Operation WIENIEC (GARLAND)

7th – 8th October 1942

Introduction:

Operation WIENIEC was part of a wider sabotage operation that had been instigated by the Polish resistance to meet its and SOE’s aspirations for disruption throughout the Reich in the spring of 1942 (Bałuk, 1995; Maresch, 2005). The operation was undertaken by Związek Odwetu (Union of Retaliation) on the 7th – 8th October 1942 as a precursor to future operations by the ‘Home Army’ (Armia Krajowa).

The Związek Odwetu had been formed by Maj. Gen. Stefan Rowecki in April 1940 as the sabotage and diversion wing of Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Union of Armed Struggle), a forerunner of the AK. The operation was initially led by Maj. Franciszek Niepokólczycki (Teodor, Franek), a Russian born Pole and career officer who had fought in the Polish-Soviet War in 1920 and in the defence of Poland in 1939 with an engineer battalion (60th Sapper Battalion) with Army Modlin. Later, he would become head of the Directorate of Sabotage and Diversion (Kedyw) of the AK.

The sabotage proposals which covered Operation WACHLARZ (called the ‘Big Scheme’ by SOE) had been submitted on 25th March 1942 and despite limited supply of explosives dropped over the winter of 1941/42, the plan looked viable for the planned disruption. Sikorski gave the operation the ‘go-ahead’ in August 1942 after consultation with SOE and would establish the extension of the armed struggle against the German occupation. The abhorrence to the Poles was in the sharing of Polish intelligence via the Foreign Office with the Soviets (Maresch, 2005). Gubbins had written to Frank Roberts in the Foreign Office that British support for the AK was in response to their support of the Allies and the quantity in quality intelligence gathered in Poland that also benefitted the Soviets (ibid).

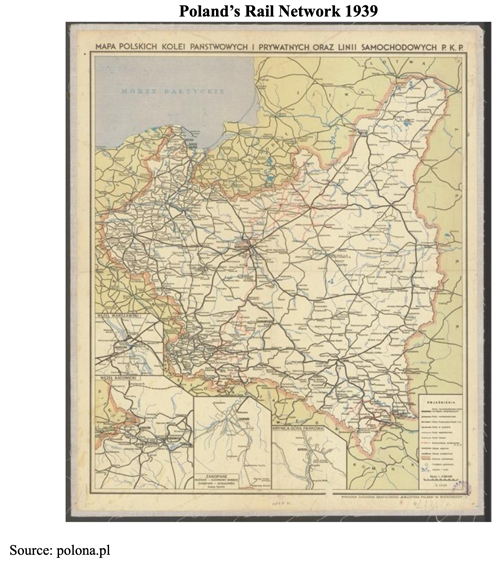

During the 1920s Poland invested heavily in its rail network to meet the demands of its growing industrialization and ability to export or import from neighbouring countries like Romania. The network not only reflected its location of resources, but also strategic capabilities safeguarding its boundaries from the Soviets in the east and Germany’s post war foreign policy towards its new neighbour, Poland who was seen by them as a threat to the balance of power in Europe.

The Operation:

Against the backdrop of sabotage and diversionary operations were the threats by the Germans of retaliatory killing of civilians and prisoners held in the Pawiak prison in Warsaw. The plan was to disrupt railway traffic in and around Warsaw, an important hub for rail communications to the Eastern Front.

The plan would use the distraction of a Soviet bombing raid on Warsaw to cover the explosions and disguise the saboteurs to remove or lessen the threat of reprisals. Col. Antoni Chruściel (Monter) who commanded the Warsaw District of the AK pulled together teams of sappers. Led by Capt. Jerzy Lewiński (Chuchro). Key railway junctions were to be sabotaged to delay rail engineering units and key war materials destined for the Eastern Front which would assist the Soviets during a critical period on the front in 1942.

Seven teams included two made up of women, were given specific tasks for the night operation. Lt. Zbigniew Lewandowski (Zbyszek, Szyna), Lt. Józef Pszenny (Chwacki) who commanded the Praga Sappers and Lt. Józef Pszenny had reconnoitred suitable targets for maximum effect. The plans were approved by Col. Antoni Chruściel and Maj. Franciszek Niepokólczycki, however, the Soviet bombing raids failed to materialise in the summer and autumn of 1942. The operation went ahead due to the delay was having unnecessary consequences for local morale and its needed strategic impact on the Eastern Front.

Seven teams included two made up of women, were given specific tasks for the night operation. Lt. Zbigniew Lewandowski (Zbyszek, Szyna), Lt. Józef Pszenny (Chwacki) who commanded the Praga Sappers and Lt. Józef Pszenny had reconnoitred suitable targets for maximum effect. The plans were approved by Col. Antoni Chruściel and Maj. Franciszek Niepokólczycki, however, the Soviet bombing raids failed to materialise in the summer and autumn of 1942. The operation went ahead due to the delay was having unnecessary consequences for local morale and its needed strategic impact on the Eastern Front.

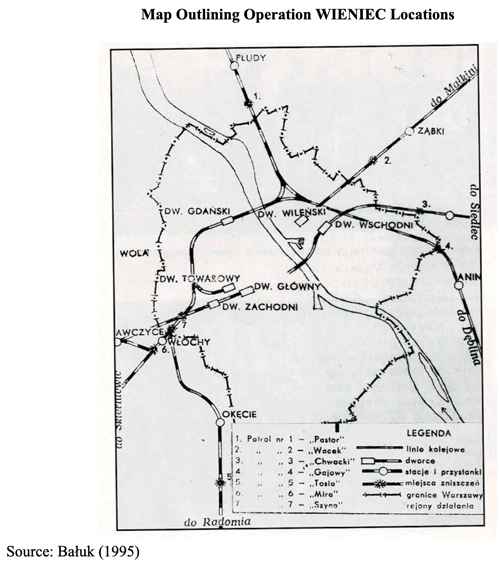

The final plan was to blow railway lines in four places on the right bank of the river Vistula and three on the left bank.

Lt. Zbigniew Lewandowski (Zbyszek), Lt. Józef Pszenny (Chwacki) and Lt. Leon Tarajkowicz (Leon) had to reconnoitre and re-evaluate the locations in September 1942 before the final preparations could be completed. Lewandowski and Pszenny commanded the operation with AK patrols attacking two other locations during the night as diversionary actions. The locations of the actions on the right bank were:

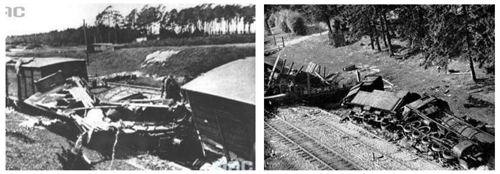

- Warsaw to Małkinia near Zielonka was attacked at 0.25 by a unit led by Sgt. Wacława Kłosiewicz (Wacka) who derailed a train and destroyed two railway tracks blocking train transports towards Białystok. The team consisted of: Jan Górski (Grot) and Zygmunt Orłowski (Orzeł)

- Warsaw to Dęblin near Anin on the outskirts of Warsaw, was attacked at 0.27 by a unit led by 2nd Lt. Mieczysław Zborowicz (Gajowy) derailing a train and blown two railway lines across a bridge. The explosion shook the town of Anin and blocked southern-bound railway traffic for ten hours.

- Warsaw-Siedlce near the suburb of Rembertów was attacked at 02.00 by Lt. Józef Pszenny who allowed part of a medical train to pass through before blowing the line and damaging the rear carriages. The railway line was blocked for seven hours. The team consisted of: Józef Łapiński (Chmura), Jerzy Obidziński (Obój) and Henryk Witkowski (Boruta).

- Warsaw- Działdowo line near Płudy by 2nd Lt. Lieutenant Władysław Babczyński's (Pastor) unit. The team consisted of: Marian Dukalski (Marek), Zygmunt Puchalski (Atomek), Piotr Puchalski (Łotr) and Zygmunt Puterman (Kowal).

The train was derailed, but the carriages remained intact due to the train travelling slowly. The line was closed for seven hours.

- Mining patrols around Warsaw were led by Zofia Franio (Doktor) carrying out diversionary and liquidation actions.

The locations of the actions on the left bank were:

- Two tracks on Włochy-Warszawa-Zachodnia suburban line, two tracks cut between Włochy and Warszawa Towarowa and one track on Warszawa Zachodnia-Radom line by Lt. Zbigniew Lewandowski’s unit. Railway traffic was interrupted between five to seven and a half hours.

- On the Radom line between Okęcie-Piaseczno section near the suburban Pyry railway station in southern Warsaw, the unit led by Antonina Mijal (Tosia) and Irena Hahn (Isia) derailed a train.

- On the Radom line between Okęcie-Piaseczno section near the suburban Pyry railway station in southern Warsaw, the unit led by Antonina Mijal (Tosia) and Irena Hahn (Isia) derailed a train.

- On the branch-line between Skierniewice and Błonie to the west of Warsaw, the tracks were blown by Lt. Stanisław Gąsiorowski's Unit Mieczysław.

Despite the Poles indicating the operation was done by Soviet paratroopers, arrests among the railway workers led the Gestapo to none of the conspirators. The retribution commenced. Gallows were constructed on the 15th to 16th October 1942 around Warsaw. The Gestapo were frustrated by the ‘wall of silence’. Under the pretext of the retaliation, it is thought the 50 victims were workers from the Polish Workers Party and the People’s Guard who had been rounded up in September 1942. A further 39 people from the Pawiak prison were executed in the Kampinos Forest on 15th October as a method to discredit the AK and put terror into the minds of the Varsovian population.

Postscript:

Operation WIENIEC was a great success. It proved to the leaders of the AK and Gubbins, head of the SOE that well planned and executed operations in Poland could inflict significant damage to Germany’s war-machine, its morale and tied-up much needed front-line troops on anti-partisan operations (Maresch, 2005). A month later, the embattled Germans’ suffered defeat at Stalingrad in a bold Soviet counter-offensive and it is recognised as the turning point on the Eastern Front. In north Africa, the Second Battle of El Alamein ended the Axis threat to the Middle East and prompted its retreat to Tunisia.

Col. Antoni Chruściel, a career officer became the commander of the Warsaw Uprising in 1944 and taken prisoner where he ended up in the infamous Colditz castle. He planned his return to the now Soviet controlled Poland and like many senior officers, was denied citizenship and faced a lengthy prison sentence. On demobilisation, he lived for a short period in London before moving to Washington, D.C and practised law.

Col. Franciszek Niepokólczycki, architect of Operation WIENIEC, was chief of the engineers (sappers) 3rd Regiment during the Warsaw Uprising of 1944. After the surrender, he was transferred to the POW camp at II C Oflag at Dobiegniew (Woldenberg) and released in early 1945 by the Soviets. He was a member of WiN (Freedom and Independence) movement and was captured in Kraków on 22nd October 1946. He was sentenced to death that was commuted to life imprisonment. On 22nd December 1956, he was released with numerous political prisoners under a general amnesty to former combatants by the communist regime.

Lt. Zbigniew Lewandowski was assigned to the AK HQ Dept. III in Warsaw as part of the Kedyw specialising in sabotage. He participated in the Warsaw Uprising of 1944 and was captured and sent to POW camp at II C Oflag at Dobiegniew (Woldenberg) that was also a hard labour camp until liberation.

Lt. Józef Pszenny (Chwacki) became commander of the Sapper Department of XII District in Warsaw. He was responsible for blowing up part of the walls surrounding the Jewish Warsaw Ghetto on 19th April 1943 during the uprising to provide an escape route. He continued in his role of saboteur and on 11th to 12th September 1943 attempted to steal an armament train bound for the Eastern Front at Halinów on the Warsaw- Siedlce line and later between 31st August and 1st September 1943 blew railway lines around Warsaw in Action Końskie. Again, on 11th and 12th September 1943 he was responsible for attacking the railway lines at Halinów on the Warsaw- Siedlce line. Not being deterred, he again led a unit to attack the railway lines at Dębe Wielkie station 31Km from Warsaw on 4th to 5th October 1943. The disruption in resupply to the already stretched German troops to the east enabled the Polish 1st Tadeusz Kościuszko Infantry Division who were engaged in the Battle of Lenino, Byelorussia to make further advances west.

Zofia Franio (Doktor) participated in the Warsaw Rising and was assigned to a sappers’ unit who captured a key building in the city centre. She escaped the German roundup hidden in a group of fleeing civilians. As a member of WiN, she was arrested by the security services on 14th November 1946 and sentenced to 12 years in prison and was released on 15th May 1956. She had a distinguished career after the war.

Lt. Leon Tarajkowicz (Leon) was killed during the Warsaw Rising by Einsatzkommandos. Jan Górski (Grot) and Józef Łapiński (Chmura) who with Władysław Babczyński's (Pastor) had attempted to free Jews from the ghetto uprising in 1943 by blowing the wall on Bonifraterska Street, died in combat during the ‘Rising. Władysław Babczyński was shot by the Germans in 1944 after the rising failed. Piotr Puchalski (Łotr) also died during the ‘Rising.

Selected References

Bałuk, S.S. (1995) “Poles on the Frontlines of World War II, 1939-1945”, ARS, Poland, Chapter X.

Maresch, E. (2005) “SOE and Polish Aspirations”, in Sterling, T; Nałecz, D and Dubicki, T (Eds) “The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee Vol.1”, Valentine Mitchel, UK, Ch18.

Selected Websites:

https://www.polskieradio.pl/39/156/artykul/3048870,akcja-wieniec-czyli-walka-armii-krajowej-z-niemieckimi-pociagami

https://military-history.fandom.com/wiki/Armia_Krajowa

http://cichociemni.edu.pl/en/home/

https://polona.pl/item-view/6633bbfd-5560-4439-8f48-e3e84ee8d954?page=0

https://historia.dorzeczy.pl/druga-wojna-swiatowa/358363/akcja-wieniec-jak-polacy-zatrzymali-niemiecki-transport-na-wschod.html

https://muzeum-ak.pl/kalendarium-ak-wpis/akcja-dywersyjna-na-szlakach-komunikacyjnych-pod-kryptonimem-wie/51/

http://cichociemni.edu.pl/en/home/

https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/english/274796,dr-zofia-franio

hhttps://warhist.pl/polska/akcja-wieniec/

https://muzeum-ak.pl/kalendarium-ak-wpis/akcja-dywersyjna-na-szlakach-komunikacyjnych-pod-kryptonimem-wie/51/

Selected Films and YouTube Clips:None Known

|