Warsaw Ghetto Uprising 1943

Introduction

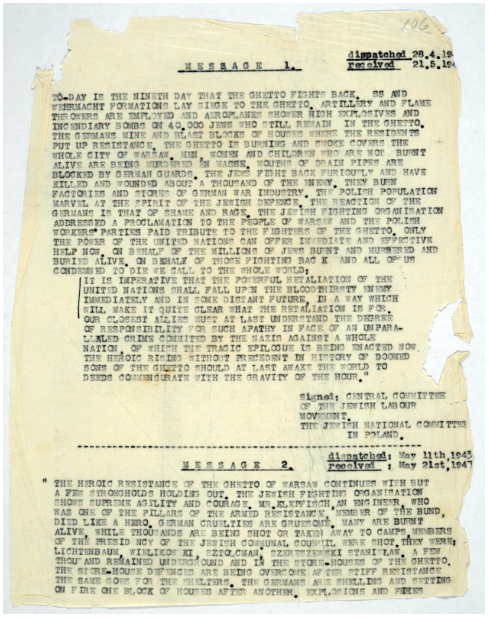

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943 was the largest amongst the Jews and was not planned to the same level of detail as the AK’s ‘rising that would take place in 1944 (Paczkowski, 2003). Despite Col. Antoni Chruściel, local commander of the AK ordering transfer of arms into the ghetto (Zimmerman, 2017) prior to the uprising. Success was not counted on but acted as a statement of dignity and an act of ‘amidah’ (to stand up against) against the Nazi oppression in the face of wider indifference to their fate (Gutman, 1994; Paczkowski, 2003; Kassow, 2007; Kochanski, 2012; Zimmerman, 2017; Fairweather, 2019). Even today, the sheer scale and horror shocks younger generations of the Nazi’s genocide inflicted across occupied Europe. The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising remains a powerful example of resistance during the Holocaust.

Prelude to the War:

Delegates from 32 countries met in the French resort of Evian-les-Bains between 6th and 14th July 1938 to discuss options for the evacuation of Jewish refugees fleeing the Nazi Third Reich (Brustein and King, 2004; Brustein, 2011). The Treaty of Versailles in 1919 had left many countries with minorities in the wrong country and the German perception of brutal reparations was exploited by the Nazis who blamed the communists, liberals, and the Jews through its propaganda to fuel hatred (Anon, 2012). The delegates witnessed world-wide indifference and the great democracies turning their backs on the fate of the German and Austrian Jewish refugees upon which provided the Nazi propaganda machine a bonanza on the eve of the Holocaust (Brustein and King, 2004).

Since Hitler’s election in 1933 and becoming President of the Third Reich, the Nazis exploited any opportunity to inflame hatred through a mixture of patriotism and racism not witnessed on such a scale. The Nuremberg Laws excluded Jews from social, economic, and political life in Germany from 1933 to 1935 Jewish businesses were boycotted with entry into the civil service and professions banned. Antisemitism formed part of the Nazi education system to instil disinformation and build myths about the Jews (Keskin Yilmaz, Çaki and Kazaz, 2020)

On November 9-10th 1938 Kristallnacht unleashed a reign of terror against the Jews in Germany and Austria on an unprecedented scale. Businesses and synagogues were destroyed with over 30,000 Jews arrested and sent to concentration camps. The newly elected mayor of the Free City of Danzig (Gdańsk), a Nazi sympathiser did little to prevent the destruction of the city’s synagogues and businesses that was a clear forewarning to Poland’s Jewry.

Hungary and Czechoslovakia refused to give refuge to the expelled Sudetenland Jews, the USA failed to pass the Wagner-Rogers Child Refugee Bill which would have saved 20,000 children and Britain closed Palestine to Jewish immigration with Argentina, Brazil and the papal authorities reneging on pledges to accommodate refugees (Brustein and King, 2004)

An empirical study by Brustein and King (2004) indicated there were several concepts that help explain the rise of anti-Semitism in Europe between 1899 and 1939. These ranged from the role of modernization which provided emancipation for the Jews, relative deprivation, ethnic competition and of scapegoating or frustration-aggression models that supported the conditions within Europe. While concepts provide an analytical tool, Brustein and King concluded a relationship between declining GDP and rise in anti-Semitism was the catalyst for the Holocaust does not provide the answer to depravity, inhumane acts and genocide that faced Europe’s Jewry.

The failure of the conference at Evian-les-Bains acted as a catalyst for individuals and organizations to act on saving Europe’s Jewry, especially the displaced children from central Europe. Individuals such as Nicolas Winton (Wertheimer) responded with selfless devotion and tireless enthusiasm to rescue as many children as possible. Invited to Czechoslovakia as a member of the British Committee for Refugees by Martin Blake in December 1938, Winton visited refugee camps filled to capacity of displaced Sudetenland Jews and political opponents of Nazism. Under the guise of the committee, Winton opened offices in Prague to register children who could be rescue as many believed war was immanent after Hitler’s threats to occupy Bohemia and Moravia. On his return to London, Winton raised funds to cover the British government’s ‘guarantee’ and sought out suitable foster homes for the “Kindertransport” to begin with the first trainload arriving at Liverpool Street Station in August 1939. Other organizations such as the German backed Reich Association and Jewish Community Organization provided transport to Dutch and Belgian ports to Harwich which saw some 10,000 children rescued that also sealed the fate of their parents (Hammel, 2020).

German Invasion of Poland

With Poland annexed on 29th September, Germany set up in central Poland around the city of Kraków the General Gouvernment with Warsaw still being the centre of Polish and Jewish life. Eastern Poland under Soviet control implemented mass deportations to the east. What followed was an almost endless series of decrees by the Nazis against both Poles and the Jewish community whom the Nazi’s regarded as ‘sub-human’. The incremental and oppressive decrees saw the confiscation of Jewish owned properties and businesses and then imposed forced labour and mass deportations to labour camps and the wholesale deterioration in life (Gutman, 1994). On 23rd November 1939 all Jews were required to a white ribbon with the blue star of David on the sleeve of their outer clothing with the decree stating all shops had to show their Jewish ownership and on 11th December forbidden to change place of residence that was now under the supervision of the governor-general. A few days later, all property and possessions owned by Jews had to be registered with the authorities and could no longer use railway transport without special permission (Gutman, 1994).

The pogrom of isolation and segregation continued with barring of entering professions, restaurants and bars or even public places and special carriages were set aside on public trams. While a general curfew was imposed in September 1940 across German held Poland, for the Jews this came into force an hour earlier. The loss of common civility, humiliation, degradation, and stress seeped into every aspect of Jewish daily life as they were dismissed from jobs and lost pension rights or money in bank accounts and even access to social welfare.

The introduction of the Judenrat in major cities by Reinhard Heydrich on 21st September 1939, as head of the Reich Security Main Office (RHSA) placed full responsibility on selected Jewish elders to ensure Nazi orders and decrees were carried out. The random arrests and kidnapping for labour undermined the role of the Judenrat which forced them to compromise and begin filling quotas through forming groups of organisers and supervisors – the Ghetto Police (Gutman, 1994; Kassow, 2007). The role and function of the Judenrat remains controversial today as when it came into existence with the treatise by Hannah Arendt (1977) fuelling a lively and controversial debate that has not subsided over time (Bilsky, 2001; Lederman, 2013; Gablenz, 2020).

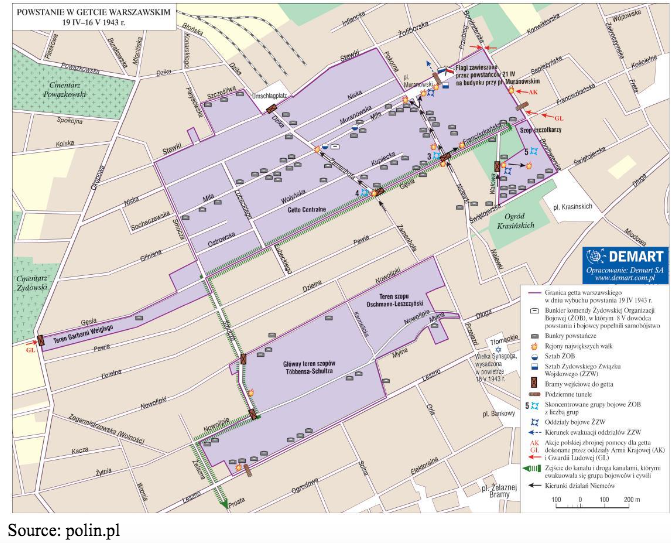

The ghettos in major cities had slowly taken shape in compact areas often close to railheads since July 1940. The Warsaw Ghetto (named as the Jewish Residential Quarter of Warsaw) was labelled ‘an infected area’ in March 1940 and the Judenrat ordered to build a wall to seal the inhabitants in which by October 1940 saw restrictions on any movement and neighbouring Poles forced to leave (Fairweather, 2020). Not all could find accommodation within the ghetto, so the Nazis extended the date to 15th November 1940 with many hoping this would enable work outside the ghetto to continue. On 16th November 1940, the ghetto was sealed.

The AK were aware of what lay ahead for the Jews. The courier, Aleksander Wielopolski had been released from Auschwitz at the end of October 1940 and made his way to Warsaw where he met Stefan Witowski, the Musketeer and Stefan Rowecki, deputy AK leader who was interested in seeking out clear evidence of the German crimes against prisoners under the 1907 Hague Convention (Fairweather, 2019).

Captain Witold Pilecki who as Tomasc Serafiński, was arrested and taken to Auschwitz 1 on the order of the AK who wanted to establish an underground movement in the labour camp and sabotage cells in the factories (Kochanski, 2012). His role also covered lessening the harsh conditions through securing medical and food supplies, attacking the most brutal kapos, spies and SS men (Fairweather, 2019). Within the factories making war-based materials, some production was secretly diverted into making guns and grenades (Kochanski, 2012). The inmates terrorised the worst camp guards by infecting them with Typhus-infected lice and the general recognition that these people were being targeted saw some limited improvements to conditions as few survived the infections (Kochanski, 2012). Pilecki named the underground movement ZOW (Związek Organizacji Wojskowej) whose role saw some 600 escapes that had a 30% success rate which including two Jews Rudolf Vbra and Alfred Wetzler whose report (Auschwitz Protocols) on the holocaust was broadcast by the BBC on 15th June 1943 (Kochanski, 2012). Pilecki escaped on 27th April 1943 and played a significant role in the Rising’ 44 (Davies, 2003).

Napoleon Segieda, a British trained agent, infiltrated Auschwitz in 1942 and reported on the industrial scale in the killings. Plans were made to ship him back to the UK to report to the Government in exile and the Allies (Fairweather, 2019). Napoleon was replaced by the courier Jan Karski whose diplomatic mission to the USA in November 1942 reported on the mass killings taking place (Nowak, 1982; Gutman, 1994; Kochanski, 2012; Zimmerman, 2017; Fairweather, 2019). Karski who was an experienced courier, had survived Gestapo torture when captured in Slovakia and ‘faked’ an attempted suicide and thereby managed to escape from his detention in an SS designated hospital (Karski, 1944; Piekałkiewicz, 2020). He had studied in Germany and Switzerland and had already travelled to France to brief the Government in Exile on conditions within Poland. Briefed by the President of the Delagatura, Jan Pielałkiewicz and members of the Jewish underground, Leon Feiner and Menachem Kirshenbaum, Karski carried a report on the annihilation of Jews up to September 1942 which made horrific reading (Karski, 1944; Ciechanowski, 2005; Kochanski, 2012; Piekałkiewicz, 2020) with the outcome of the ghetto uprising being confirmed by Jan Nowak (Nowak, 1982) when he reached London.

However, the initial reports into the mass killing of Poland’s Jewry was not believed (Ciechanowski, 2005) despite Karski meeting Eden on two separate occasions who was convinced the report to be accurate and contacted Lord Halifax in the USA. Lord Selborne refused Karski’s request for the Allies to intervene as he was more focussed on the AK’s strategic plans and uprising (Ciechanowski, 2005). Even Roosevelt deflected the conversation away from the fate of the Jews. In London, Cavendish-Bentinck reflected a wider opinion that reports through British Intelligence on the persecution and annihilation of the Jews was inflated by the Poles and Jews that in effect blocked these reports going to British decision makers and destroyed (Ciechanowski, 2005). By the time Nowak arrived in Britain with a more detailed report that included atrocities against the Poles and Jews, the scale of mass killings seemed to provoke almost contrary responses. Eden balked at Nowak’s suggestion in the bombing of rail networks leading to Auschwitz as the loss of aircrew and aircraft would not save the Jews, only a swift end to the war would, leaving Nowak bewildered. His report never made it to Churchill or Roosevelt and became a classified document long after the war’s end (Nowak, 1982; Ciechanowski, 2005).

As conditions in the ghettos deteriorated with scarcity in food and welfare, the Jewish Self-Help organisation under Dr. Michael Weichert provided primary source of relief that could not cover all the demands on their resources. Increased death rates and questions being raised over how aid was distributed (Gutman, 1994) placed the organisation in a quandary and was often seen as a rival to the Judenrat. Forced labourers were regularly beaten if the work detail quality or output did not meet Nazi demands which were based on unrealistic quotas given the level of depravation. By May 1942, most ghetto dwellers realised it was clear the Ghetto was a prison and the only relief, was the grave (Gutman, 1994).

Heydrich’s plans shifted towards the Endzeil (Final Plan) in the second half of 1941 which was in effect the Endlösung or Final Solution that became fully implemented from January 1942 (Kassov, 2007). With the Warsaw ghetto walled in apart from Chłodna Street that was within the ghetto, the main road was open with only a wooden fence separating the Jews from the ‘Aryan’ population. The access points or gates was reduced from 20 to 13 and then down to 4 with German, Polish and Jewish police manning them. The Jewish inhabitants became ingenious in survival with troughs being lifted to the walls so that bulk food could be delivered. The construction of a wooden bridge over Chłodna Street at the junction with Żelazna to help communication between the two parts of the ghetto. Tunnels were also dug to link the ghetto to residential areas outside the wall. The first was completed at the end of 1941 and ran from a ruined house on the corner of Gęsia and Okopowa streets and the second completed in July 1942 under St. Mary’s church and the monastery towards Lezno Street in the Polish quarter (Piekałkiewicz, 2020).

The Great Liquidation

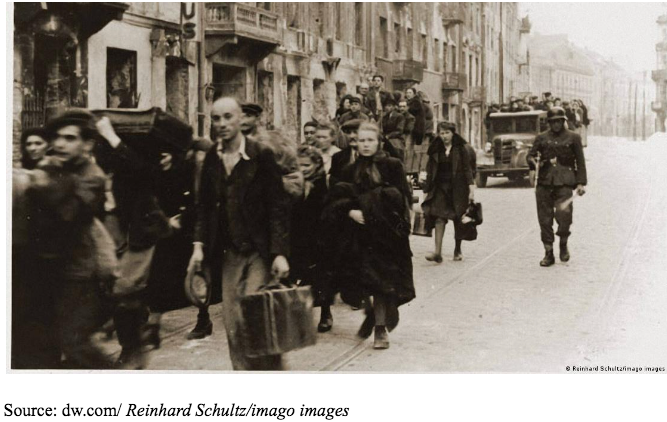

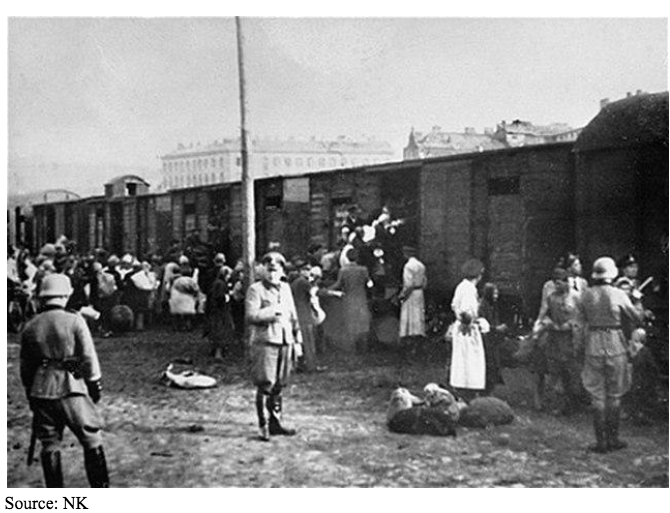

On 22nd July 1942 the ‘resettlement’ (the Great Liquidation Action, the Great Resettlement Action, or Great Deportation) of Jews to the east began and ended 24th September 1942 to the gas chambers at Treblinka. The head of the Judenrat, Adam Czerniaków, was informed that the deportations should commence due to the over-crowding and was ordered to inform the deportees they should take provisions for only three days and up to 15kg of hand luggage except for their valuables. People living in refugee centres, a boarding house on 3 Dzika Street and inmates from the Gęsia Street gaol were on the first transports. Jews were ‘corralled’ by barbed wire around Umschlagplatz and Stawki Street that became the loading area to Treblinka under Operation Reinhard (Witte and Tyas, 2001) and supervised by the Jewish Police. At night the special German Blue Police units made up of Lithuanian, Latvian and Ukrainian soldiers patrolled the boundaries of the ghetto. On the evening of 23rd July 1942 Adam Czerniaków was summoned to the offices of the Judenrat by the Germans with new orders for relocating inhabitants of the ghetto. On refusing to sign the order, he committed suicide when the Germans left. From 24th July onwards daily mass deportations began in earnest.

On 24th July 1942 all Poles working within the ghetto were banned from entering while the transports continued to empty the ghetto daily on the pretext of reducing the over-crowding with fear increasingly dominating daily life.

On 28th July 1942, representatives from pioneering youth movements met at the Dror hostel on Dzielna Street (Gutman, 1994). Representatives from Hashomer Hatzaír, Dror and Akiva formed ŻOB (Zydowska Organizacja Bojowa) indicated the youth movements had given up building a wider underground army (Gutman, 1994). Leading members of ŻOB were Yitzhak Zuckerman (Antek), Joseph Kaplan and Mordecai Tennenbaum-Tamarof who later left for Białystok and Mordecai Anielewicz who became leader of the group after lobbying other members to lead them (Dreifuss, 2017). Arieh Wilner (Jurek) was tasked to contact the Polish Secret Army (AK). Col. Stanisław Weber, Chief of Staff for the Warsaw District of the AK, maj. Jerzy Lewiński, chief of the AK’s sabotage branch (Kedyw) coordinated military action with ŻOB prior to the uprising (Zimmerman, 2017). Capt. Zbigniew Lewandowski ordered his snipers to shoot German sentries guarding the exists from the ghetto (Zimmerman, 2017) to destabilise and set fear amongst the German squads entering the ghetto. ŻOB’s sole aim was to defy the Germans and help preserve the identity and culture of Judaism. Through the act of ‘amidah’ dignity was restored against Nazi tyranny and oppression, with the Jewish Self-Help Committee providing much needed aid (Gutman, 1994).

False hope and subterfuge by the Gestapo through the ‘Hotel Polski Affair’ underlined both the subtlety and brutality of methods used by the Germans (Kassow, 2007; Piekałkiewicz, 2020). On 14th April 1942 citizens of the USA and Great Britain living in the ghetto were ordered to register with the authorities at about three months before the transports east started. Five days before the first transports east started, these passport holders were arrested and taken to Pawiak prison. It was assumed these passport holders were ‘lucky’ without knowing they would be transported to camps for foreigners in Tittmoning in Bavaria or Vittel in France (Fischel, 2006; Piekałkiewicz, 2020). Learning of this ‘special’ treatment many Jews with relatives abroad, mainly in Latin America made requests for foreign passports in the hope in providing their escape. The process was complicated, however Dr. Abraham Silberschein established the Relief Committee for the War Stricken Jewish Population in Bern and issued promesa which acted as a temporary passport. Other Jewish organizations such as Agudat Yisrael and financed by the World Jewish Congress, obtained the necessary documents from the consulates in Bern. It is estimated 2,500 Jews fell into the trap and entered the hotel in their bid to escape. Most were transported to concentration camps like Bergen-Belsen or executed in Pawiak prison (Kassow, 2007; Piekałkiewicz, 2020). The Gestapo made it known these documents could be purchased in the hotel (originally based in the Hotel Royal) with Leon Skosowski, Pawel Włodawski and a long-time Gestapo informer, actress Franciszka Mann fronting the operation (Grabowski, 2008; Piekałkiewicz, 2020) for the exchange of documents from Germans living in Latin America. These names were then put on the ‘Palestine List’ for emigration. Franciszka Mann’s role is controversial in the Hotel Polski Affair and was executed by the AK for treason.

The AK’s role in the Ghetto Uprising remains one of the most controversial topics in Polish-Jewish relations (Kassow, 2007; Zimmerman, 2019; Piekałkiewicz, 2020) that is exemplified by conflicting testimonies and experiences ranging from abuse through to being accepted as an equal into AK units (Piekałkiewicz, 2020) with Gen. Stefan Rowecki having progressive democratic views that rejected antisemitism (Zimmerman, 2019; Piekałkiewicz, 2020). Despite this, some local AK units mainly in eastern Poland, were hostile to Jewish partisan units hiding in the forests who had communist sympathies (Zimmerman, 2017; Zimmerman, 2019; Kochanski, 2012; Piekałkiewicz, 2020). Hostile AK units whose members had been recruited originally from the NSZ (Narodowe Siły Zbrojne), a right-wing party, were also accused of collaborating with the Nazis and Gestapo and indeed also fought them and the Soviets plus amongst themselves (Paczkowski, 2003; Kochanski, 2012). In contrast, Piekałkiewicz, (2020) suggested that the leader of the ONR (Obóz Narodowo-Radykalny) Jan Mosdorf, a semi-fascist party assisted Jews with food parcels whilst he was a prisoner in Auschwitz.

The AK also formed in 1942 a council for Aid to Jews, named Konrad Żegota Committee (Żegota or Rada Pomocy Żydom przy Delegaturze Rządu RP na Kraj) that gave aid to destitute Jews (Gutman, 1994; Kassov, 2007; Piekałkiewicz, 2020) whose role is often overlooked despite saving thousands of lives through funding and providing false documentation or hiding them within the local populous as Catholics (Paulsson, 2002; Golarz and Gorlaz, 2011, Piekałkiewicz, 2020). The new committee, headed by Henryk Wolinski (Wacław), a lawyer (Gutman, 1994) was recognised by the Government in Exile in London and was composed of representatives from all major political parties from occupied Poland (Piekałkiewicz, 2020). A presidium oversaw the management while the ‘Bureau’ covered the day to day running and provision of aid to the Jews mainly in hiding through its housing and children’s medical departments (Gutman, 1994; Kassov, 2007; Piekałkiewicz, 2020).

Alexander Kaminski (head of the AK’s Bureau of Information and Propaganda) championed the Jewish cause through his editorship of the Biuletyn Informacynj (Bulletin of Information) which was the main newspaper run by the AK. Under Kamiński’s editorship, the paper extensively covered the distress and fate of the Jews (Gutman, 1994; Zimmerman, 2017) and through his friendship with Irena Adomowicz (scout leader and resistance member), had access to Hashomer Hatzaír and to Dror organisations (Kassow, 2007). However, the Yediot, a paper run by the Dror did acknowledge the local Polish populous seemed to have ‘lost elementary feelings of humanity stand out all the more against this dark background’ (Kassov, 2007:375). These views were not held by Ringelblum, leader of the Aleynhilf whose notes and archives were buried in milk churns in the rubble of the ghetto before its final destruction where his estimates indicated about 15,000 Jews were in hiding in Poland between 1942 and 1943. These figures were revised up to 30,000 by Poulson (2002) and deemed by many to be a more accurate figure (Kassov, 2007).

On 1st August 1942 the Bund sent Załmen Frydrych (Zygmunt) on a hazardous journey to follow the transports to Treblinka and by 4th August 1942, underground leaflets warned of the real purpose of the ‘resettlement’ to the east.

On 9th August 1942 all Jews in the smaller ghetto south of Chłodna Street were ordered to leave their apartments by 18.00 the next day and the Judenrat moved from 26-28 Grzybowska Street to 19 Zamenhofa Street with a demand they provided 7,000 people for ‘resettlement’ the next day. On 10th August 1942 Dawid Nowodworski, a member of the Ha-Szomer ha-Cair, had escaped from Treblinka whose account provided concrete evidence and confirmed Załmen Frydrych’s witness account of the genocide (Kassow, 2007). On 15th August 1940, housing in Nowolipki, Nowolipie, Dzielna, Smocza, Pawia, Więzienna, Lubeckiego, Gęsia, Okopowa, Gliniana, Zamenhofa, Nalewki, Wałowa, Franciszkańska, and Mylna, Leszno were cleared with shops requisitioned for those producing goods for the Germans.

Around the 19-21st August 1942, transportations were temporarily suspended from the ghetto while the Germans emptied nearby local towns. By 25th August the mass deportations resumed with panic spreading across the ghetto. On 5th September 1940, a further section of the ghetto Smocza, Gęsia, Zamenhofa, Szczęśliwa, and Parysowski Square were to be cleared and the inhabitants to bring minimal belongings to survive their two-day transportation. The Germans subsequently focussed on limiting employment in the ghetto by introducing employment cards or metal plates known as “numbers of life” hoping this was a sign of deliverance for the 35,000 remaining in the ghetto (Gutman, 1994). Not even the celebration of Yom Kippur eased the transports with the SS announcing the ‘Great Liquidation transports’ had been completed by 24th July. Within the ghetto, shock, exhaustion, astonishment, anger, and revulsion impacted upon the thoughts and lives of the survivors (Gutman, 1994) which then opened questioning why there was no defence organisation to resist or oppose or even retaliate against the despised Jewish Police who were so complicit (Gutman, 1994, Kassov, 2007).

In November 1942, ŻOB (Zydowska Organizacja Bojowa) became more determined in seeking help from the >AK for weapons and on 2nd December 1942, they announced that if deportations continued, “Not a single Jew will go”. AK underground leaflets condemned the transports and treatment of the Jews demanding Poles desist in any involvement (Piekałkiewicz, 2020). Only after the great deportation ended did the Bund ask Leon Feiner (Mikolaj) to mediate with the AK and pass information onto Shmuel Zygelbojm, a member of the Polish National Council in London (Gutman, 1994; Karski, 1944; Piekałkiewicz, 2020). Controversy surrounds the degree of contact with the AK and the level of knowledge Gen. Tadeusz Komorowski, its deputy commander (Gutman, 1994) and the Government in Exile professed to know (Piekałkiewicz, 2020). Despite a press conference that had been held on 9th July 1942 with the request that the Bund’s report be published again in both Britain and the USA (Gutman, 1994; Piekałkiewicz, 2020) as an act of confirmation. Wolinski’s original report clearly showed no contact with the Jews had been established and contradicted Komorowski’s account despite AK internal reports indicating Wolinski had in fact met with Arieh Wilner (ŻOB) in the ghetto (Gutman, 1994). Only Karski’s report and visit to Britain in the autumn of 1942 would cement the Government in Exile and the Allies assurance of the mass killings to be true. More confusing was Stefan Rowecki’s (Grot) praise for ŻOB to fight. The limited contact and many obstacles put in place by the AK hindered ŻOB’s ability to fight against tyranny effectively. Although ‘Polish’ national-ethnic treated the Jews as social outsiders, despite centuries of settlement in Poland, there was no feeling in “universe of common obligation” that Helen Fein observed (Gutman, 1994). From a military stance, supplies and the logistics of arms and munitions was still limited and did not substantially cover the pressing needs of the AK’s plans for their insurrection (Gutman, 1994) (TNA HS4-140; TNA HS4-142; TNA HS4-143) with the ghetto uprising not being included in the AK’s plans (Paczkowski, 2003).

On 11th January 1943 intercepted radio messages between SS Lt. Colonel Eichmann at RSHA Berlin, and to SS Lt. Colonel Heim, deputy commander of the Security Police and SD for the General Government in Kraków from SS Maj. Höfle confirmed transports to Treblinka and other camps (TNA HW 16-23) cited by Witte and Tyas (2001) confirms the level of knowledge within British intelligence over the mass transports and the Wehrmacht complicity through a passive attitude (Tyas, 2008).

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

In January 1943, surviving ghetto inhabitants were required to labour in German enterprises and when the second expulsion or action against the Jews restarted on 18th January 1943 and lasted four days. Disbelief, gloom, and depression descended upon the ghetto (Gutman, 1994). Jewish resistance members hid the second part of the Ringelblum archive of documents in milk churns at Nowolipki 68 detailing the ghetto’s destruction (Kassow, 2007). Rumours surrounding the final liquidation of the ghetto circulated around Warsaw (Gutman, 1994).

19th April 1943 (Passover) two columns of German troops entered the central ghetto. The operation was led by Ferdinand von Sammern-Frankenegg, head of the SS and police units in Warsaw. He had led the first Grossaction or Great Liquidation Action and the uprising would prove to be his professional and political undoing as Himmler lost confidence in his ability to control the clearance of the ghetto (Gutman, 1994). Sammern-Frankenegg at first ‘redacted’ the level of resistance and was unaware of the scope of opposition (Gutman, 1994). The German units approached the intersection at Zamenhofa and Miła Streets with 33 Naleski Street and were surprised by the attack from ŻOB resistance units of under the command of Mordecai Anielewicz (Gutman, 1994; Paczkowski, 2003). Reinforcements were called up and the troops were supported by a tank and lighter armoured cars but suffered substantial losses and withdrew.

The second attack started at 0800 and now led by SS Brigadeführer Jürgen Stroop, a committed Nazi, pushed back the resistance fighters from Nalewki and Zamenhofa Streets. Stroop reported daily on the ghetto uprising, actions by the German troops and the transports to Treblinka or other camps.

After a brief lull, the Germans attacked the fortified locations in Muranowski Square held by the ŻZW (Żydowski Związek Wojskowy or Jewish Military Union) and commanded by Pawel Frenkel (Gutman, 1994; Piekałkiewicz, 2020). Casualties were relatively light on both sides and on the retreat of the Germans, many inhabitants descended into their pre-prepared bunkers. The German hold over the ghetto forced the resisters to fortify their bunkers and carrying out ‘sorties’ to help defend families within the ghetto (Gutman, 1994). Not all bunkers were of military significance but hiding places in the cellars and roof-spaces or attics to survive (Gat, 2009).

At 1900hrs a unit of the AK (Warsaw Kedyw) commanded by Captain Jozef Pszenny attempted to blow a hole in the ghetto wall (Zimmerman, 2017) at the corner of Bonifraterska and Sapieżyńska Street. Armed only with mines, local on-lookers made the action more treacherous and failed in their mission without the Jews knowing of the action (Gutman, 1994) which resulted in several casualties amongst the AK fighters.

On 20th April 1943 German action in the ghetto resumed at 0700hrs with fierce fighting around Muranowski Square that moved on towards Świętojerska Street with residents refusing to abandon their homes and bunkers within the district despite AA guns being brought in to demolish bunkers and render resistance useless. The defenders detonated explosives that halted the German attack temporarily while another German unit engaged ŻOB and ŻZW units nearby to the brush makers workshops.

On 21st April 1943 the Germans changed tactics. Smaller skirmishing units combed the buildings in the central area of the ghetto with orders from Jürgen Stroop to set fire to buildings. During the night, ŻOB units re-entered the central ghetto and reached the bunker at 30 Franciszkańska Street. Workers trapped between the resistance and Germans in the Többen’s and Schultz workshops were ‘evacuated’ by the Germans to the Umschlagplatz and finally deported to the labour camp at Poniatowa near Lublin.

22nd April 1943 a huge fire spread through Świętojerska, Franciszkańska, Wałowa and Nalewki Streets, and later Zamenhofa Street, forcing the resistance to move around the bunker complex within the ghetto to avoid the fires and the shelling with incendiary shells. Captured bunkers were blown up and resistance fighters executed. Many perished in the flames and those who tried to escape through the sewers were gassed. Over 1,000 Jews were rounded up and escorted to Umschlagplatz for deportation. Some fighters belonging to ŻZW escaped to the “Aryan side” near 6 Muranowska Street.

23rd April 1943, Jürgen Stroop systematically started to clear the ghetto with the support of additional assault troops who destroyed 48 bunkers and executed 200 people including members of the Bund. Any survivors were marched to Umschlagplatz awaiting transports east while small units of the AK were active around the walls of the ghetto.

On 24th April 1943, the Germans launched a surprise attack at 1000hrs from all sides where the resistance put up a fierce fight around Werterfassung warehouses in Niska and Pokorna Streets with German units systematically setting fire to buildings and shooting 330 people on the spot. Any survivors were marched to Umschlagplatz with some 1,800 rounded up.

SS Brigadeführer Jürgen Stroop was under pressure to complete operations’, and he promised by Easter Monday the insurrection would be over.

25th April 1943, at 1300hrs: Over 500 assault troops re-entered the ghetto and continued the systematic clearing and razing buildings or destroying bunkers, killing over 270 and 1,690 captured and subsequently transported to Treblinka. Attempts by ŻOB units to escape through the sewers failed and were killed through booby traps and gas.

26th April 1943, 1000hrs: German assault troops again entered the ghetto for ‘mopping’ up operations and met stiff resistance that was quickly suppressed with over 1,330 Jews killed in mass executions with more bunkers destroyed whose inhabitants were killed.

27th April 1943, German assault troops began to clear ghetto bunkers in the area around Niska Street and the level of German brutality increased with 550 prisoners executed out of 2,500 captured and those trapped in the bunkers perished where they were hiding according to Stroop’s report. By the evening, ŻZW fighters in the apartment buildings at 6 Muranowska Street were captured and most shot. Any survivors were transported to Majdanek.

28th April 1943: assault troops continued to clear sections of the ghetto and suppressed any resistance they encountered with 1,655 captured and 110 shot in combat conditions according to Stroop.

29th April 1943: Symcha Ratajzer and Zalman Friedrich escaped from the ghetto through a tunnel under Muranowska Street to meet resistance organisations on the ‘Aryan’ side to facilitate the escape of the Jewish underground fighters. Stroop’s report indicates 2,359 Jews were rounded up of which 106 were executed. The AK appeal to Varsovians to help the Jewish cause and refugees from the ghetto.

30th April 1943: assault troops were finding it increasingly more difficult to flush out the resistance fighters and although 30 bunkers were destroyed along with escape routes, the ingenuity of ŻZW and ŻOB units enabled resistance groups to escape through the sewers in Leszno Street or managed to escape to Michalin in the suburbs of Warsaw. Stroop reported 37,359 Jews had been captured and a further 3,855 were transported onto trains at Umschlagplatz.

1st May 1943 at 0900hrs, ten special combat units re-entered the ghetto and remained until 2200hrs blowing up or sealing sewers and bunkers to prevent any further escapes. Resistance fighters continued to engage the German troops making the operation hazardous. Stroop ordered the ‘Aryan’ side of Warsaw to be patrolled for escapees.

2nd May 1943, the ghetto operations are taken over by Friedrich Wilhelm Krüger, the Higher SS and Police Leader and a staunch Nazi, was shipped in from Kraków. Within the ghetto 24 more bunkers were discovered and any survivors taken to Umschlagplatz for transportation.

3rd May 1943: operations started at 0900hrs and still met resistance in the areas of 22 and 30 Franciszkańska Street, the hiding place of ŻOB combat groups. By this time, the shortage of food, water and ammunition was taking its toll on the fighters.

4th May 1943: clearing out stubborn resistance around the Többens and Schultz workshops continued with more building set ablaze to flush out those in hiding and an estimated 2,283 people were captured. At night, special scouting parties remained within the ghetto to locate and destroy any insurgents.

5th May 1943: deportations to labour camps of those recently captured begins with 1,070 people captured and herded towards the train wagons.

6th May 1943: assault troops re-swept the ruins seeking out any more survivors with an additional 47 bunkers located and destroyed. 1,553 people are captured with 356 executed on the spot. Stroop in an act of desperation, offered financial rewards for captured insurgents as the city was swept for escapees from the ghetto.

7th to 9th May 1943, operations within the ghetto continue with bunkers blown, sewers gassed, and remaining buildings set ablaze with captured people sent to Umschlagplatz for transportation. The shooting of prisoners continued unabated. Some resistance units were lucky in discovering tunnels and an opportunity to escape. Unfortunately, the ŻOB command bunker at 18 Miła Street had been surrounded by the SS through treason (Gutman, 1994). Despite a heroic fight, few escaped the gas being pumped into the basement complex with 60 captured and 140 executed. This was the turning point of the Uprising, and many chose suicide rather than capture (Paczkowski, 2003).

10th May 1943: Stroop reported that the will of the resistance was no weaker. At 0500hrs a combat group of 50 fighters emerged from the sewers at Prosta Street to an awaiting truck that took them to Łomianki in the Kampinos forest where they met up with other resistance fighters.

11th to 14th May 1943, the destruction of the ghetto continued with mass shootings and deportations. German propaganda indicated the level of frustration in liquidating the ghetto when they declared the Jews were responsible for the Katyń massacre to deflect any focus away from their own activities since the Katyń had only just been uncovered in April 1943.

15th May 1943, the German assault troops encounter few isolated Jews in the ruins and the remaining survivors used what weapons existed and ‘Molotov’ bombs as a final act of defiance. Any remaining buildings in the ghetto were destroyed.

16th May 1943, the destruction of the Warsaw synagogue on Tłomackie Street at 2015hrs was the last act in the destruction of the Warsaw ghetto. It was described by Stroop as a ‘marvelous sight’ and ended his mission to rid the city of Jews. Almost untouched by the Ghetto uprising, this impressive building was the last symbolic building representing the Jewish culture, religion and society that had been part of the fabric of Poland since 1097.

Aftermath

Despite unselfish acts of heroism, the doomed ghetto uprising shocked the Germans who were ill prepared for any form of resistance (Gutman, 1994). The dismissal of von Sammern-Frankenegg after the initial attack was as much about his failure, but also a need for the Nazis not to be distracted at this juncture of the war since gains in North Africa and Soviet advances into the Ukraine had hardened Germany’s resolve in maintaining the Reich.

von Sammern-Frankenegg was court-martialled by SS leader Heinrich Himmler on 24th April 1943 for his ineptitude and weakness in handling the Jewish uprising that was an embarrassment to the Nazis. Posted to Serbia, he was killed in action against Yugoslav partisans near Klašnić.

Friedrich Wilhelm Krüger had an extensive military ‘career’ that focused on wholesale ‘ethnic cleansing’ and was responsible for the annihilation of approximately 3m Poles and 3m Jews. His despicable activities included suppressing any uprisings or rebellions in the camps. In Aktion Zamosc, Krüger led the annihilation of 116,000 Poles and many were children. Those with Aryan features were sent to Germany to be Germanized with some finally returning to Poland after the war was over. Disagreements with Hans Frank, the Governor General of Poland in November 1943 saw his dismissal and re-allocation of duties. The AK ordered his assassination and the attempt on his life in Kraków on 20th April 1943 failed. From November 1943 until April 1944, he served with the SS Division Prinz Eugen engaged in anti-partisan guerrilla warfare in Yugoslavia then moved to the SS Division Nord on the Finnish border before transfer to the Army Group Ostmark in May 1945 after a short posting to the V SS Mountain Corps. He avoided the Nuremberg trials and retribution through committing suicide in Austria before he could be captured and escaped the gallows.

SS Brigadeführer Jürgen Stroop’s account of the ‘liquidation’ in his infamous report became the basis for his indictment for the crimes he committed. Rather than hide his heinous crimes, the photographic evidence provided confirmation of his guilt, and these became iconic images of the tragic genocide (Gutman, 1994). He was initially prosecuted at the Dachau Military Tribunal and convicted of murdering nine U.S POWs and then extradited to Poland for crimes against humanity. His execution in Mokotów Prison in Warsaw on 6th March 1952 was a ‘fitting end’ to an arrogant Nazi who showed no remorse for the genocide he participated in.

The International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg 1945-1946 presented issues with how to represent the Jews both as individual survivors and organisations (Jockusch, 2012) since many Jews were displaced people spread across Europe and into the Balkans. While leading Nazis from the military, political and economic sections of the Reich stood trial, Holocaust trials were fewer and focussed on the role of the Einsatzgruppen whose plea of ‘following orders’ still rings hollow to this day since it ignores any humanitarian, ethical or moral concepts. Those who eluded capture and trial were relentlessly hunted by war crimes investigators and the Simon Wiesenthal Centre. The Allies were ambitious and prosecuted 1,500 Nazi war crimes that acted as both a deterrent for future acts of genocide, and punishment to Germany for its role while at the same time educating the populous of their collective responsibility. Hundreds of Germans were convicted of their crimes, however the Cold War presented challenges to post-war Europe where in 1955 3,300 former Nazis were released from prison. Releasing prisoners placed pressure on Russia to release former soldiers from prisons and the Gulags thus making de-Nazification more complex.

Dealing with war crimes and crimes against humanity was made multifarious due to the Soviet bloc in post war Europe, particularly in Poland (and other central European countries) where there was immediate chaos and uncertainty after the collapse of the Reich and Soviet occupation. The communist backed governments sought recognition and legitimacy (despite rigged elections), shrouded the judicial process until the collapse of communism in 1989 (Gulińska-Jurgiel, 2019) making any analysis and comparison to the Allies prosecutions or restitution difficult.

While compensation was paid to survivors, restitution of Holocaust looted art was not prioritised (O’Donnell, 2011) which left a sense of ‘unfinished business for many years that slowed reconciliation and atonement within the process of transitional justice. ‘Cold comfort’ for the surviving Jewish diaspora, however restitution represents the final stage in the Holocaust’s legal reckoning and should not necessarily be linked to or confused with responsibility (O’Donnell, 2011).

Summary Of Other Jewish Uprisings 1941-1944:

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was not an isolated action of defiance and resistance towards the Nazi regime. In five major cities and forty-five provincial towns affirmative actions’ took place with varying degrees of success and ended mostly failures:

|

29th June 1942

|

Słonin Ghetto, (now Belarus)

|

Local revolt against the Nazis with 5 Germans killed. The ghetto was emptied by August 1942 with between 8,000-55,000 Jews annihilated. A few escaped to the forests and partisan units.

|

|

3rd September 1942

|

Łachwa (now Lakhva, Belarus)

|

Knowing other ghettos were being liquidated by the Nazis, the order to be ‘resettled’ triggered the uprising. 650 Jews killed in the fighting with about another 500 taken to execution pits. Some 600 escaped into the Pripet marshes with approximately another 120 joining Soviet backed partisans.

|

|

14th October 1942

|

Mizocz Ghetto, (now in the Ukraine)

|

12th October 1942 the ghetto was sealed with 1,700 Jews to be liquidated. The residents set fire to the ghetto with several hundred escaping with many captured and shot in a local ravine.

|

|

10th January 1943

|

Mińsk Mazowiecki Ghetto (now in Belarus)

|

In August 1942 about 7,000 Jews had been sent to Treblinka. On 10th January 1943 250 remaining slave labourers were shot in the street following the prisoner’s revolt.

|

|

25th June 1943

|

Częstochowa, Poland

|

The clearing of the ghetto caused an uprising with 1,500 Jews killed and on 30th June a further 500 perished in the burning down of the ghetto. 3,900 Jews had been rounded up and sent to work camps followed by a further 10,000 Jews being transported from Skarżysko-Kamienna in 1944 ahead of the Soviet advances.

|

|

2nd August 1943

|

Treblinka

|

When some of the German and Ukrainian camp guards left for a swim in the nearby River Bug, the arsenal was opened with duplicate keys with arms and grenades. The insurrection initially lasted 30 minutes with buildings set ablaze and the attempt to storm the main gates or climb over the wire was met with heavy machine gun fire with heavy losses. About 200 escaped and were hunted down with about 70 surviving in the forests. The camp commanders were dismissed and sent on anti-partisan actions. Treblinka was closed down as Auschwitz had capacity to fulfill Operation REINHARD.

|

|

3rd August 1943

|

Będzin – Sosnowiec Ghetto in the Dąbrowa Basin, southern Poland.

|

The round ups and deportations were from June to August 1943 to Auschwitz with approximately 30,000 held in the ghetto.

ŻOB organised the uprising principally led by Cwi Brandes, Frumka Płotnicka and the Kożuch brothers. Over 400 fighters were killed. The local convent led by Teresa Janina Kierocińska rescued and hid some surviving Jews as did other members of the Polish community.

|

|

16th August 1943

|

Białystok Ghetto Uprising

|

This was the second largest insurrection led by Mordecai Tennenbaum-Tamarof who had witnessed the terror within the Warsaw ghetto and Daniel Moszkowicz (Dawid Chone/ Jerzy). Armed with a machine gun, some rifles, and a few pistols with Molotov petrol bombs to attack armoured columns. The situation was hopeless and the fighters chose to die with dignity. Isolated pockets of resistance lasted a few days, however the SS set fire to the ghetto and the deportation of approximately 10,000 Jews recommenced on 17th August to Treblinka, Majdanek and Auschwitz. Some resistors escaped to the surrounding forests and joined the AK. The Uprising leaders committed suicide in their bunker when they ran out of ammunition.

|

|

7th October 1944

|

Auschwitz-Birkenau, Oświęcim,

|

Prisoners assigned to crematorium IV mutinied after learning of their impending death. There was an underground movement within the camp set up by the AK in 1942 and the revolt was led by Załmen Gradowski and Józef Deresiński who died in the action. Explosives from the Union-Werke armaments factory had been smuggled into the camp and was used by the Sonderkommando in destroying one of the crematoria and attacked SS guards. Prisoners cut the camp wire and temporarily escaping only to be shot. The women who had smuggled the explosives were publicly hung. The Germans suffered minor injuries and three men killed. 250 Jews perished in the revolt.

|

|

14th October 1943

|

Sobibór, Żłobek Duży in the Lublin Voivodeship.

|

Sobibór was the fourth largest extermination camp in today’s eastern Poland. The design of the camp differed from others to disguise its purpose.

The original plan consisted of two phases with the detail being handled by the co-organiser Leon Feldhendler. In the first phase SS officers would be lured to secluded locations around the camp and killed. The second phase would begin at evening rollcall with the Kapos ordering a special detail to work in the forest and allow the prisoners to walk to freedom.

Led by Alexander Pechersky, the assassination of the commandant Reichleitner was prioritized, however during the revolt was on leave. The Deputy Commandant SS Untersturmführer Johann Niemann entered the camp on horseback for a leather jacket to be fitted which gave the conspirators to assassinate him with an axe. The execution of SS guards in various locations commenced with some improvisations when the plan drifted. As the bugler announced the end of the working day and rollcall, prisoners hurriedly assembled in the Lagers with some confusion over what was happening.

Pechersky announced the revolt had started and amongst the confusion remaining guards though the camp was under attack by partisans.

With seized weapons, the prisoners opened fire with some scaling the wire from secreted ladders near the carpentry workshop and stormed the main gates despite being shot at. Many escapees attempted to scale the wire and became entangled while others attempted to cross a minefield.

Some 300 made it to the forest and the partisans where they hid. Approximately 158 inmates perished inside the camp with a further 107 tracked down and killed before getting away.

Although there was confusion, reinforcements from Chełm prison assisted in sweeping up pockets of resistance within the camp and those hiding in local villages.

The threat of advancing Soviet units and the need to hide the atrocities saw the camp closed and remaining inmates sent to Treblinka.

|

Further Reading

Anon(2012) “A Brief History of the Holocaust”, Montreal Holocaust Memorial Centre, Canada.

Arendt, H. 1977 “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil”, Penguin re-print in 2006, UK.

Bilsky, L. (2001) “The Arendt Controversy 2000: An Israeli Perspective”, HannahArendt.net in“50 Years of “The Origins of Totalitarianism””, Vol.5 No.1, pp. 41-46

Brustein, W.I. (2011) “European antisemitism of Europe and roots of Nazism” in ““The Routledge History of the Holocaust”, Socialism and Democracy, Friedman, J.C. Ed, Routledge, UK. pp. 18-29.

Brustein, W.I. and King, R.D. (2004) “Anti-Semitism in Europe Before the Holocaust”, International Political Science Review, Vol.25, No.1, pp.35-53.

Ciechanowski, J. (2005) “SOE and Polish Aspirations”,Intelligence Co-Operation Between Poland and Great Britain During World War II”, The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee, Vol. 1, pp.535-546.

Davies, N. (2007) “Rising’ 44: The Battle for Warsaw” Pan Macmillan, UK.

Dreifuss, H. (2017) “The leadership of the Jewish Combat Organization during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising: A ReassessmDreifuss, H. (2017) ent”,Holocaust and Genocide Studies,Nol. 31, No. 1, pp.24-60.

Ezra, M. (2007) “The Eichmann Polemics: Hannah Arendt and Her Critics”,DemocratiyaSummer, pp. 141-165.

Fairweather, J. (2019) “The VoluntFairweather, J. (2019) eer: The true story of the resistance hero who infiltrated Auschwitz” Penguin Random House, UK.

Fischel, J. (2006) “Secret City: The Hidden Jews of Warsaw 1940-1945: A review”, An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies Vol.24, No. 2, pp. 184-186.

Friling, T. (2006) “Istanbul 1942-1945: The Kollek-Avriel and Berman-Ofner Networks”, Secret Intelligence and the Holocaust, ed. by David Bankier, Enigma Books, pp. 105-156.

Gablenz, N.G. (2020) “(Un) Ethical (In) Action: Judenrat Leaders and Hannah Arendt’s Fine Line between Resistance and Complicity”, SUNY, The State University of New York at Buffalo, USA, pp.1-30.

Gat, E. (2009) “Not Just Another Holocaust Book”, I.C.L, Israel.

Gorlaz, R.J and Gorlat, M.J. (2011) “Sweet Land of Liberty”,AuthorHouse, USA. See page 94.

Grabowski, J. (2008) “Szantażowanie Żydów: casus Warszawy 1939-1945”, Przegląd Historyczny, Vol.99, No.4, pp.583-602.

Gulińska-Jurgiel, P. (2019) “Post-War Reckonings: Political Justice and Transitional Justice Theory in the Theory and Practice of the Main Commission for Investigation of German Crimes in Poland in 1945”, in “Political and Transitional Justice in Germany, Poland and the Soviet Union from the 1930s to the 1950s” Brechtken,M; Bułhak, W; and Zarusky, J, Wallstein Verlag, Germany.

Gutman, I. (1994) “Resistance: The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising”Mariner Book, USA

Hammel, A. (2020) “Child Refugees Forever? The History of the Kindertransport to Britain 1938-1938”, Diskurs Kindheits- und Jugendforschung Heft, Vol.2, pp.131-143.

Jockusch, L. (2012) “Justice at Nuremberg? Jewish Responses to Nazi War-Crime Trials in Allied-Occupied Germany”, Jewish Social Studies,Vol.19, No.1, pp. 107-147.

Karski, J. (1944) “Story of a Secret State: My report to the World”, Penguin Random House, UK (Reprint).

Kassow, S.D. (2007) Who Will Write Our History?”,Penguin Books, UK.

Keskin Yilmaz, Y; Çaki, C and Kazaz, A. (2020) “Nazi Almanya’sı Döneminde Nazizm İdeolojisindeki Antisemitist Propaganda Mitlerinin Eğitime Yansıması”,Selçuk Iletişim Dergisi, Vo.13, No.3, pp. 1081-1113.

Kochanski, H. (2012) The Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War”, Allen Lane, UK.

Lederman, S. (2013) “History of a Misunderstanding: 'The Banality of Evil' and Holocaust Historiography”,Yad Vashem Studies,No.41, pp. 173-209.

Nowak, J. (1982) “Courier from Warsaw”,Wayne State University Press, USA.

O’Donnell, T. (2011) “The Restitution of Holocaust Looted Art and Transitional Justice: The Perfect Storm or the Raft of the Medusa?”,The European Journal of International Law, Vol.22, No.1, pp. 49-80.

Paulsson, G.S. (2002) “Secret City: The Hidden Jews of Warsaw, 1940-1945”, Yale University Press, USA.

Piekałkiewicz, J. (2020) “Dance with Death: A Holistic View of Saving Polish Jews during the Holocaust”, Hamilton Books, UK.

Tyas, S. (2008) “Allied Intelligence Agencies and the Holocaust: Information Acquired from German Prisoners of War”, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Vol. 22, No.1, pp. 1-24.

Witte, P. and Tyas, S. (2001) “A New Document on the Deportation and Murder of Jews during "Einsatz Reinhardt" 1942”, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Vol. 15, No.3, pp. 468-486.

Zimmerman, J.D. (2017) “The Polish Underground Home Army and the Jews, 1939-1945”, Cambridge University Press, UK.

Zimmerman, J.D. (2019) “The Polish Underground Home Army (AK) and the Jews: What Post-war Jewish Testimonies and Wartime Documents Reveal”, Conceptualizations of the Holocaust in Germany, Lithuania, Poland, and Ukraine since the 1990s, edited by Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe, Sage Publications, UK.

Additional Useful Resources:

Ambrosewicz-Jacobs, J. (Ed) (2009) “The Holocaust – Voices of Scholars”, Centre for Holocaust Studies, Jagiellonian University and the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum, Poland.

Edelheit, A.J and Edelheit, H. (2021) “Bibliography on Holocaust Literature: Supplement”, Routledge, UK.

Friedman, J.C (Ed) (2011) “The Routledge History of the Holocaust”, Routledge, UK.

Gudehus, C et al, (2018) “Revisiting the Life and Work of Raphaël Lemkin”, Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal, Vol.13, Issue1, Article 2, pp.1-204.

Jambrek, P. (2008) “EUROPEAN Public Hearing on Crimes Committed by Totalitarian Regimes”, The Secretariat-General of the Government of the Republic of Slovenia, Brussels.

Henry, P. (2014) “Jewish Resistance Against the Nazis”, Catholic University of America Press, USA.

Websites:

https://www.jewishpartisans.org/what-is-a-jewish-partisan

https://www.yadvashem.org/odot_pdf/Microsoft%20Word%20-%205704.pdf

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jewish-partisans-what-is-a-jewish-partisan

https://wienerholocaustlibrary.org/exhibition/jewish-resistance-to-the-holocaust/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/new-holocaust-exhibition-tells-jewish-resistance-inside-180975486/

https://www.haaretz.com/jewish/2014-01-13/ty-article/.premium/fiction-of-warsaw-ghetto-bunkers/0000017f-e577-da9b-a1ff-ed7f42bd0000

https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/jewish-women-partisans

https://www.ajc.org/news/podcast/x-troop-the-inspiring-untold-story-of-jewish-resistance-during-wwii

https://www.polin.pl/en/the-treblinka-uprising

https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/altman-tosia

https://sztetl.org.pl/en/towns/w/18-warsaw/116-sites-of-martyrdom/52425-anielewiczs-bunker-mila-street

https://www.jhi.pl/en/articles/may-8-1943-death-of-mordechai-anielewicz,616

https://ipn.gov.pl/en/news/6781,The-Stroop-Report-its-background-significance-and-whereabouts.html

(Stroops Official Report).

http://1943.pl/en/artykul/not-all-roads-led-to-hotel-polski/

Selected Fiction:

Andrzejewski, J. (2007) “Holy Week: A novel of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising” (Wielki Tydzien) (First published 1964) Ohio University Press, USA.

Hersey, J. (1954) The Wall”, Pocket Books, USA.

Uris, L. (1983) “Mila 18”, Bantam Books, UK – classic read.

Kubert, J. (2003) “Yossel: April 19, 1943”, IBooks, USA.

Gildin, L.H (2009) “The Polski Affair”, Diamond River Books, Canada.

Shepard, J. (2015) “The Book of Aron”, Penguin Random House, UK.

Safier, D. (2020) “28 Days: A novel of resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto”, Feiwel & Friends/ Macmillan, USA (aimed at children/ teens).

Notable Filmography:

‘Border Street’ (Ulica Graniczna in Polish) (1948) Directed by Aleksander Ford with Mieczyslawa Cwiklinska, Jerzy Leszczynski, Wladyslaw Godik and Władyslaw Walter.

‘Samson’ (1961) Directed by Andrzej Wajda with Serge Merlin, Alina Janowska and Elzbieta Kepinska.

‘The Wall’ (1982) Directed by Robert Markowitz with Tom Conti, Kisa Eichorn, Gerald Hiken and Rachel Roberts.

‘Korczak’ (1990) Directed by Andrzej Wajda with Wojciech Pszoniak, Ewa Dałkowska, Teresa Budzisz-Krzyżanowska, Marzena Trybała, Piotr Kozlowski, Zbigniew Zamachowski and Jan Peszek.

‘Son of Saul’ (2015) Directed by László Nemes with Géza Röhrig, Levente Molnár, and Urs Rechn.

‘The Zookeeper’s Wife’ (2017) Directed by Niki Caro with Jeff Abberley, Jamie Patricof, Diane Miller Levin, Kim Zubick, and Robbie Tollin.

‘The Pianist” (2002) Directed by Roman Polanski with Adrien Brody, Thomas Kretschmann, Frank Finlay, Maureen Lipman, Emilia Fox, Ed Stoppard, Julia Rayner, and Jessica Kate Meyer

Sobibór (2018) Directed by Konstantin Khabenskiy with Konstantin Khabenskiy, Christopher Lambert, and Felice Jankell.

‘Train of Life’ (1998) Directed by Radu Mihăileanu with Lionel Abelanski, Rufus, and Agathe de la Fontaine.

‘The Grey Zone’ (2001) Directed by Tim Blake Nelson with David Arquette, Steve Buscemi, Harvey Keitel, Mira Sorvino, Allen Corduner, Daniel Benzali, and Natasha Lyonne.

‘Run Boy Run’ (2013) Directed by Pepe Danquart with Andrzej Tkacz, Kamil Tkacz and Zbigniew Zamachowski.

‘Defiance’ (2008) Directed by Edward Zwick with Daniel Craig, Live Schreiber, Jamie Bell, Alexa Davalos, Allan Corduner, and Mark Feuerstein.

Hotel Polski (2009) Directed by Kama Veymont with Andrzej Adamczak. Cast not recorded.

‘Four Winters’, documentary https://www.jewishpartisansfilm.com

Selected Youtube.com resources:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8GzV4Tbfhuo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TC2wsXvDzCA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fjVQgDhMuis

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=12JvvGFs68g

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLj1tRCohZq80k-Y_6ml4-As2amr9AM8uJ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qhlwy6d8vBk

© Copyright polandinexile.com 2022. All rights reserved.

Site hosting by Paston.

|