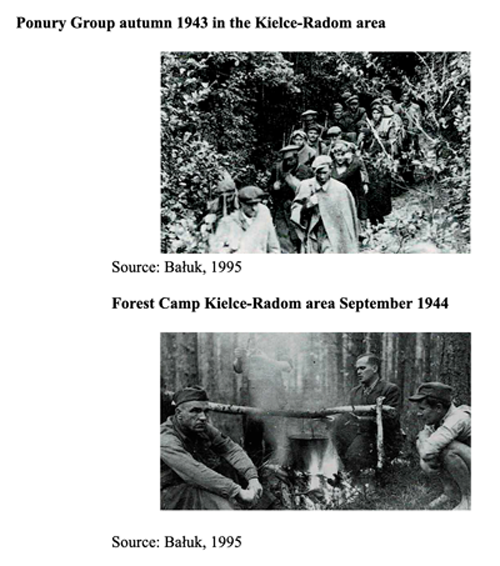

Action Końskie took place in August 1943 and was a local independent operation from the main Wachlarz. In the Końskie forests to the south-east of Łódź, were the AK’s ‘Ponury’ unit commanded by 2nd Lt. Waldemar Szwiec (Robot) who was parachuted into Poland in Operation CHISEL on 1-2nd October 1942 (Śledziński, 2012). The surrounding area around the city was partially controlled by the AK and presented a threat to the security of the rear lines of the Wehrmacht who regarded the surrounding district as ‘bandit country’. The German position on the Eastern Front was precarious after the German Group B army almost annihilated in Stalingrad and further north, the Battle of Kursk (Soviets called it Operation KUTUZOV) salient became one of the largest single battles of the war in July 1943. With the invasion of Sicily, Hitler needed a strategic victory to prove to the wavering support from the Axis that the war could swing into their favour.

On 20th August the city was surrounded by Wehrmacht units and the Gestapo entered the city to arrest the district commander Jan Rusinow along with 2nd Lt. Józef Sapetto and 2nd Lt. Stanisław Strzemieczny who were on the “wanted lists”. Many of the captured were sent to Auschwitz and the leaders interrogated at Gestapo headquarters in Radom. A number of Ponury units were in action elsewhere on the 19th-20th August and not caught up in the roundup. 2nd Lt. Szwiec had 64 men at his disposal and sought to avenge the arrests through a spectacular operation that coincided with the anniversary of Germany’s invasion of Poland on the 1st September 1939.

At 22.00 three groups of Ponury began to position themselves for a surprise attack on the city. One group held the old toll gates on the eastern side while another group crossed over countryside to the north of the city to block the Wehrmacht barracks. 2nd Lt. Szwiec attacked the local transformer electricity station to the city. The signal for action was the cutting off the power supply at midnight. German counterattacks were ineffective and 2nd Lt. Szwiec’s team raided the food stores owned by Społem and loaded onto a truck. During the attack, a three-man team led by Stanisław Janiszewski (Dewajtis) liquidated five informers who had been sentenced to death by a special underground court for treason. After two hours of fighting with no casualties, the AK slipped away south towards Czerwony Most on the outskirts of the city and safety.

The Wachlarz operation culminated in the Warsaw Uprising and Operation BURZA (Link: The Warsaw Rising)

The AK carried out 1,175 operations mainly against rail communications with 38 bridges destroyed, 19,058 railway carriages, 1,165 fuel tankers, 272 munitions dumps, and more than 2,000 Gestapo informers were executed (Bałuk, 1995). The casualty rates amongst the Cichociemni were about 40% with survivors being sent to train other cells in different regions for Operation BURZA or participate in the Warsaw Uprising. In a report filed by SOE’s E/UP Section confirmed that by the end of the war, the AK had destroyed 1,268 locomotives, 3,318 railway trucks and carriages, burnt 76 railway transports heading to or from the Eastern Front, 25 derailments, 90 interruptions and delays to rail transports, 7 bridges destroyed, 148 railway points cut, and 2 railway workshops destroyed by fire (Maresch, 2005). The list of industrial damage to factories is equally impressive and curtailed further criticism by the Soviets (TNA/ HS7-184).

Postscript:

During the Warsaw Uprising, Fieldorf was Deputy Commander of the AK. Later, on 7th March 1945 he was arrested under a false name by the NKVD and taken to a gulag in the Ural Mountains and released in 1947. On returning to Poland, he remained ‘underground’ and was in contact with NIE. He was duped into giving himself up to the authorities and was rearrested. A communist inspired ‘show trial’ prosecuted him as a ‘Fascist-Hitlerite’ and sentenced to death on 16th April 1952. Pardons and petitions by the family were ignored by the then President Bolesław Bierut. Emil was hanged at Mokotów Prison on 24th February 1953 – one of the many shameful incidents by the Communist installed government.

Lt. Napoleon Segieda (Wera) went to Osiek 12Km from Oświęcim and stayed with Wladyslaw Jekiełek reporting on the activities within Auschwitz who went on to pass on his report to the Allies (Tochman, 2021).

Capt. Alfred Paczkowski (Wania) after a short ‘sojurn’ in Warsaw returmed to command the Białystok Area Kedyw then he commanded the 84th Infantry Regiment in the 30th AK Infantry Division. Seriously injured at the Battle of Mańczaki (Monchaki, Belorusse) in Operation BURZA on 6th June 1944, he was sufficiently recovered to participate in contacting the Soviets across the Vistula river during the final days of the Warsaw Uprising. He was arrested by the NKVD and sent to a camp number 150 in Griazowiec near Vologda in Russia in July 1947. Released under an amnesty, he spied on the Polish communist security services for the underground and lost his job as a doctor.

Czesław Hołub survived the war and was arrested on 18th December 1946 in Olstyn and sentenced to death. He was released under an amnesty in 1956 and remained under surveillance by the UB and despite this, he organised strikes in December 1970, August 1980 and December 1981.

2nd Lt. Szwiec was betrayed and killed on 14th October 1943 during anti-partisan raid on the Wólka Zychowa forest to the east of Końskie where his unit was based. A few escaped and fought their way to the Wykus forest between Kielce and Radom.

Operation WACHLARZ was regarded by Britain’s Foreign Office as ‘experimental’ and achieved limited results (Williamson, 2012). However, based on the evidence of the missions and the level of sabotage and destruction (Maresch, 2005), the Foreign Office assessment falls short of the actual achievement given the logistics and demands on supplying resistance movements in Europe, the Balkans and Scandinavia at that time. The level of dismissive criticism by the Foreign Office over Polish achievements masked the reality of the AK’s success, particularly in the collection of intelligence and the scale of disruption behind the Eastern Front. It was not until the supply of ground to air transmitters (S-Phone, Rebecca and Eureka Beacon Systems) improved supply drops to the AK that saw a significant impact on the German occupation in breaking vital rail communications and destruction of industrial output through sabotage (Hyperlink: Home Army & SOE/ Operation Jula and Ewa) and their ability to wage an effective guerilla war (Maresch, 2005). The calendar of operations and the list of AK combatants in Chlebowski’s (1985) seminal work further strengthens the fact that the Foreign Offices’ myopic stance on the successes of the Polish guerrilla war was misguided.

Selected References

Bałuk, S.S. (1995) “Poles on the Frontlines of World War II, 1939-1945”, ARS, Poland, Chapter X.

Chlebowski, C. (1985) “Wachlarz: Monografia Wydzielonej Organizacji Dywersyjnej Armii Krajowej wrzesień 1941 – marzec 1943”, Instytut Wydawniczy Pax, Poland.

Garliński, J. (1969) “Poland, SOE and the Allies”, George Allen and Unwin Ltd. U.K.

Garliński, J. (1975) “The Polish Underground State (1939-45)”, Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 10, No.2, pp.219-259.

Klimecki, M (ND) “Combat involvement of Poland’s 27th Infantry Division of the Volhynia Home Army against the UPA in light of the 27th’s entire combat trail, https://zbrodniawolynska.pl/ftp/zbrodnia_wolynska/Combat-involvement-of-Polands-27th-Infantry-Division-of-the-Volhynia-Home-Army-against-the-UPA-in-the-light-of-the-27ths-entire-combat-trail.pdf (Accessed 14.11.2024)

Maresch, E. (2005) “SOE and Polish Aspirations”, in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch18

Śledziński, K. (2012) Cichociemni (Elita Polskiej Dywersji)”, Społeczny Instytut Wydawniczy, Poland.

Tochman, K, A. (2021) “Zapomniany kurier do Delegatury Rządu. Ppor. Napoleon Segieda “Wera” 1908-1991”, Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, Vol.20, No.3, pp.55-77.

Turner, D. (2022) “The Secrets of Station 14”, The History Press, UK.

Williams, D.G. (2012) “The Polish Underground 1939 – 1947”, Pen & Sword Military, U.K.

Additional Useful References:

Banasikowski-Weir, J. (2021) “The Memory of Sacrifice and the Sacrifice of Remembering”, Church Life Journal, November 02, (Accessed 29.10.2024).

Biniecki, W and Murawska, K. (2024) “Colonel Edmund Banasikowski – a Steadfast Soldier in Exile”, Kuryer Polski, 31st October 2024 (Accessed: 31.10.2024)

Chlebowski, C. (1988) “Pozdrówcie Góry Świętokrzyskie”, Epoka, Poland

Fairweather, J. (2019) The Volunteer: One man, an underground army, and a secret mission to destroy Auschwitz”, Custom House, USA.

Jasiński, G (Ed.) (2015) “Kronika Wojska Polskiego 1944” Wojskowe Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej, Poland.

Krzyżanowski, J.R. (2004) “Warsaw Uprising 1944: Part One”, Dialogue and Universalism, Vo. 14, No. 5/6, pp.37-50.

Motyka, G. (2022) From the Volhynian Massacre to Operation Vistula: The Polish - Ukrainian Conflict 1943-1947”, Centre for Historical Research of the Polish Academy of Sciences Berlin, Germany.

Ney-Krwawicz, M. (2001) “The Polish Resistance Home Army 1939-1945”, PUMST, UK.

Paczkowski, A. (1984) "Ankieta Cichociemnego”, Institut Wydawniczy, Poland.

Paul, M. (2017) Neighbours on the eve of the Holocaust: Polish-Jewish relations in Soviet-occupied Poland, 1939-1941”, Pefina Press, Canada.

Szatsznajder, J. (1985) “Cichociemni Z Polski Do Polski”, KAW, Poland.

Zimmerman, J.D. (2015) “When the Polish Underground Helped the Jews: Individual Aid” in “The Polish Underground and the Jews under Nazi Rule, 1941-1945”, Cambridge University Press, UK, CH. 12, pp.319-349.

Selected Films:None Known

|